Raw Material

Adam Shatz · Dana Schutz’s ‘Open Casket’

In 1989, John Ahearn, a white artist living in the South Bronx, cast a group of local black and Latino people for a series of bronze sculptures commissioned by the city for an intersection outside a police station. As his models, he chose a drug addict, a hustler and a street kid. Ahearn thought that he was paying them homage, restoring the humanity of people who were often vilified in American society. His models found the work flattering, but some members of the community felt that he ought to have depicted more 'positive' representatives, while others were insulted that a white artist had been given such a commission in the first place, since only a genuine local – a black or Latino artist – had the right to represent the community. Ahearn eventually removed the sculptures. 'The issues were too hot for dialogue,' he reflected later. 'The critics said that people in the community have a right to positive images that their children can look up to. I agree that the installation did not serve that purpose.'

Jane Kramer wrote about Ahearn in the New Yorker, and later expanded her piece into a short book, Whose Art Is It? I was reminded of Kramer's book, and the questions it raises about the frictions between artistic freedom and cultural ownership, by the controversy surrounding the work of another white artist, Dana Schutz's Open Casket, a painting based on the iconic photographs of Emmett Till in his coffin. Emmett Till was a 14-year-old boy lynched in Mississippi in 1955 for allegedly flirting with a white woman; his killers were acquitted. His mother insisted on the photographs of his body being published as evidence of the horror inflicted on her son. Schutz's painting, on display at the Whitney Biennial, has raised accusations of racially insensitive exploitation, and prompted a silent protest at the museum, as well as a petition that the work be removed and even destroyed.

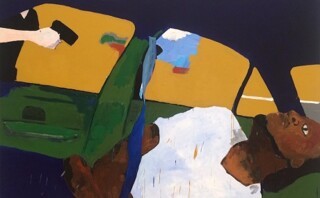

Schutz's critics accuse her, first, of aestheticising atrocity in an offensive and insensitive way. 'Where the photographs stood for a plain and universal photographic truth,' Josephine Livingstone and Lovia Gyarkye argue in the New Republic, 'Schutz has blurred the reality of Till’s death, infusing it with subjectivity.' But 'aestheticise' is precisely what painters can't help but do when they paint from photographs; think of Gerhard Richter's paintings of the Baader-Meinhof terrorists who died in police custody, or of Picasso's Guernica. It may be impossible for a painting of an atrocity not to 'aestheticise' horror. The charge could be levelled at a painting of another racist atrocity at the Whitney Biennial, Henry Taylor's depiction of the death of Philando Castile, who was killed in his car by a Minnesota police officer last July. But Taylor, unlike Schutz, is black.

This is where the second claim comes in: that white artists, whatever their intentions (or whatever they imagine to be their intentions), are engaging in illegitimate cultural appropriation when they depict black suffering. (Richter and Picasso, on this view, were exercising their right to paint their own people.) Hannah Black, a British-born black artist who lives in Berlin, wrote an open letter to the Whitney that has attracted signatures from a number of young artists of colour:

Although Schutz’s intention may be to present white shame, this shame is not correctly represented as a painting of a dead Black boy by a white artist – those non-Black artists who sincerely wish to highlight the shameful nature of white violence should first of all stop treating Black pain as raw material. The subject matter is not Schutz’s; white free speech and white creative freedom have been founded on the constraint of others, and are not natural rights. The painting must go.

On this view, Schutz's work is objectively complicit with racism, even in its protest against racism, because the mere fact of a white artist representing a mutilated black body, and using it as 'raw material', is predicated on white supremacy.

This is not the sort of debate that the biennial’s curators, Mia Locks and Christopher Y. Lew, were hoping to spark. Few artists have come to Schutz's defence, even if they privately disagree with the protest. (Kara Walker, whose provocative imaginings of plantation life initially provoked an uproar among some older black artists, published an eloquent statement in support of Schutz.) When white standards of beauty and aesthetics have been the norm for centuries – and against the backdrop of police killings of young black men – the traditional free speech principle that an artist has the right to choose her material can hardly compete with the critique of the use of the black body as white material. Seldom has the charge of cultural appropriation stung so sharply in liberal circles. White fascination with black culture turns to gruesome intellectual property theft in Jordan Peele's brilliant new horror film, Get Out, whose villains kidnap black people to steal their brains. 'I want your eyes, man,' one of the perpetrators, a seeming liberal, says to a young black man. 'I want those things you see through.'

Schutz makes no claim to see Till through black eyes. In her response to the protest letter, she said plainly that she has no way of understanding 'what it is like to be black in America', which can be read either as a disarming expression of humility, or (less charitably) as a failure of imagination. But she has otherwise deferred to the terms of the debate set by the protesters, who argue that experience, if not identity itself, confers the right of representation. As a mother, Schutz says, she can imagine the pain of Mamie Till Mobley, who lost her 14-year-old son, and is therefore qualified to use this image to create a 'space for empathy'. The effect of her comment was to assert a right to represent rooted in personal experience, and to further particularise suffering. But black history – as W.E.B. Du Bois and James Baldwin, among others, always stressed – is American history; confronting it a common burden.

The photographs of Emmett Till are to the memory of lynching what pictures of Anne Frank are to the memory of the Holocaust. It is, in other words, almost sacred, and any attempt to represent it was bound to strike some people as blasphemous. The argument that his image should not be aestheticised is similar to the argument that the Holocaust should not be visually depicted. Claude Lanzmann's film Shoah (1985) included not a single newsreel image. Lanzmann's argument no longer enjoys the authority it once did. Shoah was followed by Spielberg's Schindler's List, and later by Tarantino's Inglourious Basterds, which retold the Occupation of France as a spaghetti Western. But the sensitivities around the representation of racist atrocities – and, more broadly, black bodies – run much higher than those around the Holocaust, precisely because they have not come to an end. Emmett Till in his coffin evokes contemporary police violence and mass incarceration, the New Jim Crow, as much as it does the era of Jim Crow.

This does not, however, resolve the question that Jane Kramer posed in her book about John Ahearn: whose art is it, and who gets to make it? A prominent black curator told me years ago about a tour she had given to a group of people visiting a show of work about race in America. A black woman in the group pointed to a painting she considered degrading to black people, and compared it to one that, in her view, expressed an ennobling vision of black humanity. The first painting was by Robert Colescott, a black artist who has drawn mischievously on African-American stereotypes in his work; the second was by the white, Jewish artist Leon Golub, a left-wing figurative painter. It could be argued that one painter was exercising his cultural rights, the other mining the black body for raw material. But for at least one black viewer, the question of whether belonging confers legitimacy was not so easily settled.

What is most troubling about the call to remove Schutz's painting is not the censoriousness, but the implicit disavowal that acts of radical sympathy, and imaginative identification, are possible across racial lines. Edward Said, writing of the erasure of Palestinian history, regretted that Palestinians were denied 'permission to narrate', and insisted that Palestinians had to tell their own story, and foist it on the world's consciousness. But he always welcomed the efforts of anti-Zionist Jewish and Israeli writers to contribute to this story, because he knew it was an indivisible Arab-Jewish one. Truth for Said was 'contrapuntal', not a monologue. Perhaps, in the juxtaposition of Dana Schutz's Open Casket and Henry Taylor's painting of Philando Castile, the Whitney Biennial is making a small contribution to the telling of America's contrapuntal racial history.

Comments

-

24 March 2017

at

4:12pm

ssandberg

says:

Like many artists, I struggle with questions like these about what subject matter one is "allowed" to use, especially when one wants to be an ally or create works, as Shatz says, of "radical sympathy." I think trying to excuse the painting based on America's racial history being a "common burden" flattens out the asymmetrical and still violent racial dynamics too much. It's a common burden but only one side suffers the devastating consequences and therefore it seems selfish — and/or staking an insensitive claim for art as an amoral and purely aesthetic/theoretical space — to not just accept that as a white painter one should demure and leave certain subjects alone. There are plenty of things to base your works of "radical sympathy" on that don't stray into the questionable territory of "Open Casket."

-

24 March 2017

at

6:09pm

whisperit

says:

@

ssandberg

I'd suggest that it isn't "only one side [that] suffers the devastating consequences" of oppression. The consequences may be highly asymmetric, but doesn't racism - for example - diminish all of us, doesn't it attack the core of our common humanity? If that is the case, then artists (by which I mean all of us) are surely entitled to respond to this attack, albeit each from their particular perspective and location.

-

28 March 2017

at

3:12am

mephisto

says:

@

whisperit

"Highly asymmetric" is an extremely poor choice of words as well as one of the biggest understatements I've seen in some time. It also reflects a certain kind of white privilege in more telling terms than the painting in question.

-

24 March 2017

at

6:08pm

Lowellk

says:

As an artist and teacher, I'm constantly perplexed by the notion of what is and what is not appropriate for an artist to choose as a subject. What is a controversy or now what is a 'fake' controversy. This subject has serious tones of how we see each other, how we reflect on the issues that are current in our lives.

-

28 March 2017

at

3:40am

mephisto

says:

@

Lowellk

What is interesting about responses like this which I've heard echoed among many let us say well-intentioned white people is that the much of the "falseness" in this "controversy" stems directly from this compulsive flight into impassioned defense of censorship and the inalienable rights of artists.

-

29 March 2017

at

12:33am

robin bale

says:

@

mephisto

You're right.

-

25 March 2017

at

12:59am

danglard

says:

I couldn't disagree more vehemently with this entire piece (for example, that the painting isn't appropriating black eyes a la Get Out when the photo was taken for a black publication after a black mother insisted people see what she saw with an open casket). But formal/historical disagreements aside, it also really marks the limitations of a certain kind of formalist criticism that takes the subject matter for granted and then asks questions *not even* how about the choice of subject matter is being contested formally by the artist (because, of course, it's not, as in Richter or Picasso), but rather of what the artist has done with the subject matter. Important stuff only by ignoring the first thing the artist has done, which is choose this subject matter at all. But I also hate the painting and hate the premise that the photo needed to be re-represented (the aesthetic equivalent of whitesplaining a photo from a black community all to exculpate the artist's sense of racism even while justifying it?).

-

25 March 2017

at

12:19pm

kirstamb

says:

I think part of what makes Open Casket distasteful, which has not been commented on here, is the very specific nature of the original photograph and the choice of the open casket funeral. These were visual means through which Mamie Till-Mobley sought to control the interpretation of what happened to her son ('I want them to see what I see') and what that mutilated Black body meant. In that context, Schultz's painting represents a White woman offering her own subjective lens on an image that a Black woman had previously sought to control. It's hard to see how that can be anything other than appropriation, and the plea of common motherhood seems similarly blind to its privilege: Black motherhood has historically been highly charged in a way that White motherhood has not. That's why it's important to see the painting in the context of its putative relationship between two women which is constituted within two very different experiences of race.

-

25 March 2017

at

4:16pm

MindTheGap

says:

Whether or not Dana Schutz's painting is a good painting is eminently worthy of debate, but the claim -- if that is claim Hannah Black is making -- that in principle no white artist has the right -- the moral standing -- to respond to the photograph of Emmett Til in his open casket amounts to a cultural miscengenation proscription. Does simply being white -- or Asian or Hispanic -- deny me the moral standing to be addressed by Mamie Till Mobley's brave exhortation "Let the people see what I see"? Should I, being white, not rather be exhorted to assume that moral standing? Should I not see and have my ways of seeing changed by what I see? Who do we want "the people" to be?

-

29 March 2017

at

1:02am

robin bale

says:

@

MindTheGap

Who we want "the people" to be, or who is recognised as "the people" is the prevalent political question for some many years now (see Brexit for the most recent instantiation). I suppose the vulgar (and proved to be efficacious) answer is "if you have to ask, it isn't you". Of course, it's no actual answer. There is no actual, intellectually satisfying, answer.

-

26 March 2017

at

8:59am

Parissing

says:

My European vantage must have spoiled me. From appeals to an unquestionable moral authority and the various congregational amens known as virtue signaling, I really don't see anything new here: banning something you don't like is as old as the hills in the States. Am I the only person who finds the idea that an exhibition of new art should provide, in some mysterious but all seeing way, protection from distaste, dislike, discomfort laughable? I lived in New York for forty years. Usually the campaigns went the other way: to get work seen.

-

26 March 2017

at

3:03pm

Locus

says:

@

Parissing

Yes. Calls for the image's destruction have managed to disseminate the image extremely successfully. Apart from anything else, the controversy can be indexed under "Streisand Effect, further examples of."

-

26 March 2017

at

9:06pm

prwhalley

says:

@

Parissing

Why is the idea that "it was also quite possible for Schutz not to paint this painting,” so cringe-worthy? Nothing wrong with a bit of self-restraint (or cultural common-sense). The artist could've had the idea to make the painting and then, a few minutes later, thought "Nah. That's a dumb idea. I'll paint something else".

-

26 March 2017

at

6:17pm

Parissing

says:

But, Locus, upon further reflection, that isn't precisely what they wanted to do, was it? Just have the image removed from the show? What they wanted was to hound this artist out of the show, shame her and set an example for others. THEY in some mysterious way - by dint of their outrage over a painting - own the images of Emmet Till, all while affecting the manner of someone under attack.

-

26 March 2017

at

7:06pm

Locus

says:

@

Parissing

Yes, you are generally right: amplified publicity is in that sense the medium the critics use for their various purposes. But alongside that, there is also a irony in the picture being faithfully reproduced in every single article reporting on calls for its suppression.

-

27 March 2017

at

4:19pm

charrchr

says:

I love her work, but Dana Schultz went for the low hanging fruit on this piece and "assuming " viewers would get the "Mother" connection is asking too much. It's the weak idea of concept-switching on the back of a tragic cultural event masking as fine art is what bugs me (Richard Prince). White guilt at table one, please! She has and can do conceptually stronger art that is original and more thought-provoking. Right now now it looks like an exercise in exploitation and wrong-headed appropriation. This smells like sensationalism on her part and the Whitney. Shame on the Whitney and its curators. Maybe some more pre-show crits with Black folks could have helped!!! As a African American male artist, I think all ideas and perspectives from any viewpoint are fair game, as long as it's clear in its intent and this painting is not. Destroying the piece is extremist bullshit that smacks of censorship. Do artists want to start doing that to ourselves now? It's bad enough non-artists try to do that! Creative folk do, should and need to be canaries in the coal mines of society to keep humanity honest, but be smart enough to look at all sides of an idea to make sure it passes the smell test which if not handled correctly can harm more than help the message. I suggest Schultz sell the work and donate the proceeds to a civil rights group and paint with a wiser, more consciously creative brush going forward.

-

27 March 2017

at

6:18pm

jcl

says:

We did not need a debate about (nonexistent) censorship - We need a conversation about what kinds of acts are effective for becoming an accomplice in the fight for racial justice and what kinds of actions (tho well intended) contribute to the problem.

-

28 March 2017

at

5:49pm

John Cowan

says:

Let's not forget that Gernika was and is a Basque town and Picasso was no Basque. I live in Manhattan: if I go take pictures in the Bronx, is that cultural appropriation?

-

29 March 2017

at

11:08am

immaculate

says:

@

John Cowan

"Let’s not forget that Gernika was and is a Basque town and Picasso was no Basque."

-

29 March 2017

at

2:20pm

Chrisdf

says:

Should we ban authors from writing about certain subjects without having gathered the right credentials from the appropriate (self-constituted?) authorities? I don't think so. I do however feel that it would have have been tactful to discuss the project with the Till family in the first place. Artists can be crass. However, I also think that the spectre of nihilist hatred directed against black Americans once again stalks the US political stage, and it's right that it should be put in the spotlight for the world to see--and fear, as we should.

-

29 March 2017

at

2:22pm

Chrisdf

says:

Should we ban authors from writing about certain subjects without having gathered the right credentials from the appropriate (self-constituted?) authorities? I don't think so. I do however feel that it would have have been tactful to discuss the project with the Till family in the first place. Artists can be crass.

-

29 March 2017

at

2:31pm

Chrisdf

says:

Nevertheless, wherever we are, we ought to recognise, and fear, the rise of hatred directed towards black Americans in particular which has now re-entered the American political stage. It really does concern us all.

-

29 March 2017

at

10:45pm

trishjw

says:

Why can't others talk of Till via paintings etc if most of the journalism written about his death, his mother's actions, and black history in general have mostly been done by white journalists?? Granted there were and still are very few black journalists but why would that close it out??? Black history of all kinds and literature were first done by whites to illustrate the evils of slavery and racial prejudice--separately or together. Why can't the same be done in painting? If white writers and artists hadn't written and taken pictures of slavery or of Holocaust we all would be much less informed of either subject. If individuals don't like her paintings of Till, don't look at them. But don't demand that they be taken down so others can't see them and judge for themselves. This goes for any kind of art.

Read moreAll that said, what is often missing from the discussion around this painting seems to be attention to the work itself, its manner of depiction, which seems the most important thing of all, for that is where the painting's relationship to its subject matter is truly located and, I think, a major part of why it has caused such controversy. Josephine Livingstone and Lovia Gyarkye make some excellent observations in their article and good points about Schutz's style and approach. I think perhaps the key problem is that Schutz's cubist-inspired distortions of form and volume simply cannot differentiate the mutilated head of Emmett Till from any other head she paints. The distortions in her painting are too general (even generic), too exactly in line with her other works, so that we can no longer trace them back to the original violence against Till, but they instead become the kind of formal violence standard of Schutz. The specificity of the original horror is lost and Till becomes just another subject on display, and our viewing, therefore, returns to a standard aesthetic consideration of painterly moves.

I think Shatz's story about Colescott and Golub, rather than complicating the issue of who's "allowed" to depict what, underlines the importance of considering the works as they function themselves, how they represent the subject matter, rather than letting who made them be the last word. What makes Henry Taylor's painting more successful than Schutz's is not simply the fact that he's a black artist, but how his more direct approach better preserves and represents the specificity of the violence depicted. His painting does not so overbearingly subsume the image of a dead black body into the formal dialogue of post-cubist figurative painting.

Finally, it is worth remembering one of the other paintings by Schutz included in the Whitney, "Shame", which depicts a white figure — without gender, but the pose of the figure wading in the water reminds me of Rembrandt's "Woman Bathing in a Stream" in London. Given the controversy, taking these two paintings together produces a noteworthy, perhaps intended, "contrapuntal" tension.

The idea that, for example, the murder of a person of color by law enforcement in some large part because of their color and an extensive, perverted cultural history can be equated with the bad conscience of a non-minority clearly demonstrates an obliviousness whose often earnest desire to "understand" is completely contradicted and unraveled by its efforts to do so.

How could you possibly "understand" or "share" some common "diminishment" when you glibly cast away the importance, value, and the actual human toll - death, anguish, misery - of those who most directly and painfully suffer?

The amusing part of this is to imagine someone like Mr. Bosley telling a Holocaust survivor that although the consequences were asymmetric, we all are diminished by what happened. First because it would never ever actually happen and second because opprobrium would be swift and sure.

But of course white people who feel perfectly at home trying to "share" the suffering of people of color would never have the chutzpah to claim Jewish suffering as in some part their own...

Consider Bertolt Brecht's The Caucasian Chalk Circle: A German writer, living at the time in the U.S. revives an earlier story of his derived from a Chinese story and sets this play in the Soviet Union. Is this a relevant comparison? Let's consider the community response to the work of Gu Wenda and his exhibition that focused on the menstrual cycle of women and their 'gifts' - used tampons - and letters he requested from women on what the menstrual cycle meant to them. For Gu Wenda, the menstrual cycle was a forbidden subject in China. For a group of women is San Francisco, the controversy was why was a man handling the subject.

Many years ago I was asked by the director of the Mission Cultural Center to apply for a grant from the California Arts Council to teach a theater course at the Center for the youth in the community. I was denied by the CAC because I was white. I understood that. Three years later they had a wonderful program of Hispanic artists teaching Hispanic kids in the community. It is relevant to build programs where those in the community who understand them and their voices teach the kids.

Schutz is not painting outside of what is relevant in her life. Denying an artist a voice is censorship, plain a simple. Carson McCullers created a deaf character in her book The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. Her mother asked her what she knew about deaf people, concerned that this was not an appropriate character for her to create. Carson said, "Imagination is truer than reality." The imagination of the artist must stay free to express and to explore.

Protesting the artist and her work does not do justice to the issue of violence against the Black community. An artist who is a woman and who is white has the creative power to express in her own experience how this issue has affected her from her perspective. She lives in this society and this issue has affected us all, across the racial spectrum. You can judge the painting for it's artistic merit all you want, and you can analyze the social issues around a white woman expressing this tragedy that occurred to this Black family, community and the nation. We cannot censor artist and say you can only express this point of view or censor a gallery and say that they have to censor artists because of some bias.

Her work is about a national if not world struggle that we are trying to understand. Her view is relevant to her, and I must say to us all because she is taking on this issue, putting emphasis on this moment in time for us all to take another look and not to forget. She is not speaking for Black people. She doesn't appear to be speaking for Black people. Schutz expresses her own thoughts on a controversial and sad story in American history. And she has all the right to do so. It's a shame that the artist has been forced to submit to this less than honest attack by removing her work for sale. Selling her work, as she has the right to do, is not making money off of anyone. It is making money off of her experience, her vision, and her artistic expression. Her work is honest from her perspective. Let’s move on.

One can choose to see in this as a censorship issue, but let us be clear - the only people who can censor this piece are the curators and the Whitney.

Everyone else including those poor souls who are calling for its destruction are exercising their rights to criticize the piece - rights that they are just as entitled to as the artist is entitled to her expression.

Yet never do I find a single passage in one of these manifestos for artistic freedom that acknowledges that the artist's critics are equally entitled to their unfettered opinions - in whatever way they see fit to express them within the bounds of the law.

An artist can create whatever they like - but they also can - and should have to deal with the ramifications of that creation, whether pleasant or not.

This artist must have known that appropriating this photo was going to provoke some negative reaction (if not she is either extremely naive or utterly ignorant about African American culture). She decided to show it regardless. What happens after that is the price of the ticket for artistic freedom.

Making this into a censorship issue merely allows people to avoid truly difficult painful questions about art, appropriation, exploitation, and racism that cannot be resolved by idealistic abstractions about artistic freedom.

There would never have been this argument about the painting if it were not shown in the Whitney. It could have cropped up elsewhere and probably been unnoticed. It wouldn't have made it any better as an idea, or as a painting, but it wouldn't have caused such waves.

I don't live in New York, I live in London where there is a myriad of smaller galleries where this could have been shown - and no one would have noticed or commented on a piece of sub-cubist via Bacon stuff. To be honest, the subject matter would have impinged on virtually no one, because no one would have been looking that way. Or, and I think that this is crucial, have a nice catalog in their hands telling them how to look, or what to look for. That doesn't mean that I'm saying that the painting is good, as a painting (I don't think that it is) or well-advised (obviously not).

However, whilst I think that Schutz should take her critical lumps, those who chose and metaphorically framed her painting are the ones responsible, in a wider sense. Just as the artist did, they have shown a tin ear, or a tone-deaf sense of solidarity. In other words; blame the artist, for sure, but blame the curators - therefore the institution and institutional structure -considerably more, for including it and thinking that, somehow, it would be OK.

"But ‘aestheticise’ is precisely what painters can’t help but do when they paint from photographs; think of Gerhard Richter’s paintings of the Baader-Meinhof terrorists who died in police custody, or of Picasso’s Guernica. It may be impossible for a painting of an atrocity not to ‘aestheticise’ horror."

It certainly is impossible. But it was also quite possible for Schutz not to paint this painting, though the terms are constructed to make us think she couldn't "help but do" otherwise.

The point remains, however, that whoever "the people" are, Mamie Till Mobley probably didn't mean that they should see a sub-cubist-by-way-of-Bacon representation. She meant either the the open coffin, or the photographs. It is another, separate and also useful, debate whether the photograph necessarily is more useful as a conduit between open and systemic violence and "the people" than a highly stylised painting (whilst recognising that photography will also always have "style", one way or another).

The authors of the various jeremiads employ the heavy tropes of impenetrable art-world jargon (impenetrable in the sense of protected from either normal discourse or criticism) but having watched this virtuous tirade more than once before, I can't escape the feeling it has something to do with their unexamined outrage and some other part with getting noticed themselves. Well, ain't that the hustle!

Those who propose banning Dana Schutz's work don't seem to realize how antiquated their efforts are: it really isn't possible to ban images any more. While some of the arguments above I find amusing in their moral certainties - and that is the business they traffic in - I find Dangland's statement, "But it was also quite possible for Schutz not to paint this painting," cringe-worthy. It's but one step from there, Commissar, to a Bureau of Sensitivities which will pay visits to artist's studios. All this for a work that began as an act of solidarity.

If #SchutzGate was intended to be an allied voice - I suspect that it was - and that aspect of the work failed ~ The most important question becomes: How should privileged voices respond when their good intentions do not succeed?

The institutional response leans on the individual's freedom of expression - while defensible, it ignores how institutional inequality perpetuates structural racism and marginalizies the voices of black artists.

In this way, art institutions effectively deny that freedom of expression to whole spectrums of the American experience. The only real censorship at issue here is the censorship of exclusion.

It gets worse than that, I'm afraid. Picasso was a man and he painted women. Sometimes French women, to boot. Appropriation or what? And fruit. And guitars. And bulls. There's no end to the man's appropriating.

So why don't we just have lots of separate museums? You know, a museum of works by white Spanish men of other white Spanish men (and so on). Then nobody can be offended, can they? Might be a shortage of still lifes, until guitars and apples learn to paint, but that's surely a small price to pay.

And in passing, since being offended seems to be the new order, I'm more than a little offended by some people (of whatever race, age or gender) telling others what they're allowed to paint or not, and look at or not, and read or not, and imagine or not, and think or not, as a result of their race, age or gender.

And, on a different note, the idea that there is some kind of "plain and universal photographic truth" represented in photographs is in need of some serious re-thinking. In my opinion.