Like wearing a raincoat when it rains

Alex Abramovich

Chicago’s Black Monument Ensemble started to form in summer 2014, after Michael Brown was killed by police in Ferguson, Missouri. Damon Locks was teachingart at a prison in Illinois, and feeling less than hopeful, when he heard the Pointer Sisters’ cover of Lee Dorsey’s ‘Yes We Can Can’ come over the radio. Locks had trained as a visual artist in Manhattan and Chicago and performed, for much of the 1990s, as the singer in a post-punk band called Trenchmouth. But the music that he began making now sounded nothing like punk. Inspired by Public Enemy, by that Pointer Sisters recording, by Archie Shepp’s Attica Blues, Phil Cohran’s Artistic Heritage Ensemble, Eddie Gale’s Black Rhythm Happening, and by a performance the Voices of East Harlem gave at Sing Sing in 1972, Locks started to layer beats over snippets of Civil Rights era speeches.

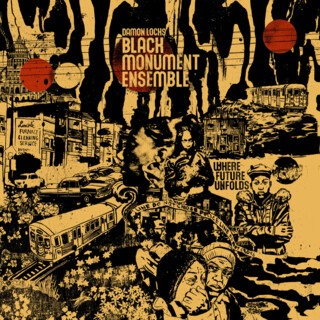

In 2015, he began to perform in public as a solo artist. By autumn 2017, the project had its name, and Locks had brought several collaborators on board. By the time of the concert they gave last November at the Garfield Park Botanical Conservatory in Chicago, the Black Monument Ensemble included Angel Bat Dawid on clarinet, Dana Hall and Arif Smith on percussion, graduates of the Chicago Children’s Choir, and members of the Move Me Soul youth dance company. The recording of the concert, Where the Future Unfolds, was released in May.

‘I can rebuild a nation,’ the Ensemble’s youngest member, Rayna Golding, sings midway through the performance. ‘I can rebuild a nation/no longer working out.’ Words don’t get simpler than that; and sung by a child, with conviction, they have power.

‘I’m not a lecturer, I’m not a writer,’ Lena Horne says in a recording Locks sampled for his composition ‘The Colours that You Bring’: ‘I guess I’m a performer. But I feel creative. I feel I need to be around people. I like it now. And I don’t know what I’m gonna do, but I’m not gonna stop.’

‘I don’t really remember how much rehearsal went into the performance,’ Locks told me the other day, over email. I was curious to know how a project like this came together, how improvised it had been, and how Locks had managed to make the old forms match up so neatly with the current moment. ‘A lion’s share of the songs were originally structured around samples and drum machines,’ he said.

For some songs those frameworks stayed and for some once the live drums and percussion were added I let them carry that structure and just added on top. We rehearsed in real time with instrumentalists (myself, Smith, Hall, and Angel Bat Dawid) and at least one singer (Phillip Armstrong) who would take it back and work with the singers. As we drew closer to the performance, most of the singers were at rehearsal … The dancers worked from recordings until the night before the show when we had everyone on hand to work out everything together.

We had been building up to this … We were building up and out, but the Garfield Park performance was the culmination of the work to date. There were some personnel changes to keep me on my toes … But once you are on stage, whatever happens is what the song needs.

If I hadn’t organised the ending for something, everyone had to listen to each other to figure out how to end … The dancers had much more room for improvisation. They had a lot of their parts worked out ahead of time but when the song happens and there are solos or the grooves go on longer or shorter than expected, they have to respond in kind.

‘Did the concert go as expected?’

Better. I had no idea what effect it would have. I mean, previous performances received the material wonderfully so I was hopeful. This was the first time with the instrumentalists, vocalists, and dancers with costumes etc. It was a big production. But the show was electric. The energy was palpable.

I didn’t know how to ask my next question. I could hear the connections to Attica Blues and other records Locks had referred to. And the reason I’d listened to his album so many times, and liked it more with each listen, was that returning to this deep well of vocal-oriented 1970s music (and on the deep wells that music had drawn on, in turn), seemed such a wise response to our current state of affairs: a way of seeing both music history and political history as a continuum, rather than a series of discreet episodes. I had just interviewed Swamp Dogg, an old guy using newish technology to address things that were happening in 2018. And I wanted to know more about a youngish guy who was breathing new life into old idioms, in response to the same things. But that wasn’t really a question. I ended up asking: ‘How old are you?’

‘I turned fifty right before we did this performance,’ Locks said.

Rayna Golding was seven. Everyone else was in between those ages. And it’s true that I consciously wanted to use the vocal group as a mode, inspired by groups like the Freedom Singers. That is an old form. In many ways I think of it as timeless. It is foundational. I really wanted to foreground voice, drums and dance. I didn’t really think of whether something was old or not. Old is so relative. Now Missy Elliot is old music to the teenagers I work with. I thought more about the political/social climate and how Black people responded in the arts and activism. I thought of its relationship to now. I was curious to use that form now and see what would happen? Would it resonate because it seems to fit the climate? Like wearing a raincoat when it rains. And I was interested in including more contemporary instrumentation – drum machines, synths, and samples – because those tools are the ones that this idea grew out of. It creates an artistic challenge, to meld these things. But I had no template for that.

Template; tool; weapon. ‘I try, I try, I still believe in us,’ the choir sings in ‘The Colours that You Bring’. ‘I still believe the break of dawn still cares.’ That belief, too, is simple and powerful, however far away the break of dawn may be, and however uncertain the morning that will follow.

Comments