Pakistan, Polio and the CIA

Jonathan Kennedy

In the mid-20th century, poliovirus paralysed half a million children a year, in rich countries as well as poor. In 1952 there were 57,628 cases in the United States. Following the development of vaccines by Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin, polio declined markedly in North America and Europe. The US had its last case in 1979, the UK in 1982.

There were still, however, about 350,000 cases a year in the mid-1980s, predominantly in countries where the state did not have the money or capacity to implement mass vaccination programmes. The Global Polio Eradication Initiative was formed in 1988 by the WHO and national governments to finance and organise immunisation campaigns. It precipitated a sharp reduction in polio: there were 37 cases in the world in 2016, a fall of 99.9 per cent.

But the disease stubbornly persists in Nigeria, Afghanistan and Pakistan. By the mid-2000s, Pakistan had almost eradicated polio: there were only 28 cases in 2005, 1.4 per cent of the global total. But there have been 380 in the last three years, 81 per cent of polio cases worldwide. More than half of them were in the semi-autonomous Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of northwest Pakistan, where only 2 per cent of the population live.

After the invasion of Afghanistan by American-led forces in 2001, many Taliban fighters relocated to the FATA, from where they launched cross-border attacks. The Pakistani army tried to bring the region under government control but the incursion aggrieved local communities, who joined forces with the militants. The CIA used drone strikes to support Pakistani military action from 2004 onwards. According to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, there have been 428 drone strikes, leading to between 2511 and 4020 fatalities.

Vaccination campaigns were suspected of being a smokescreen for collecting intelligence ahead of drone strikes. Organisations involved in the Pakistan Polio Eradication Initiative include the Pakistani state and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Polio vaccinators visit the FATA every few months, walking from door-to-door, offering to vaccinate children, and recording who has been vaccinated. The data is collected for public health purposes, but you can see how it might be misconstrued as intelligence gathering.

There have also been complaints that ‘billions of dollars’ are spent on vaccination campaigns when ‘polio infects one child in a million’, while malnutrition and diarrhoea receive far less attention from the international community despite causing much more suffering. Polio workers have been attacked and vaccination campaigns interrupted, reducing the number of children being immunised and leading to an increase in polio cases.

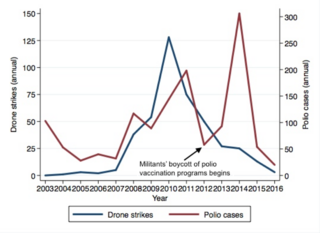

Between 2004 and 2012, the numbers of drone strikes and polio cases corresponded closely. Until mid-2008, the US carried out a small number of drone strikes to assist Pakistani military operations and there were relatively few polio cases. From mid-2008, the number of drones strikes increased rapidly, peaking in 2010 at 128. The number of polio cases also rose markedly, reaching 198 cases the following year. Drone strikes were reduced after 2012 because of concerns they were destabilising Pakistan and generating anti-American sentiment. Polio also decreased rapidly between 2011 and 2012.

But it increased sharply from 2012, hitting 306 cases in 2014. Before the assassination of Osama bin Laden in May 2011, the CIA organised a fake hepatitis B vaccination campaign in Abbottabad in a failed attempt to obtain his relatives’ DNA. When the story broke a few months later, it seemed to vindicate people’s suspicions of the polio programmes in the FATA. ‘As long as drone strikes are not stopped in Waziristan,’one militant leader declared, ‘there will be a ban on administering polio jabs’ because immunisation campaigns are ‘used to spy for America against the Mujahideen’. More than 3.5 million children went unvaccinated as a result of the boycott and associated disruption, in which several health workers were killed. Polio increased in Pakistan and further afield, as the virus spread to Afghanistan and the Middle East.

The CIA have conducted only a handful of drone strikes in Pakistan in recent years and polio is now at an all-time low. But the plan to eradicate the disease may face further setbacks. ‘We can no longer be silent,’ President Trump said last month, ‘about Pakistan’s safe havens for terrorist organisations, the Taliban and other groups that pose a threat to the region and beyond.’