Travelling to Find Out

Hanif Kureishi

One night, I went on a boat trip down the Bosporus with about a dozen models, fashionistas, several transvestites, someone who appeared to be wearing a beekeeper’s outfit as a form of daily wear, the editor of Dazed and Confused Jefferson Hack, and Franca Sozzani, the editor of Italian Vogue. We were in the European capital of culture, but it was like a fabulous night at the London club Kinky Gerlinky transferred to Istanbul and financed by the Turkish Ministry of Culture. At one end of the boat, in his wheelchair, was Gore Vidal. At the other end was V.S. Naipaul. It must have been June 2010 because I remember catching Frank Lampard’s ‘ghost goal’ against Germany on a TV in the hotel lobby just before we dashed out.

As the high-tech drum and bass beat on, and the Ottoman palaces drifted by, we godless, depraved materialists and hooligans became more drunk, stoned and unruly. Vidia, with his entourage, kept to his end of this ship of fools, and Vidal to his. We had been instructed to keep the two aged warriors apart, and I don’t believe they exchanged a single word during the four days we were in Turkey. Vidal was accompanied by two ‘nephews’, strong young men in singlets and shorts who took him everywhere. He was unhappy, usually violently drunk, occasionally witty, but mostly looking for fights and saying vile things. Vidia, in love and cheerful at last, accompanied by the magnificent Nadira, remained curious, ever observant and tight-lipped. Earlier, despite his supposed animus against female writers, he had been keen to talk about Agatha Christie and how fortunate she had been never to run out of material. In contrast, from a ‘small place’, he himself had had to go on the road at the end of the 1970s, to explore the ‘Islamic awakening’, as he put it. He had been ‘travelling to find out’.

I had packed Naipaul’s Among the Believers, as a kind of guide, when I first went to Pakistan in the early 1980s to stay with one of my uncles in Karachi. I wanted to see my large family and get a glimpse of the hopeful country to which my uncle Omar – a journalist and cricket commentator – had gone. Like my father and most of his nine brothers, Omar had been born in India; he had been educated in the US with his schoolfriend Zulfikar Bhutto, finally turning up in Pakistan – ‘that geographical oddity’ – in the early 1950s. In his memoir, Home to Pakistan, he wrote: ‘There was in the early Pakistan something of the Pilgrim Fathers who had arrived in America on the Mayflower.’

At night, alone at the back of the house, I had insomnia, and felt something of a stranger myself. In an attempt to place myself, I began to work on what became My Beautiful Laundrette, writing it out on any odd piece of paper I could find. In Britain we were worried about Margaret Thatcher and her deconstruction of the welfare state of which I had been a beneficiary. I wanted to do some kind of satire on her ideas, but in Karachi they barely thought about Thatcher at all, except, to my dismay, as someone who stood for ‘freedom’. My uncles and their circle were more concerned with the increasing Islamisation of their country. In Home To Pakistan Omar wrote: ‘There is an appearance of a government and there is the reality of where real power lies. I had serious doubts that we would become an open society and that democracy would take root.’ Zulfikar Bhutto had been hanged in 1979 and his daughter Benazir was under house arrest just up the street, at 70 Clifton Road, a property with a huge wall around it, and policemen on every corner. One thing was for sure: my family, like Jinnah, had envisaged Pakistan as a democratic home for Muslims, a refuge for those who felt embattled in India, not as an Islamic state or dictatorship of the pious.

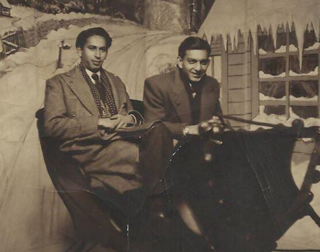

Zulfikar Bhutto (left) with Omar Kureishi

Naipaul, who in the late 1970s travelled around Malaysia, Indonesia, Iran and Pakistan, had grasped early on that this distinction no longer held up. In Among the Believers – surprisingly without preconceived ideas, and with a shrewd novelist’s eye for landscape and individuals – he interviews taxi drivers, students, minor bureaucrats and even a mullah. He writes down what they say and mostly keeps himself out of the frame. As a teenager I had been a fan of what had become known as personal journalism, of firecracker writers like Norman Mailer, Tom Wolfe, Hunter S. Thompson, Joan Didion and James Baldwin, imaginative writers who included themselves in the story, and who often, as with Thompson, became the story itself. Naipaul, in one of the first reports from the ideological revolution, was doing something like this. But he was more modest, a writer of loss and restlessness. From Chaguanas, Trinidad (‘small, remote, unimportant’), he now travels widely, has an extensive look around and actually listens to people – mostly men, of course. He never interviews anyone as intelligent as he is, but he is genuinely curious, a rigorous questioner and not easily impressed. He even greets one subject, in his hotel room, while wearing ‘Marks and Spencer winceyette pyjamas’, of which he is so proud he mentions them twice.

Around the same time, Michel Foucault – more leather than winceyette – visited Ruhollah Khomeini outside Paris, and went to Tehran twice. Foucault, who was fascinated by the extreme gay lifestyle he found in San Francisco, had also written for the Corriere della Sera defending the imams in the name of ‘spiritual revolution’. This inspiring revolt or holy war of the oppressed, he believed, would be an innovative resistance, an alternative to Marxism, creating a new society out of identities shattered by domination. It was new. But as Naipaul discovered, there was very little spirituality about this power grab by the ayatollahs. Soon they were hanging homosexuals from cranes; women had to wear the chador. Even in Pakistan women covered up before they went out, and no one in my family had been veiled before. One of my female cousins revered Khomeini – ‘the voice of God’ – as an example of purity and selfless devotion. He was everything a good man should be. But she also took me aside and begged me to help her children escape to the West. Pakistan was impossible for the young; everyone who could was sending their money out of the country, and, when possible, sending their children out after it, preferably to the hated but also loved United States or, failing that, to Canada. ‘We want to leave this country but all doors are shut for us,’ my cousin wrote to me. ‘Do not know how to get out of here.’

‘Fundamentalism offered nothing,’ Naipaul wrote. He didn’t find much to idealise. The people Naipaul is drawn to want more, but they don’t know what it is. They are aware of their relative deprivation, but gullible – just like the protagonist of Naipaul’s masterpiece, A House for Mr Biswas. Biswas becomes a journalist; he is working on a story called ‘Escape’. But he is too intelligent for his surroundings. He becomes hysterical, endlessly dwelling on his wounds and victimhood. He is subject to a power – colonialism – that always humiliates him, and he has internalised its contempt. There is only one way out: the belief that at least your children will have better lives than you. Biswas’s clever son, Anand, is Vidia Naipaul: the one who would escape to Oxford, work for the BBC and become a writer. Naipaul had done all that, but he had also learned that you can’t escape the past. Now travelling in places like those he came from, he found a proliferation of anxious, wounded men like his father.

But this time round, their sons wouldn’t fester. They would turn to a new machismo, a politicised Islam, ‘because all else had failed.’ Late in Among the Believers, Naipaul runs into my cousin Nusrat Nasarullah, then a journalist for the Morning Star. Nusrat, with his ‘fruity voice and walrus moustache’, tells him: ‘We have to create an Islamic society. We cannot develop in the Western way. Development will come to us only with an Islamic society. It is what they tell us.’ Around the time of the Iranian revolution Bob Dylan released ‘You Gotta Serve Somebody’, which elaborates the impossibility of not being devoted to someone or something. Seeking a space outside of the colonisers’ ideology, Naipaul’s subjects in Among the Believers could only repeat – only this time more harshly – what had already been done to them. What began as an indigenous form of resistance, cheered on by a few Parisian intellectuals, soon became a new, self-imposed slavery, a self-subjection with an added masochistic element – one manifestation of which became Osama bin Laden’s devotion to death. Hence the helplessness and disillusionment that Naipaul found. If the coloniser had always believed the subaltern to be incapable of independent thought or democracy, the new Muslims confirmed it with their submission. They had willingly brought a new tyrant into being, and He was terrible, worse than before. One of the oddest things about my first stay in Karachi was endlessly hearing people tell me how they wished the British would return and run things again. There were many shortages in Pakistan, but that of good ideas was the worst.

A few months after the Bosporus boat trip, Naipaul was invited to Turkey again, to address the European Writers’ Parliament, an idea of José Saramago’s. This time there was an uproar: Naipaul was said to have insulted Islam after saying in an interview that ‘to be converted you have to destroy your past, destroy your history.’ Naipaul never returned to Turkey – where now, as we know, there are more than three hundred journalists and writers in jail. Legitimate anger turned bad; the desire for obedience and strong men; a terror of others; the promise of power, independence and sovereignty; the persecution of minorities and women; the return to an imagined purity. Who would have thought this idea would have spread so far, and continue to spread?

Comments

-

30 August 2018

at

10:06pm

Ludmila Sakowski

says:

Excellent writing. Excellent insight. Thank you.

-

31 August 2018

at

12:08am

gary morgan

says:

Interesting Kureshi notes VSN was a good listener who kept himself out of frame, though not really, not in the angry, funny and brilliant travel books. I loved these tomes and reread them still, not least as I loved his cool and elegant style.

-

31 August 2018

at

11:42am

Sandarak

says:

Great piece and thought-provoking. But Islamist politics were something of a Western brain child in Turkey, encouraged by people who accepted the idea that secularism was a bad thing -- for Turks though perhaps not for Brits and Americans. Ironically the people who led the campaign to revoke Naipaul's invitation to Turkey were the Guelenists of Zaman (a religious newspaper shut down in 2016 and its editors and columnists who are mostly now in jail. The number is smaller than 300 though. About half that.) And in Washington, London, and other capitals the Guelenists still seem to drown out the views of secular Turkish liberals and leftists the sort of Turks who had no objection to Naipaul. The West shouldn't see Islamist politics just as a dreadful mistake by people who do not know what they are doing and for which contemporary Westerners share no responsibility.

-

31 August 2018

at

12:05pm

Simon Wood

says:

What an opener, what a vivid non-meeting of Naipaul and Vidal - one might say, cruelly, "Two shits passings in the night".

-

31 August 2018

at

12:06pm

Simon Wood

says:

(Agh, "passing" not "passings" in main gag, line 2.)

-

1 September 2018

at

11:36am

Joe Morison

says:

@

Simon Wood

I only noticed, Simon, when you drew attention to it (and I think we’ve all experienced that ‘agh!’). It’s a rigorous discipline, with no editing possible, commenting on this blog - whether it’s policy or limited resources, I’ve no idea.

-

2 September 2018

at

10:11pm

Simon Wood

says:

@

Joe Morison

Thanks, Joe, maybe it's not worth drawing notice to mistakes. Interesting, this whole nuance thing that people are going on about.

-

2 September 2018

at

10:49am

L. Coats

says:

'A dozen models...' Kureshi's faintly dehumanising quantification would be a simple party-brag but for the article's contemplation of oppression as it affects 'fathers and sons'. In that context it looks more like one writer's sexism match-cut with another's, in the name of literary appreciation.

-

3 September 2018

at

3:18am

philip proust

says:

@

L. Coats

Valid point, L. Coats.

-

3 September 2018

at

7:42am

Jake Bharier

says:

Motes and beams? "model" isn't qualified by gender. There are male models. Of course, they could be Hornby, though I don't think context supports this.

-

11 September 2018

at

5:39pm

deadsparrow

says:

@

Jake Bharier

They were at the other end of the boat, with Vidal.

-

3 September 2018

at

9:20am

steve kay

says:

There might be an ongoing academic discussion of the socio-economic differences between Hornby and Triang as model brands, but that has even less to do with the original context.

-

3 September 2018

at

9:43am

Graucho

says:

@

steve kay

Just a train of thought.

-

5 September 2018

at

9:09pm

Charbb

says:

Travelling to finmd out? But how little he found out ! Compare his two whining doleful abject books on India ("An area of Darkness" and "India: A Wounded Civilization"), seeing nothing but despair and failure and absurdity, predicting only perdition - and compare them with the robust, thriving India of today. Ask yourself why Naipaul was so blind. He reduced everyone to his little measure. He was a small. frightened man, and he had an eye only for human weakness, never human courage and ability to overcome. Westerners admire him because he flatters their feeble egos. Tells them they are strong and the poor countries are nothing. notice how since the rise of India and china and the withering of the SWest Naipaul has wilted and dated.

-

5 September 2018

at

9:11pm

Charbb

says:

Travelling to find out? But how little he found out ! Compare his two whining doleful abject books on India ("An Area of Darkness" (1965) and "India: A Wounded Civilization" (1977) ), seeing nothing but despair and failure and absurdity, predicting only perdition - and compare them with the robust, thriving India of today. Ask yourself why Naipaul was so blind. He reduced everyone to his little measure. He was a small. frightened man, and he had an eye only for human weakness, never human courage and ability to overcome. Westerners admire him because he flatters their feeble egos. Tells them they are strong and the poor countries are nothing. notice how since the rise of India and china and the withering of the West Naipaul has wilted and dated.

-

5 September 2018

at

9:21pm

Charbb

says:

I recently looked at Naipaul's 1977 jeremiad "India: A Wounded Civilization". I was embarrassed at its blind hysteria, its lack of any sense of the future. His was a shopkeeper mind. The cash balance is his only way to measure human beings. His famous line, "Men who are nothing, men who allow themselves to become nothing, have no place in [the world]" is much lauded by other small souls, but it is hollow. Show me a human being who is "nothing". Human beings are only "nothing" for worthless people.

Read moreOf course he often impersonated Colonel Blimp to a T; and at a lecture I was enthralled and occasionally appalled at his open anger at those he suspected were "Marxists"; some were but often he excoriated what seemed to me innocent enquiries as if they ideological forays (there were many of the latter of course).

He certainly made me think and I miss those books - though none since 'The Enigma of Arrival.' And I rate 'A Bend in the River' highest: he had a nose for incipient trouble and the Congo was cleverly judged by him.

The Hitch thought the great CLR James a better writer, a finer stylist. Not me, for all that Hitchens is a favourite of mine too, as is Derek Walcott, no friend of our man.

RIP Vido. "Naughty but Nice"!

I wonder what Naipaul would have made of Anton Wilhelm Amo (1703-59) who was taken from Ghana to Germany as a boy, given as a present to a prince and studied at school and universities, finally at Wittenberg where Hamlet went.

He returned to Ghana in his later years but people were suspicious of his outlook and German philosophy. It may be that he failed to fit in.

A good person to write up Naipaul's novelisation would be Jonathan Swift, of a man marooned between Africa and logic. His version would warn us about sinking into the already depressed and battered leather sofa of cynicism, along with Naipaul, Vidal and Hitch.

Thank God for Hanif Kureishi and modern London.