A Jar, a Blouse, a Letter

Maria Dimitrova · The Kristeva Dossier

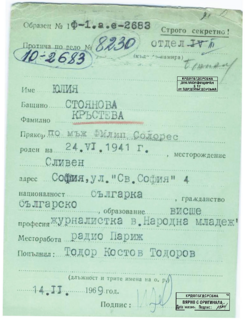

In Laurent Binet’s novel The Seventh Function of Language (2015), Julia Kristeva is cast as a spy for Bulgarian intelligence, responsible for the death of Roland Barthes. Last Tuesday, the Bulgarian Dossier Committee, in charge of examining and declassifying communist-era State Security records, announced that Kristeva had been an agent of the First Chief Directorate.

On Thursday, Kristeva denied the allegations, describing them as ‘grotesque’ and ‘completely false’. On Friday, the Dossier Commission published her entire dossier – nearly 400 pages – on their website. Yesterday, Kristeva issued another statement, insisting she had ‘never belonged to any secret service’ and had not supported ‘a regime that I fled’. She criticised the ‘credence given to these files, without there being any questioning about who wrote them or why’:

This episode would be comical, and might even seem a bit romantic, were it not for the fact that it is all so false and that its uncritical repetition in the media is so frightening.

The dossier consists of a ‘Work’ file (documents attributed to Kristeva), a ‘Personal’ file (documents collected about Kristeva) and forms and cards registering her as a ‘secret collaborator’ (dated 14 November 1969) and an ‘agent’ (21 June 1971). A faint inscription in pencil next to her name on one of the forms says ‘Refugee’: a dangerous status for her to have, especially for her relatives. ‘The contact with our authorities should be kept alive,’ Kristeva’s father advises her in a letter. ‘People should feel that in you and your sister they have grateful, patriotic fellow citizens. Such a contact will make our life here easier.’

State Security divided Bulgarians abroad into two camps: loyal and ‘enemy’ émigrés. A glance at Kristeva’s ‘Personal’ file – three times the size of her ‘Work’ file – reveals that she was under close surveillance from the earliest years of her career. Her private correspondence, her academic and journalistic work and her conversations with other Bulgarians were closely monitored, and information about her family was methodically collected. Sixteen officers worked on her case. The contents of one intercepted package read: ‘a jar, a blouse, a letter’.

Born in Sliven in 1941, Kristeva was first taught French by Dominican nuns in a Catholic convent. After they were expelled from Bulgaria on suspicion of espionage, she was transferred to a secular French school (the English school was open only to the children of party members). She graduated from Sofia University at the top of her class, was active in youth organisations and worked as a journalist for several publications including Narodna Mladej. In 1965 she was authorised to go to Paris to study for one year. But she stayed longer and in 1967 married Philippe Sollers. In 1970, according to a report in her ‘Personal’ file by agent ‘Petrov’, following a successful ‘recruitment talk’ she was added to the ‘agent apparatus’ under the alias ‘Sabina’.

‘In those years, there were only three ways to leave the country,’ a former member of the Dossier Commission told me. ‘You had to be a cop, have a relative in the party, or agree to collaborate with State Security.’ Everyone had a ‘verbovachna beseda’ – a recruitment talk – ‘and many never forget it for the rest of their lives.’ Agent Petrov describes Kristeva admitting she felt ‘a little uncomfortable’ because of her marriage to Sollers: before going to France, she had declared that she had no intention to marry or settle there, and was now afraid that her actions would be negatively interpreted. Petrov reports her as saying that in Paris she has become an even ‘stauncher adherent to socialism because of the trust our authorities placed in her by letting her go to Paris and allowing her parents to visit her’. ‘I asked her if she remembers our conversation in my office,’ Petrov writes. ‘She assured me that she does remember it very well, and indeed had been waiting to be contacted. To that I responded that we are patient people.’

Nothing in the files is written or signed by Kristeva. It seems the authorities expected her to ‘reveal ideological centres in France that work against Bulgaria and the USSR’ and find information about other Bulgarian intellectuals and cultural figures in France, but Kristeva did not write donosi, the personal denunciations that have become a source of painful reckoning for many Bulgarians, or supply any information that could be of use to the security services. By contrast, a classmate of Kristeva’s – alias ‘Krasimir’ – submitted a report describing her as ‘very selfish’ and ‘exceptionally ambitious’, and complaining that she treated him ‘haughtily’ in Paris.

Another agent, later revealed as the writer and critic Stefan Kolarov, says he met Kristeva at La Closerie de Lilas. He asked if she had had a chance to follow developments in Bulgarian literature. She replied that she read some of the poems published in the newspapers wrapped around the jam jars her father sent her, and found them ‘despairingly weak’. ‘They lack even the smallest idea, I couldn’t find even a spark of poetry,’ she is quoted as saying in Kolarov’s six-page denunciation.

Sabina doesn’t denounce anyone. Instead, she tells the agent on her case about a colloquium on Bataille and Artaud, and explains that the left-leaning journal Politique Hebdo isn’t doing well because of its ‘provincial’ outlook. Louis Aragon is getting close to the Surrealists; he is preoccupied by the death of Elsa Triolet; he seems more distant from the PCF. Each piece of information allegedly supplied by Kristeva is accompanied by a ‘check sheet’ with a six-point grading system. Her scores are remarkably consistent: the information is invariably ‘of little value’,‘not secret’; ‘for internal use’ but never ‘confidential’; ‘credible’ and ‘timely’ but often ‘incomplete’.

Agent Lyubomirov, in charge of ‘assigning tasks’ to Sabina, reports that she ‘can be trusted’ and is ‘interesting’ but the information she provided was of little interest or use, and often already publicly available. The same pattern repeats over a handful of reports between February 1970 and December 1972. In May 1973 a decision is made to cease operational contact with Sabina because ‘she doesn’t want to work’, ‘doesn’t show up to the scheduled appointments’ and, along with her husband, has adopted ‘Maoist positions’. That she may have been too busy writing her third or fourth book, editing two magazines, working for Editions du Seuil and becoming the youngest woman to receive a professorship in France at the time, with five hundred people attending her viva in 1973, doesn’t come up in the files, or indeed in the current coverage of the allegations.

‘It’s obvious she wants her parents to come here,’ a report from June 1976 concludes, ‘but she is trying to act in a way characteristic for her – to get something from us without giving anything in return.’ Some journalists have suggested that incriminating files may be missing, but an extensive summary from 1984 concludes that Kristeva was ‘undisciplined’ and ‘excluded from the collaboration apparatus at the beginning of 1973’. After her son is born in 1976 but the authorities refuse to allow her parents to visit, she casually drops into conversation with an embassy official that Philippe may write a letter of protest to Le Monde. When the official interprets this as a threat, she is quick to attribute it instead to her husband’s ‘expansive personality and lack of understanding of the political climate in Bulgaria’.

The dossier is a fascinating document, not just for what it reveals about the crossroads at which Soviet socialism, Western European communist parties and Maoism found themselves in the 1970s, but for the remarkable personal details about Kristeva’s life and thought – even if to read about Kristeva’s doubts about ‘my new role as a housewife’, or learn that she addressed her father as ‘the father’ and sometimes used highly theoretical language even in her letters to him, can make you feel like an intruder or voyeur.

A lot of the debate in the Bulgarian media has to do with semantics: was Kristeva a ‘spy’ or an ‘agent’ or a ‘secret collaborator’? Is the documentation inconsistent or incomplete? It is very possible, according to the former member of the Dossier Commission I spoke to, that Kristeva never knew she was given the alias ‘Sabina’. It was a case name, not a pseudonym, and she never used it to sign any documents. Almost all Bulgarians who managed to leave the country were designated ‘secret collaborators’, without ever being formally drafted, trained or used. (Many of them will remain unidentified, as nearly 40 per cent of the archives were destroyed in 1990.)

As one Bulgarian journalist has noted, we are in the ‘absurd situation’ of forming an opinion of Kristeva based not on her actions ‘but on institutional assessments by State Security – an institution that we denounce as amoral and repressive but at the same time accept its criteria’.

Comments

-

3 April 2018

at

9:45pm

Timothy Rogers

says:

It’s not that hard to parse what happened here. A young, talented intellectual is called in by a communist state’s security apparatus in order to engage her services. Half a century later she is being outed as either a police informant or foreign intelligence agent – the summary of the dossier supplied by the Bulgarians doesn’t sustain either charge. From the point of view of the authorities at the time, Kristeva would naturally be a “person of interest” (due to mobility and contacts abroad), therefore a person who is requested “to do us a favor or two”, with some implication that things won’t go well for her family if she doesn’t co-operate. Not actually having rendered this service, she is viewed negatively (perhaps as a failure of the intelligence services, reflecting poorly on the state employees involved, making them malicious in their appraisal of her character). The bit of information that comes out of the succinctly reviewed dossier that is actually funny are the accusations of fellow Bulgarian members of the intelligentsia that she is “not a nice person”. No surprise there - anyone aiming to be a venerated French intellectual a la mode (whatever the current mandarin mode is) is not likely to be nice person by any conventional ascription. Too haughty, too self-involved, too ambitious, etc. – all of these characteristics are “sins” in both capitalist and socialist societies. C’est la vie, you’re going to find few intellectuals who don’t fit this bill of indictment, regardless of their political or cultural views. Let the old woman alone on this account – thoughtful criticism of her ideas is more relevant than this old dirty laundry that is not even slightly soiled.

-

4 April 2018

at

6:58pm

valyubarsky39@gmail.com

says:

I probably had been listed as an informer. Born in the USSR, I was drafted upon my graduation from a Medical School into Soviet Navy. Shortly after assuming duties as a battle ship doctor I was visited by a security service officer (GRU) for a "friendly chat". Long story short, at the end he asked me "a favour" - to report to him should I hear around unpatriotic chatter, etc. I asked "why me - I'm not a Party member", unlike all other officers on the ship. He said: "Precisely! It's even better that you're Jewish: they will be more open with you". I said "alright". Clearly, in his file I was entered as an informer or whatever.

-

4 April 2018

at

7:22pm

twlldynpobsais

says:

Perhaps the mountains of gobbledegook that Kristeva wrote through several decades were in themselves detailed secret code that contained damaging information about intellectuals in the West, especially on those who fawned upon her extravagantly and who pretended to understand the hogwash she brilliantly concocted.....

-

4 April 2018

at

10:42pm

simon edwards

says:

@

twlldynpobsais

Spot on about the Maoist hogwash (not much reflection on this in various comments in Kristeva's defence) Now we reap the consequences of this grand/grandiose 'trahison des clercs' that opened the way to the destruction of European social democracy...some shame and humility in order here!!

-

9 April 2018

at

8:21am

Dectora

says:

@

twlldynpobsais

Yes! I said yes!! Perhaps the Belgian Secret Service will now out Luce Iirigaray for crimes against the French language. I must say, my brief pre-1989 experience of Bulgaria was quite pleasant, no sense of its being a police state, I even bought my entry Visa at the border. The people seemed relatively cheerful and open and I only once once encountered the Party line from a bossy young woman who patronised me for being from the unenlightened west(Ireland).

-

9 April 2018

at

12:45pm

simon edwards

says:

@

Dectora

Exactly my first experience of Bulgaria a year later. There was some opportunist jostling among the erstwhile nomenclatura about the direction of the 'new' Bulgaria...but warm and hospitable in every other regard. After all Ireland (cf Troubles) wasnt so enlightened, no more than Thatcherite Britain....from which Bulgaria was a rather pleasant relief. Good coffee, good food, good wine, good opera, good company...

-

4 April 2018

at

8:01pm

Martin Tharp

says:

In my professional life, I work extensively with the paper unconscious, the perverted grapho-voyeur-mania, of one European Communist secret police force: its endless dust-filled mind-numbing archives. And outside the archives, I not only interview, but live among, the former watchers and the former watched.

-

4 April 2018

at

10:48pm

simon edwards

says:

@

Martin Tharp

Who are these Balkan observers who spotted the dress rehearsal for Bosnia in the 'foul regime' of Todor Zhivkov? The same regime that enabled Roma journals, closed after 1990?

-

12 April 2018

at

10:29pm

Timothy Rogers

says:

@

Martin Tharp

Kundera is an ‘interesting case’. For members of his age-group it was not unusual to be enthusiastic about the post-1948 communist government. As they saw it, Benes and his successors and ‘bourgeois democracy’ had caved in after Munich (a conference where they had no representatives, even though their country was being divvied up) by being unwilling to engage Hitler in an all-out war in the Fall of 1938. And they believed that their elders had, out of fear, been too co-operative with the Germans under the Protectorate. In other words, in their eyes their elders and elder statesmen were discredited. And they credited the Russians with ‘liberating’ Czechoslovakia, though this was sheer nonsense – at the last minute large formations of German troops bolted westward in order to avoid capture and internment by the Russians – the ‘battle for Prague’ was a series of minor skirmishes as they withdrew. One of the few members of this cohort who did not buy this version of reality was Havel, but he was sui generis. So, Kundera and his fellow-believers were keen to build socialism, even if the overall program was determined by Communists (who, for the most part, were also Stalinists). Kundera got carried away in his big, politically rhapsodic poem, which borrowed its nationalist aura from Karel Hyneks’s poem “May” (Hynek being the founding father of a revived 19th- century Czech literature, as Bozena Nemcova was its founding mother). And then the floor under him collapsed due to his ironic remarks about the Czech (and Cominform) youth-cult of Julius Fucik (all of this resulted in his very good and very autobiographical novel, ‘The Joke’). After he managed to work his way back into publishability under conditions of censorship, his novels started drifting in the direction of being implicitly more and more critical of the regime, but his other interests (in sexual adventures and misadventures) and his clever irony made them difficult to read as out-and-out assaults on the regime (though some were published abroad and in translation). And then, while various forms of dissent were brewing under the nasty “normalized” post-1968 regime (that was reactionary and culturally conservative, playing the nationalist card as well), he suddenly jumped ship and moved to France, eventually turning himself into a post-modernist novelist who began writing in French as well. To his fellow Czech writers, this was somehow ‘shameful’ (he was no longer there suffering their indignities with them). They often dragged out the message of another hallowed Czech poem (“Where is my home”) to make the point that no Czech who lived abroad, whether in exile or voluntarily, could have a real connection to Czech life and letters. But Kundera was now interested in writing to a (perhaps imaginary) ‘world literature’ standard, not specifically Czech or even Central European in its orientation and concerns. So, even though he went through a brief Stalinist phase, he himself suffered enough indignities not to be called out on this, and his writing developed in a very different direction. For the most part his early, middle, and late (French! Post-modernist!) novels are all eminently readable. Like my comments on Kristeva above, my inclination is to say, “Leave the old guy alone,” when it comes to politics. If you want to criticize his writing do it on a book-by-book basis, and make your standards more literary than political. I’ve read seven or eight of his novels (in translation) from these different phases of his life and think that they’re all better than good.

-

16 April 2018

at

11:26am

Martin Tharp

says:

@

Timothy Rogers

Thanks for a very thoughtful and stimulating response, Timothy. One quibble: the 19th-century Czech Romantic poet and author of the epic "May" was named Karel Hynek Mácha, not Karel Hynek. (There was, in fact, another poet of some standing actually named Karel Hynek, with a similarly brief and tragic life, though he was a Surrealist publishing entirely in samizdat during the worst years of the Stalinist 1950s.)

-

4 April 2018

at

9:45pm

wharfat9

says:

There is reference to the power of language. There is recognition that the Internet is going to be ´relieved´ of language. That is: back to cave dwelling .. in this case, pictures, videos. This is interesting. Men can be swayed by the voluptuousness of the visual, the written word works in almost the opposite fashion, goes in another door. You don´t have to ask Sapir-Whorf. What´s more, you can´t. We have been re-introduced to pre-prehistoric, the fenagled way. Language, of course, induces, seduces, mesmerizes ... a simple recognition of chanting where chanting is actually engaged, reveals.

-

9 April 2018

at

8:24am

Dectora

says:

@

wharfat9

What you are discussing is 'secondary orality' see Walter Ong, passim.

-

12 April 2018

at

11:23am

outofdate

says:

@

wharfat9

You mean people look more at videos now than reading?

-

5 April 2018

at

8:32am

norman rimmell

says:

As a frequent visitor to friends in Leningrad/St.Petersburg since 1957 I have no doubt I was of some interest to both the KGB, and our security services, during the Communist years. This caused no inconvenience either to myself or my friends, but the behaviour of both services was the cause of occasional amusement. I could give several examples, but will describe just one. While serving his two years national service in the Soviet army, the unit of Dima, the son of the family, was moved to Afghanistan during the Soviet occupation; prior to departure his family’s contacts with UK were discussed and it was decided that Dima should be left behind in Russia, presumably because it was considered he represented a security risk. Needless to say, Dima was quite happy with the decision.

Read moreHe'd come to see me from time to time. Most of the time I'd tell him "No, didn't hear anything." Other times I'd come up with some funny anecdote. But I myself was listening regularly to "Voice of America", which was not blocked in the Pacific, and read samizdat and talked about it with some "friends" around the ship. Finally, when my ship "Stereguschii" was about to go overseas, I got a phone call telling me to come to the base Security Office. I was met by my "visitor" together with the head of the Service. Turned out my file contained everything I said or did over entire period, they told me that I'm judged to be a security risk and potential for desertion when the ship would visit a foreign port, and as such to be dismissed from the ship. It all ended for me through "The Young Officers' Court of Honor" and dishonorable discharge. So, it's quite possible that when the Soviet Union collapsed and the GRU archives were open, someone might have read about me as an informer - at least in the first half of the file.

However there are real spooks, now retired, I found that an old friend had been a spook, he must have been the most popular agent since George Smiley and recently I found that my next door neighbour at a dinner party had been the agent in the foreign office responsible for getting Oleg Gordieksky to the UK.The dinner went with a bang after that.

As for your Irigaray observations she is in the same boat as Kristeva...?

As a result, I would like merely to suggest that historiographic categories of micro- and macro- scales, of titanic ethical questions and the most loathsome personal grudges, were thrown into an endless confusion in European Communist practice. Disputes of an almost unspeakably petty smallness could end up cast into grandiose world-historical terms once they came into police surveillance. Any secret-police file, as a result, deserves to be treated with the hermeneutics of radical suspicion: not to be seen as gospel, not to be rejected outright, but to be interrogated, in Carlo Ginzberg's sense. Kristeva's file, at least from its display on the present blog post, seems to be a genuine fabrication (ah that deliciously evil postmodernism of the Bolsheviks!) - there is no evidence of betrayal of a specific individual to the forces of repression. The contrast with Milan Kundera's secret-police informing (where we know the clear identity of his victim and his cruel sentence to the uranium mines) is striking. (Not of course to mention Kundera's own fervent Stalinism and wretched Stalinist versifying throughout the 1950s, which are matters of open public record.)

But there is a third matter to keep in mind: cui bono? Who is benefiting from the release of this information in Bulgaria today? All across post-Communist Europe, it is possible to discern not merely the dismantling of the 1990s open society, but even more worryingly, the emergence of a "red-brown" coalition between old Communists, Generation X rightists, and Pepe-meme-addicted millenials - all around the flag of nationalism and national purity. In Bulgaria, the foul regime of Todor Zhivkov is increasingly praised for the vicious anti-Turkish measures implemented at the end of the 1980s, rightly regarded by some Balkan observers as a dress rehearsal for Bosnia less than a decade later. An attack on a Western intellectual, and a leading defender of social openness at that, could definitely be interpreted as a disturbing attempt to split up the pro-Western forces as Bulgaria's xenophobia only swells in strength.

However, I feel that I should say that my point about Milan Kundera was less about his literary, intellectual or political legacies than about the strong evidence that he 1) willingly volunteered to supply information to the Czechoslovak secret police and 2) caused very real harm to a specific individual, Miroslav Dlask, sentenced to the Jáchymov uranium mines for espionage on the basis of the information that (it seems) Kundera supplied. By contrast, there is absolutely nothing in Kristeva's file that even slightly suggests her contact with the Bulgarian secret police ever harmed anyone.