At the House of European History

Daniel Trilling

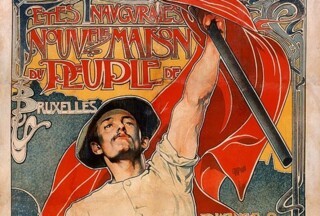

At the House of European History in Brussels, a long display cabinet sets out the forces that have shaped Europe through the centuries: philosophy, democracy, rule of law, ‘omnipresence of Christianity’, state terror, the slave trade, colonialism, humanism, the Enlightenment, revolutions, capitalism, Marxism, the nation state. For each, a historical image is matched with something contemporary: for philosophy, you get a bust of Socrates and a photograph of Žižek; for revolutions, Liberty Leading the People and the uprising in Kiev’s Maidan Square; for the slave trade, iron shackles and a Banksy painting about child labour.

The museum, which opened in 2017 at a cost of around €50 million, is the EU’s official attempt to tell the history of Europe since 1789. As might be expected, it treads a careful path, trying to craft a narrative of progress while balancing several competing demands: the national histories of 28 member states, rival political and economic ideologies – and, trickiest of all, the need to acknowledge episodes of mass violence without making anybody feel as if they are being unfairly blamed.

By and large, the museum does this by focusing on big, abstract concepts, or the different ways events are remembered and interpreted. When it works, it works well. The section on the Holocaust invites visitors to consider how it has been commemorated (or not) in West Germany, East Germany, Austria, France, Poland and the USSR. When it’s less successful, the approach works against understanding. A section on the industrial revolution – 19th-century paintings of Belgian factory workers and bourgeoisie face off against one another – is followed by one on imperialism: ‘Notions of progress and superiority’. The latter tells us about racist ideology and the way it underpinned colonial expansion, but not how any of that relates to the industrial revolution. Were the people forced to dig out the raw materials that fed European factories not workers too?

The museum has, inevitably, come in for criticism. The Daily Mail complained that it fails to acknowledge British achievements and doesn’t have enough about Brexit. (A small cabinet at the end of the route, entitled ‘appraisal and criticism’, shows a few campaign leaflets from the 2016 referendum.) People campaigning for communism and fascism to be treated as equivalent historic evils – they’ve managed to get politicians to mark a ‘European Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism’ in August – accused the museum of portraying the former Eastern Bloc too favourably. Though from what I could see, the main point here was to show that European unity was in part an attempt to create space between Moscow and Washington.

On its opening, a Ukip MEP described the museum as a metaphor for the EU: ‘The public never asked for it, it’s cost far more than we were originally told, the money is being spent on self-serving propaganda, and British citizens are expected to pay for it.’ If we’re looking for metaphors, a better one can be found in the building itself: a 19th-century bourgeois edifice whose insides have been stripped and replaced with the airy glass and steel architecture of a 21st-century office block; an institution caught between the language of 19th-century nationalism and smooth-talking global capital. The museum is an example of the weird vacuum you get when you try to avoid ideology.

A few steps away, giant banners hang above the main entrance to the European Parliament. They, too, are trying to say something about Europe, and are evidently intended to celebrate democracy: ‘In free and fair elections,’ one of them says, ‘the power of the people determines the people in power.’ They all carry the hashtag ‘#elected’ at the bottom, and reflect the priorities of voters (as recorded by a Eurobarometer poll). But they come across less as a picture of deliberation and debate than as a series of inflexible demands. Among messages about consumer protection, the environment and social rights, there are giant pictures of fighter jets, and patrol boats in the Mediterranean. ‘On May 23-25,’ one says, ‘42 million Europeans voted because they wanted to see Parliament take action to secure our borders. #elected’