The UFOs we want

Cal Revely-Calder

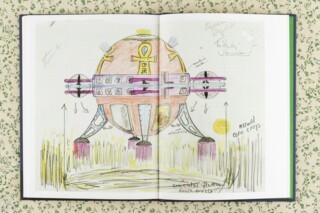

A UFO drawing from the National Archive.

In 2007, the US Department of Defense launched the Advanced Aerospace Threat Identification Program to collect sightings of ‘anomalous aerospace threats’ – in demilitarised English, Unidentified Flying Objects. The programme had cost the Pentagon $100 million by the time they cut the funding in 2012. Last year, the New York Times and Washington Post got hold of some AATIP files, but it was disappointing to hear how conventional they sounded; UFOs haven’t changed much since the 1960s, defying physics and outrunning fighter jets.

Still, the programme lasted five years (and may unofficially go on) not just because of the perennial worry that UFOs might pose a military threat, but because many of the witnesses this time round were military personnel. When Luis Elizondo, the officer who ran the AATIP desk, quit the Pentagon altogether, he said that funding had been blocked by sceptical superiors – which seemed especially unconscionable to him, given that it was ‘the Navy and other services’ who’d been sending him reports. Military UFO witnesses should be harder for sceptics to dismiss: they’re disciplined, and trained, and subject to psychological screening. They do not wear anoraks, or run non-mainstream blogs, or send their stories to MailOnline.

AATIP wasn't the DoD’s first UFO programme. Projects Sign, Grudge and Blue Book ran from 1948 to 1970. Even then the funding was poor, and many senior officers were hostile. You can read most of the files online, in redacted form, in the US National Archives, though it’s a shame that the transfer from microfilm has damaged photos that were too rarely kept on file.

On this side of the Atlantic, we’ve had better luck. The Ministry of Defence ran a UFO desk from 1952 until 2009; it was as underfunded as its American cousins, but it collected as many sightings (12,000) and was a bit more tolerant. Many of the MoD reports were accompanied by illustrations – diagrams, photos, sketches, even paintings – that were duly filed away. When the Freedom of Information Act was passed in 2000, the UFO desk was inundated with requests. The MoD knew better than to put up a fight. They’d seen nothing definite in over fifty years, so from one point of view the files were too trivial to hide.

David Clarke, a lecturer in journalism at Sheffield Hallam University, was made a consultant at the National Archives, where he spent ten years overseeing the UFO files’ release. There may be no extraordinary revelations in them, in the sense a UFOlogist would like, but there are fruits of a different sort. Clarke recently curated a peculiar and beautiful book called UFO Drawings from the National Archives, a showcase of the best ‘imaginative artwork’ sent to the MoD, ranging from scribbled crayon disks to diagrams in tidy pencil.

The book takes an old question (what did these people see?), sidesteps the nutjob theories and gives us a form of social history. There were an average of 100 to 200 sightings a year, but the numbers spike, here and there. There were 750 reports in 1978, immediately after Close Encounters of the Third Kind was released; the figure didn’t dip below 200 until 1985, after Alien, E.T. and The Thing had been and gone at the cinema. In the images from these years, some of the spacecraft have ladders or beams of light sliding down to earth. An earlier one (from 1972) is soaring heavenward, and looks a lot like Thunderbird 3. We get the UFOs we want.