Genuine Scotch Mist

Caroline Eden · Ella Christie’s Japanese Garden

Sakoku, Japan’s 200-year policy of national isolation, ended in 1854. As breathless British travellers returned home, writing of their adventures, interest in Japanese-style gardens blossomed. ‘The mountains of Japan are covered with forest,’ the naturalist Isabella Bird wrote in 1876, ‘and the valleys and plains are exquisitely tilled gardens. The Empire is very rich in flowers.’

The craze was brisk. Josiah Conder’s influential book Landscape Gardening in Japan was published in 1893. Gunnersbury Park laid out its Japanese Garden in 1901. There were nurseries, such as Gauntletts of Chiddingfold, that specialised in Japanese styles, lanterns and imported plants. White City hosted the Japan-British Exhibition in 1910. Dwarf trees, bamboos and pines were shipped from Japan for the exhibition’s Garden of Peace and Garden of the Floating Isles. Over six months, eight million visitors came hoping to be transported to Japan via authentic tea houses and replica ‘peasant’ villages, which the Japanese press found embarrassing.

Two years before London’s blockbuster exhibition, another Japanese garden had been planted at Cowden Castle in Clackmannanshire. Isabella (‘Ella’) Robertson Christie (1861-1949) had visited Japan in 1907 and returned home with plans to create her own pleasure garden. Overseen by Professor Jijo Suzuki, the 18th hereditary head of the Soami School of Imperial Garden Design, and designed by the horticulturist Taki Handa, the garden was maintained by Shinzaburo Matsuo. Once it reached maturity, Suzuki declared it ‘the best garden in the Western world’.

Ella described the garden in A Long Look at Life by Two Victorians, written with her sister:

In a sheltered foothold of a grassy range of hills, that stretch from sunrise to sunset, lies the garden of my dreams. As its background softly rounded hills breathe peace, after the fierce volcanic agencies that upraised them, and long aeons of time have moulded their forms into the undulating lines that encircle the surroundings of Shah-rak-uen, the place of pleasure and delight.

It was short-lived. Three years after Ella’s death in 1949, aged 87, Cowden Castle was demolished. The garden opened to the public for the last time in 1955. In 1963, teenagers broke in and demolished it, burning the tea houses, bridges, lanterns and shrines. But since 2014, with funds raised by Ella’s great-nephew, Robert Christie Stewart, and his daughter, Sara, a Japanese-British team led by Masao Fukuhara of the Osaka University of Arts has been restoring the garden. It will open to the public towards the end of May.

I went to see it last year. The work had been painstaking and precise, Sara Stewart told me. It took eight hours for one particularly important stone to be precisely positioned by a digger, under Fukuhara’s watchful eye. ‘Stones are key in Japanese gardens. They last a millennium, while plants come and go. Looking at a stone garden, without plants, a Japanese would say: “It’s all here.” Whereas a Westerner, seeing something akin to a quarry, would likely say: “It’s all gone.”’

Ella continued her travels after returning from Japan. She went to St Petersburg in 1912, and journeyed on by train, steamer and droshky to Tashkent, Samarkand and Khiva (a slave-trading town in modern-day Uzbekistan that she was the first British woman to visit). Through Khiva to Golden Samarkand was published in 1925. It’s deliberately less gung-ho than books by such male travel writers as Arminius Vámbéry, Peter Hopkirk and Fitzroy Maclean. Ella doesn’t set out to break records, traverse mountain ranges or gain accolades. ‘My reasons for making the journey were twofold,’ she writes: ‘first, the extreme desire to see for myself what lay on that comparatively bare spot on the map east of the Caspian Sea … and secondly, the lure of those magic names, Bokhara and Samarkand.’

Before she set off, the Foreign Office warned her of ‘plague’ and smallpox (she was vaccinated in Constantinople). Should she contract the disease, she ought to ‘hang a red cloth over the window,’ they said. But ‘no thought was given as to where red cloth was to be obtained,’ Ella comments, or ‘if there would be any windows over which to hang it.’

She describes the ice lollies sold in the bazaar, made by chiselling down a block of ‘frozen snow’ and pouring raisin syrup over the chips; she wouldn’t get out of her carriage on the steppe for fear of the ‘Kara-kourt’, a black spider whose venom could kill a camel in three hours; she ate eggs cooked over a spirit lamp. A sandstorm blowing in at night by the banks of the River Oxus, where once ‘Alexander and Tamerlane slaked their horses’ thirst’, reminded her of ‘genuine Scotch mist’.

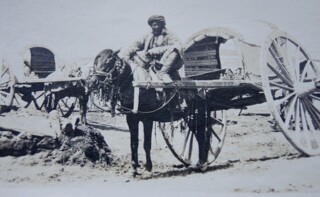

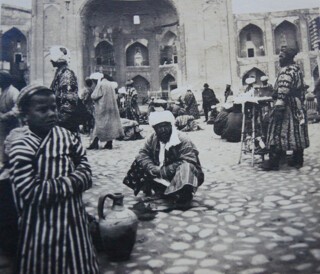

At Robert Stewart’s dining table, we flicked through boxes of Ella’s black and white photographs, most no bigger than a playing card. (Local children would ‘run like the wind’ when they saw her Kodak, she wrote.) The pictures show men cooking rice on the street in Samarkand; merchants bargaining in Khiva; silk weavers working beneath mulberry trees; Samarkand’s main square, the Registan, and the grounds of Tamerlane’s mausoleum, the Gur-i-Emir, crumbling and falling down, quite different from the over-restored buildings of today, but their layout instantly recognisable.

Robert remembers his great-aunt Ella as a generous woman. But she hated social chit-chat. A man on the platform at Dollar railway station once asked if she was going to Edinburgh for the day. ‘No,’ she shot back. ‘I am going to Samarkand!’

Comments

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/84/Dolllartown.jpg

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/32/RumblingPark.jpg