Who killed Maurice Audin?

Jeremy Harding

Last week Emmanuel Macron issued a declaration acknowledging the role of the French military in the murder of a pro-independence activist in Algeria sixty years ago. The lead story in France should have been Macron's plan to break the chain of hereditary poverty with an additional €8.5 billion for children destined for a life of hardship bordering on misery. Arguments about the sums (insufficient) and the targeting (contentious) were quickly relegated to the sidebar as editors took the measure of Macron's conscientious, damning remarks on torture and disappearance during the Algerian war, a period that still clouds French sensitivities on inward migration, secular dress codes and acts of violence committed by radical Islamists.

It is common knowledge that the French tortured and murdered during the Algerian war (1954-62). The use of torture became a scandal in 1958, when the pro-independence communist Henri Alleg published La Question, an account of his interrogation at the hands of French paratroopers – electricity, water etc – which his lawyers smuggled out of his prison in Algeria. But Macron is the first head of state to speak openly about these wartime practices as more or less systemic: France's Jupiterian president, formerly a banker and a corridor consigliere inside the Elysée, is something of a systems intellectual.

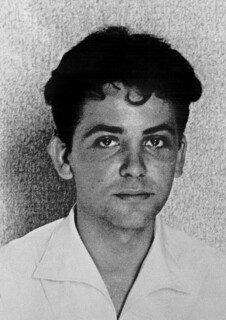

The man on Macron's conscience is Maurice Audin, a French mathematician who disappeared during the Battle of Algiers (1956-57). Audin was born in Tunisia, the son of a gendarme; the family moved to Toulouse and then emigrated to Algeria. At the time of his disappearance he was 25, lecturing at the University of Algiers and winding up his doctoral dissertation. He was also a member of the Algerian Communist Party, which had been dissolved by the French government two years earlier and was now working in secret alongside the Front National de Libération. Audin was arrested in June1957 in a raid on his flat in Algiers. In April it had been used by two party members as a makeshift doctor's surgery: one of them was a senior figure in hiding who had fallen ill; the other was a lung specialist, Dr Georges Hadjadj. Audin was taken away; his wife, Josette, and their children were held under guard in the flat.

Audin was interrogated in a half-finished seven-storey building in the suburb of El Biar, requisitioned by the paras as a 'sorting centre'. The day after he was arrested, Alleg called round at the Audins' flat, only to encounter the guard. He too was taken to El Biar. Before his own ordeal began, he was given a glimpse of Audin by his captors (Audin, strapped to a table, told him how 'hard' interrogation would be). This makes Alleg one of the last civilians to see Audin alive. Hadjadj was another: he had been detained shortly before his comrades and tortured for three days in El Biar. He had given his interrogators Audin's name, not during one of the sessions but in a moment of physical respite, when he was told that his wife might be brought to the building to take his place. Hadjadj and Audin spent several hours together in a cell a few days before Audin's disappearance.

Hadjadj and Alleg survived El Biar, unlike Audin. According to his tormentors, Audin contrived an 'escape', but when they informed Josette, she understood exactly what was meant. As Macron's declaration has it, her husband was 'tortured then executed, or tortured to death'. The details of Audin's death aren't clear. It's possible that his captors stage-managed a preamble that would lend weight to the story of his escape, and that they hoped to dupe Alleg into believing it: Alleg was told by Lieutenant André Charbonnier, the presiding officer at El Biar, that he should prepare for a journey by car with Audin and Hadjadj, but then heard Charbonnier give orders for the other two to be removed separately. Later Alleg heard bursts of gunfire outside, possibly part of a pantomime to persuade Alleg that Audin had made a run for it and got away.

One version of Audin's death, based on a lone but plausible source, is that he was strangled by Charbonnier in a moment of rage during an interrogation. Pierre Vidal-Naquet, the author of L'Affaire Audin (1958), came round to this view. Other accounts include the suggestion that he was mistakenly executed in place of Alleg, an influential journalist and a nuisance to the colonial authorities; that he was killed on the direct orders of two of France's senior military men in Algeria, Brigadier General Jacques Massu, the para commander who masterminded the Battle of Algiers, and his enthusiastic henchman Pierre Aussaresses, a lower ranking officer in charge of intelligence. Many years after the event Charbonnier insisted in private to his son that he had handed over Audin to his senior commanders but that esprit de corps had kept him from full disclosure. What other explanation would a retired French officer accused of strangling a young French mathematician with three children give to his own child?

The afterlife of Maurice Audin owes its persistence to his widow – along with many friends and academics – who wouldn’t let the story die with her husband. The evolution of the Audin affair tells us how resistant the state and the military used to be when their deeds were called into question. Over the years, that resilience has weakened as calls for acknowledgment have kept coming, along with growing numbers of investigative pieces into Audin's disappearance. Aussaresses defended his role as a torturer but most of the men who observed the omertà of the para regiments took their secrets with them to the grave.

Can Josette Audin seriously have thought, when she filed a complaint against unknown persons for the voluntary manslaughter of her husband in 1957, that she would shine a light into the obscurity of France's warrior state? Over the years, one suit followed another, to no avail, but Audin's death was a nagging sore. The crime came to stand for many of the atrocities committed during the Algerian war. French presidents, one after another, were approached by support committees, associations, mathematicians and historians with a view to a statement on the Audin murder.

Mitterrand held aloof: he'd had a compromising spell in Vichy and understood the damage that the past can inflict on a man of the moment. Then, too, as minister of justice in the 1950s, he was notoriously unwilling to grant pardons to anti-colonialists destined for the guillotine in Algeria. Chirac, unlike his predecessors, was clear about the state's role – and to some extent the role of 'France' – in the deportation of 75,000 Jews under Vichy and the Nazi occupation. He also acknowledged the massacres in Sétif and Guelma in 1945. But he wasn't going to start a conversation about Algeria on the terms that Algiers was proposing (official recognition by France of its guilt). Audin was a trifle he could afford to ignore, and Sarkozy took the same view. Hollande was the first head of state to admit that Audin died in detention, and the first to commemorate the many deaths of Algerian pro-independence militants in Paris in 1961.

Macron has gone further, saying that ‘a system known as “arrest-and-detain”’ was the necessary condition for Audin's death – to which we could add three thousand other deaths and disappearances, the vast majority Algerian, during the Battle of Algiers. He explains that the granting of ‘special powers’ to the government in 1956 paved the way for a handover of authority in Algeria, by decree, to the army and police. Which is to say that every unlawful act that followed had its origin in legal, constitutional measures. The only way to set this right, the argument runs, would have been to call out and punish persons responsible for torture. Governments that failed to do so endangered the lives of detainees, though according to Macron, responsibility lay in the end with the security services.

Significantly, the 'special powers' in Algeria were granted in the wake of an earlier law declaring a state of emergency. It wasn't in force in 1956 because the government that had voted it in had been dissolved. But the state of emergency was invoked again in 1958 and has been used several times since: most recently by Hollande after the jihadist atrocities in Paris at the end of 2015. It was rolled over six times and finally lifted by Macron last year. But there was an ominous quid pro quo: several of the provisional powers that an emergency confers on the state and the security forces had been written into the constitution the previous day.

One of the suits that Josette Audin filed on behalf of her husband was a complaint of 'illegal confinement and a crime against humanity'. That was in 2002. In 2017, during a visit to Algiers, candidate Macron used the same expression – 'crime against humanity' – to describe the colonial process. It was part of a past, he added, for which 'we should apologise'.

The declaration on Audin and Macron's pledge to open up what remains of the archives from those bleak years is as close as it gets to an apology. It comes as a relief to the family, whom Macron visited last week to present the declaration. It also raises the possibility of far more cordial relations between Algeria and France, and as the historian Benjamin Stora writes, France's is not the only archive: both parties to the conflict should open the records. Not everyone in France is happy. The response from African media has been mixed. Jeune Afrique, edited in Paris, called Macron's decision a 'historic gesture'. 'Courageous but insufficient' was the headline in Le Quotidien d'Oran, above an editorial that called for 'the implacable pursuit of the duty to commemorate'. El Watan, an Algerian daily, was in favour, and saw it as the end of a 'historic denial'. More likely the beginning of the end.

Undated photograph of Maurice Audin / AFP / Archives

Comments

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/jul/02/victoriabrittain

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mehdi_Ben_Barka

Colonial Powers in Africa kept the bagmen on payroll well after the flag came down:

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/poverty-matters/2011/jan/17/lumumba-50th-anniversary-african-leaders-assassinations

Perhaps one day a museum in Paris will commemorate their victims:

https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2018/08/16/chile-now-more-than-ever

Although, going by history of hissy fits thrown by right-wingers, I wouldn't count on it going up any time before 2050:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/world/monitoring/media_reports/1604970.stm

Gillian Dalley

London