Carlsen’s Fortress

Andrew McGettigan

Bafflement reigned in the press room last night at the end of the final scheduled game in the World Chess Championship. Magnus Carlsen, the reigning champion, appeared to let his challenger off the hook by offering a draw from a position of strength. Well behind on the clock, Fabiano Caruana swiftly accepted. Carlsen’s comments after the game indicated that he had less confidence in his chances than the watching grandmasters with access to supercomputers.

The match therefore reached an unprecedented conclusion: all 12 games were drawn. There will be a tie-break on Wednesday, when up to 15 quick games will be played in a single session. Carlsen is the favourite, given his domination in the faster forms of chess. He has never lost a play-off.

Yesterday, the players stuck to the pattern of previous games, with Carlsen going for the Sicilian Defence, the most double-edged of the openings available to Black. He sprung a surprise at move 8, however, diverging into a variation usually reckoned to be weaker. (The line had been defended in a computer-only tournament in April.) Caruana used up much of his allocated time only to produce an artificial plan that weakened his position on both flanks. He started to go backwards on move 24 and Black took over the whole board. Carlsen kept a firm hold on the position without ever committing to moves that would force things towards a decisive conclusion. The early peace offer suggests that nerves are affecting both players, but Carlsen is confident about Wednesday.

The match has been marked by a mix of sharp fighting play – when Carlsen played with Black – and some insipid draws when colours were reversed. Both players have come close to winning and both have shown high-level defensive skills. Carlsen had the clearest opportunity to win in the very first game; otherwise Caruana had the better of it until the last hour.

Carlsen has obvious appeal to amateurs and sponsors (the logos of four are embroidered on his suits and shirts). He grimaces, sighs, lolls in his chair, flings his arm over the headrest, fidgets with captured pieces and displays moments of hesitation when his hand hovers over a piece only for it to be snatched back as he reviews what he wants to do. At times he turns towards the audience, in the darkened theatre behind a double layer of soundproofed glass, possibly looking at his reflection.

Caruana, by contrast, perched on his outsize chair, rarely offers any aspect other than focused concentration, with his hands always near his cheeks and lips. His only tell in difficult positions is his pallor, whereas Carlsen can be spotted muttering variations to himself while working through a range of facial expressions. When adjusting their knights on the board, Caruana rotates them so that they face his opponent, Carlsen so that they offer their profiles, looking either left or right towards the centre of the board.

After a near catastrophe in the opening game, Caruana played himself into the match impressively. Carlsen wasted the traditional advantage of playing with the White pieces by repeatedly making conservative moves early on. Prima facie, his aim has been to get simplified positions with queens removed from the board, where his skills in the endgame can come to the fore. But he underestimated the strides made in this department by the man sitting opposite him. Carlsen's decisions at early stages of games 6 and 11 received particular scorn from commentators: one went on strike and another described Carlsen’s decisions as ‘shocking’.

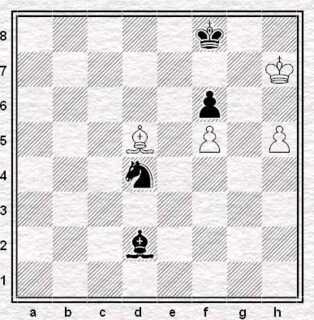

I should single out Carlsen's miraculous defence in Game 6, which enabled him to draw even though a piece down. The fortress he constructed will enter the endgame anthologies as he skilfully arranged his few remaining pieces and pawns to prevent Caruana from progressing towards the win his material advantage promised. Had the position been composed as a study it would have been admirable; that it was devised during play was astounding.

Carlsen’s fortress in Game 6 (diagram prepared using Alain Blaisot’s DiagTransfer). It is White’s turn to move. His bishop can keep the Black knight from key squares while it shares duties with the White king to keep the Black king from g8 and h8. The White pawns are on white squares, immune to the Black bishop. If Black tries to bring his king round to attack White's pawns from behind, then the White king attacks the remaining Black pawn on f6, which Black needs to win, or ushers the h5 pawn through to its queening square.

Game 10 was a slugfest as Carlsen sacrificed a pawn on one side of the board for the sake of an attack against his opponent's king on the other. As in so many of the contests, Carlsen playing black had been out-prepared by Caruana, but found a bold way to wrest back the initiative. Only strong defence defused the threatening build-up of Carlsen's forces. The resulting endgame was so complex that some of the watching grandmasters had to leave the building to get some air. After move 40, Carlsen overpressed and the advantage swung back to Caruana, but an accurate sequence from Carlsen steered play into a draw.

Game 11, easily the dullest of the match, was enlivened by the one moment of controversy. Before Game 4, Caruana's home base, the St Louis chess club, published a video online, swiftly taken down, showing behind-the-scenes shots of his training camp. It apparently revealed a set of lines that Caruana was preparing to defend as Black – and one of them showed up in the penultimate game. That Carlsen seemed to have little in his locker against it only underscored his lacklustre strategy, though I suspect that he was suffering from a cold and was aiming perhaps for a position he could not lose, his germs offering an across-the-board threat.

He is unlikely to have been concerned about the Pinkerton detective agency, announced as official ‘anti-cheating partners’ by World Chess the day after the video appeared. Other, more literal-minded attempts to sex up the game include a chess dating app, a Kama Sutra style logo that was dropped for being too racy but can still be found on T-shirts for sale at the venue, and a perfume range (‘King's Gambit’ and ‘English Opening’).

Tomorrow afternoon, the players won’t have much opportunity to recover between rounds. They will begin with four Rapid games, in which Carlsen will play White in the first and third bouts. Official performance statistics, which predicted the six-all draw in the 12 Classical games, point to Carlsen winning the first tiebreak 2.5-1.5. If it’s a draw, however, Blitz games will follow, in which each player gets five minutes’ thinking time at the start of the game, with three seconds added as each move is played. The ratings suggest Carlsen should score over 70 per cent; Caruana is only the world number 16 at Blitz.

The title cannot be shared and three weeks of chess will, if the Blitz round is drawn, conclude with an Armageddon game, in which White starts with five minutes and Black with only four. But Black’s advantage is probably greater: in the event of yet another draw, the title goes to the player who started the Armageddon game as Black. Everyone will want to avoid such a decider.

Comments

Carlsen played the inaccurate 67 Nh7-g6 which allowed a rather unlikely winning sequence which is explained as well as can be here by 8-time Russian champion, Peter Svidler: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XVowybk-GmE