Feelings of Inertia and Dread

Niamh Cullen

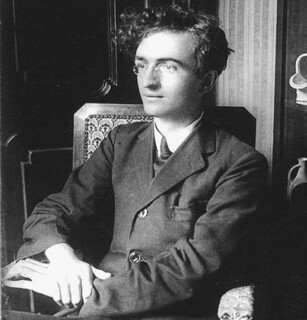

When I began to research my book on Piero Gobetti, the precocious young anti-fascist journalist and early victim of Mussolini, the world in which he lived seemed very remote to me. I could relate little of the post-1918 anger and desperation – the obsession with borders and national grievance, the struggle to make ends meet in times of unemployment and rising inflation, the angry men convinced they had been dispossessed – to my own circumstances. It was Dublin in the mid-2000s and the city was still feeling pretty boomy, with little hint of the global recession to come. The ideas and institutions of the EU seemed broadly secure and democracy was taken for granted. Now with the rise of populism and nationalism across Europe and the US, as responses both to the global recession and to the migration crisis, the anxiety, anger and fear of the 1920s and 1930s seem a little more real.

The trickier question is not why some people, out of desperation and anger, might have been drawn to Mussolini’s rhetoric, but why a more moderate and complacent majority allowed fascist fantasies to become reality. In teaching the history of fascism, I’ve found that there is a tendency to assume that the Italians were either brainwashed by propaganda into supporting Mussolini, or must have been secretly all anti-fascist. The truth must be both more complex and more mundane: the failure to resist was made up of hundreds of small accommodations and mental adjustments that allowed people to carry on almost as before. When Mussolini demanded that all Italian university professors take an oath of loyalty to the regime in 1929, only 12 refused.

Gobetti spent the last few years of his life trying to shock people into recognising that the new normality towards which the nation was drifting was anything but normal. In one of his bitterest articles, ‘In Praise of the Guillotine’, he called for fascism to become even more violent so that people might see what it really was. In fact, fascism became less overtly violent in its middle years, as Mussolini – not quite the buffoon that even Gobetti seemed to take him for at times – shaped the uncontrolled violence of fascism’s early phase into something more acceptable to a largely moderate public, before he plunged the country into war in the mid-1930s. Gobetti died in a Paris hotel in 1926, months after being assaulted by fascist paramilitaries.

I feel as if I now have a little more insight into how it might feel to see the ideas and institutions of the state collapse around you, and yet still go about your life as if nothing much has changed. In the last several years, with the rise of right-wing populism in Europe, Brexit, the migration crisis and the increasingly palpable effects of climate change, the world has profoundly shifted on its axis. Yet I have done little about it. I imagine these feelings of inertia and dread – the conviction that something should be done to prevent this downward slide combined with the strong sense that I can do nothing – is what it might have been like to live through the normalisation of fascism in Italy in the 1920s. This is not to suggest that Johnson, Trump et al. are similar to Mussolini – they may be, but that is a whole different issue – but rather that the sense of crisis that people lived with in the 1920s has parallels to our own time, as the extreme becomes normal, and it becomes gradually more difficult to imagine how things could be different.

Comments

That yet another detail between then and now. Natural allies to populist demagogues -- and that's the only way to describe them -- are split over the latest international bogeyman: immigration.