Another Name for Rock and Roll

Alex Abramovich

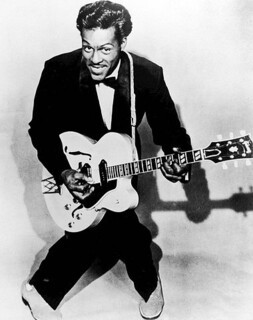

Every year, at around this time, the radio station WFMU hosts a fundraising marathon. The highlight is usually Yo La Tengo’s marathon-within-a-marathon covers session, which lasts for three hours or so. Callers who pledge a hundred dollars get to request a song – any song. YLT do their best to play it. Most of the time, there are too many songs to get to, and so, as the mini-marathon draws to its close, the band does an extended medley. On Saturday, YLT set that medley to the tune of the Velvet Underground’s ‘Sister Ray’. Midway through, they sang a good portion of Chuck Berry’s mysterious ‘Memphis, Tennessee’. Weirdly, the words fit the tune perfectly. But then I was reminded of Berry’s response, in 1980, to recordings by Wire, Joy Division and the Sex Pistols. ‘So this is the so-called new stuff,’ Berry said. ‘It’s nothing I ain’t heard before. It sounds like an old blues jam that BB and Muddy would carry on backstage at the old amphitheatre in Chicago. The instruments may be different but the experiment’s the same.’ An hour later, a friend called to tell me that Berry was dead.

Charles Edward Anderson Berry got his start working odd jobs and playing backyard parties and juke joints in East St Louis, and ended up at a club called the Cosmopolitan. ‘The music played most around St Louis was country-western, which was usually called hillbilly music, and swing,’ he wrote in his autobiography.

Curiosity provoked me to lay a lot of the country stuff on our predominantly black audience and some of the clubgoers started whispering: ‘Who is that black hillbilly at the Cosmo?’ After they laughed at me a few times, they began requesting the hillbilly stuff and enjoyed trying to dance to it. If you ever want to see something that is far out, watch a crowd of coloured folk, half high, wholeheartedly doing the hoedown barefooted.

A local guitarist had told Berry that 80 per cent of the popular songs out there were based on the chords to George Gershwin’s ‘I Got Rhythm’. So Berry learned enough chords to play ‘almost 80 per cent’ of the songs he had heard. ‘I worked until I had matched over ninety popular songs together with their lyrics and began to sing them before people as often as I had the opportunity,’ he said. ‘I even took the guitar on dates and sang to the girl I’d be with.’

That attention to detail served Berry well when he turned his hand to songwriting – smart and systematic, he plugged every possible variable into the equations at hand and wrote anthems that were reverse-engineered to appeal to rock and roll’s core constituency of disaffected teenagers.

The songs were ‘intended to have a wide scope of interest to the general public rather than a rare or particular incidental occurrence that would entreat the memory of only a few’, Berry said. But the lyrics were fine-grained and cinematic. Berry’s sweet little sixteen-year-olds carried ‘wallets filled with pictures’, and his teenage newlyweds crammed their iceboxes with ‘TV dinners and ginger ales’. His country folks lived in log cabins ‘made of earth and wood’ and drank their moonshine ‘from a wooden cup’. Berry is celebrated for his neologisms: ‘botherations’ and ‘coolerators’ (in ‘Memphis, Tennessee’, tears are ‘hurry home drops’). But his images and similes are just as impressive, and his sense of control is startling: when Berry shouts to the city bus driver – ‘Hey conductor, you must … slow down!’ – the song slows with him.

Berry’s first single, ‘Maybellene’, was loosely based on a country song (‘Ida Red’ by Bob Wills), set against a two-beat country rhythm. It came out, and crossed over, in the summer of 1955; for the next five years Berry wrote one classic after another, and musicians climbed over each other to cover him. The Rolling Stones announced themselves with ‘Carol’ and their first single, ‘Come On’ (which sounded uncannily like a Rolling Stones song already). The Beatles staked out ‘Rock and Roll Music’ and ‘Roll Over, Beethoven’. ‘If you tried to give rock and roll another name,’ John Lennon said, ‘you might call it “Chuck Berry”.’ And while Bob Dylan claimed Little Richard as his role model, his three-stroke character sketches, his sense of humour and his maniacal, machine-gun approach owed everything to Berry. (Listen to ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’ next to Berry’s ‘Too Much Monkey Business’.) Berry’s ‘You Can’t Catch Me’ is father to ‘Come Together’ by the Beatles, ‘1970’ by the Stooges and two songs (‘State Trooper’ and ‘Open All Night’) on Bruce Springsteen’s best album, Nebraska.

Berry drafted and redrafted, relentlessly, and polished his songs to a high sheen. Of ‘Johnny B. Goode’ he said: ‘My first thought was to make his life follow as my own had come along, but I thought it would seem biased to white fans to say “coloured boy,” and changed it to “country boy”.’ ‘School Days’ started out as the less-inclusive ‘Teenage Days’. ‘Sweet Little Sixteen’ referenced Pittsburgh, Texas, San Francisco, St Louis, New Orleans and Philadelphia because he knew that shouting out place names was a good way of getting his songs played in those places. Like Wallace Stevens, Chuck Berry was a poet-actuary.

By most accounts, he was a hard-nosed, cynical man. For most of his career he travelled solo and played with whomever he was paired with. (The way Berry figured it, more or less correctly, every band knew all of his songs already.) The concert promoter Bill Graham described a typical encounter in his memoir:

There was a knock on the door. I opened it and there was Chuck Berry. I shook his hand. I said: ‘How you doing Chuck? You’re a little late.’

He didn’t move or speak. He set his guitar case down on the floor and stood there staring at me. ‘Right,’ I said. ‘You want to get paid before you go on.’

I went in and got the chequebook. Some bands would take a cheque and deposit it. Others wanted the cheque cashed right then and there. I made the mistake of looking over at Chuck Berry and saying: ‘You want cash or a cheque?’ The look he gave me was: ‘Are you out of your mind? Why do you ask such a stupid question? I won’t even honour it with an answer.’

‘OK,’ I said. I took the cheque, wrote it out, and moved it over to his side of the desk.

He signed the cheque on the back. Then he moved it halfway over toward me. Like into the medium, neutral zone of the desk. He still hadn’t said a word. I pushed $800 in cash over to his side of the desk. He counted it out in front of me. He took the money in one hand, slid the cheque all the way over to me, and put out his other hand for me to shake.

‘Mellow,’ he said.

I took the signed cheque and stuck it in my pocket. He put down his coat and unpacked his guitar. I said: ‘Chuck, are you ready?’ I thought he would say: ‘I gotta go to the bathroom. I gotta change my shoes or my shirt.’ He said: ‘Let’s go.’ It was like: ‘You want me to fight ten rounds? I’ll fight ten.’

He walked onto the stage. I said: ‘Chuck, you want me to introduce you to the band?’ He looked at them. He said: ‘Hello, hello, hello,’ to each one in turn. There was no set list, no nothing. They had no idea what he was going to play.

I went to the microphone and said: ‘It’s a great honour, would you welcome please, the Man, Chuck Berry.’ One, two, one, two three. They went right into it.

Chuck did his thing. He did his chicken dance back and forth across the stage. After forty-five minutes, he came back over to my side of the stage. The kids were going crazy, screaming: ‘More! More! More!’ Chuck put his guitar in his case. I said: ‘Chuck, what’re you doing?’

‘What is it?’ he said. ‘What is it?’

I said: ‘Chuck, listen to that applause.’

‘No,’ he said. ‘I don’t hear it. I don’t hear it. They don’t want me.’

He was doing this jive Scatman Crothers routine on me. ‘YEAH!’ they were all screaming. ‘MORE!’ He couldn’t help but hear it.’ They don’t want me, boss,’ he said. ‘They don’t want me, boss man.’

I knew it was a number. But I figured I had to get into it, or else.

‘Chuck,’ I said. ‘They want you. They want you.’

‘They don’t love me,’ he said. ‘They don’t love me.’

By now, he was strapping on his case to leave.

‘They want you, Chuck,’ I told him. ‘You can’t leave. They love you.’

He leaned over to me. ‘They love me?’ he said. ‘They want me? I’m going out there.’ He opened up the case. ‘I’m comin’,’ he said. ‘I’m here. And I love you.’

He went back to the microphone, and said, ‘Yeah, you love me, you want me, yeah, and one, two, one, two, three.’

What he was really saying to me was ‘They want me, they love me, but you’re not paying me enough money. Why aren’t you paying me more money? Next time, you’re gonna pay me more, right?’

And I was saying: ‘Right.’

None of it showed: Berry’s delivery was unfailingly euphoric, and his playing was so enthusiastic, so urgent – so heroic, really – that you never really noticed how crude it was, how out of tune the guitar had gone, how savage the whole thing sounded. (If you did notice, so much the better: you might have got the idea that you, too, could make as glorious a racket.) Eight years ago, I saw Berry performing on a Los Angeles talk show – he sang ‘Johnny B. Goode’ and duck-walked across the stage like a twenty-something. He was a month shy of his 82nd birthday.

Comments

-

20 March 2017

at

9:25pm

Boursin

says:

A nice tribute, but the Stones' first single was actually "Come On". Their version of "Carol" was released as a single, but much later, and only in Italy and Finland.

-

20 March 2017

at

10:50pm

Alex Abramovich

says:

@

Boursin

Oops, I reversed it, didn't I? Many thanks for the catch, we'll flip it around.

-

21 March 2017

at

4:23am

Bob Beck

says:

The first Chuck Berry performance I ever saw (never saw him live, alas) was probably his appearance in the concert scene in *American Hot Wax*. Not a great movie (I don't think, though maybe I should watch it again), but a good concert sequence (I thought then, at least). At the time (1978) even rockstars in their late thirties got sneered at as over-the-hill; the Stones, in their forties, were routinely written off as past it: though the product they were putting out didn't help their case much.

-

21 March 2017

at

1:17pm

Simon Wood

says:

This crit has brought the litt out in the songs beautifully and reiterated that anyone who made it big played over and over again to get it right - they weren't sloppy, as the squares said.

-

21 March 2017

at

8:53pm

Bob Beck

says:

@

Simon Wood

And not just the squares -- there's a tradition in pop criticism of disdaining polish, or at least hard work and professionalism, in favour of "spontaneity." Though that attitude (too often ill-informed and -thought out) has mostly had its day by now, I'd say.

-

21 March 2017

at

10:16pm

Alex Abramovich

says:

@

Bob Beck

Thanks for these thoughtful comment. Yes, the songs were super-polished. And the sloppy/spontaneity thing: Yes, yes. A lot of that was just straight -up racism: If an African-American artist did something great, it had to be "instinctual." "Primitive." "Authentic." But my informed guess - though I've never seen anyone come and out say this - is that a lot of the backlash had to do with studio musicians bristling at unschooled (as in, couldn't read music) musicians suddenly getting to work in studios. Much of the rock and roll coming out of Atlantic Records in the 1950s: Those were jazz musicians "playing down." Chuck Berry wasn't playing down. He was playing with total commitment and enthusiasm. Although - another yes - he *was* rough, or could be. That, too, was part of the appeal. The music was super-sophisticated on the one hand, raw on the other. Maybe the most interesting answer, here and elsewhere, is "both"?

-

22 March 2017

at

2:05am

Bob Beck

says:

@

Alex Abramovich

Thanks for the original post, which is one of the best tributes I've read; for one thing, I learned more than one new thing about Berry. (New to me, I mean. I winced at his dismissal of Wire and the rest -- bands I like -- and haven't yet been able to bring myself to click on that link).

-

22 March 2017

at

11:36am

Simon Wood

says:

@

Alex Abramovich

I was crossing a busy junction in Camberwell the other day and fell in step with a fellow pedestrian who said he was a little baffled by the traffic. He was Zack Guin, the bass player from the Fatback Band who were playing at Ronnie Scott's the next night and staying in a hotel in Camberwell.

-

22 March 2017

at

5:01pm

Mr A J L Cruickshank

says:

I was touring the US in 1967 on a Greyhound $99 for 99 days ticket with my sister when we passed through San Francisco. Friends as they do in the States had passed us down the line and we were put by a couple of friends of friends. They introduced us to the Fillmore where we heard Mike Bloomfield's American Flag, and Moby Grape among others but also Chuck Berry backed by the Steve Miller Blues Band. In the second set Steve Miller was ill, and Jorma Kaukonen, lead guitarist of Jefferson Airplane, took over. As the Fillmore was then known as much for its light shows and psychedelics as for the bands, it only seemed strange in retrospect that the Berry's rock songs should fit so well into a very different ambience. Alternatively, it says a lot about how much white Chicago blues style had drawn from the same fund of black blues and rock - as the Stones would testify. Afterwards we shook hands with CB as he was putting his guitar into the car boot. Unforgettable.

-

26 March 2017

at

2:27pm

Timothy Rogers

says:

In the late 1950s, as a teenager in Baltimore (the one in Maryland, USA, not the one along the southern coast of Ireland, though there's a historical connection between the two) I had a friend who used to go around singing the lyrics to two Chuck Berry songs that hadn't made as big a splash as several of his better-known hits: "Beautiful Delilah", which had a kind of fast-talking patter rhythm and refrain, and "Too Much Monkey Business." As to the latter, when I sit down to write my monthly checks to pay the usual bills, I often say aloud to myself, "Every day/in the mail/never fail/come another rotten bill - too much monkey business!"

-

28 March 2017

at

7:52pm

csaydah

says:

Or that last verse:

Read moreBerry would have been 51. The friend who accompanied me to the movie, presumably an adherent of this youth cult, made some crack about "atrophying old geezers" playing younger versions of themselves (Jerry Lee Lewis also played in the concert scene). But watching Berry, at least, and even Jerry Lee, I couldn't go along with that. It must have been around that time that I began to wonder if there wasn't something to this old-time rock 'n' roll stuff, after all.

It has been amusing to see fastidious, box-ticking evaluators not quite knowing which box to put Chuck Berry in. He was incredibly cocky, all are agreed - no wonder it's hard to close the lid.

I didn't know that about Atlantic Records but, having recently watched "The Wrecking Crew," it's not that surprising. Some of those players, forty years on in some cases, could still barely conceal their disdain for the music, let alone the ephemeral "stars" they were, in effect, lip-syncing for. But it's hard to begrudge them some sour grapes. The session players got, in many cases, steadier and longer-lasting work than the stars, and got to have family lives besides, but were still virtually anonymous, and never got to hear a crowd roaring for them.

Both-and, as usual, is right. Rock 'n' roll was, in some respects, a business like any other -- if you could fake sincerity, you were a good way toward having it made -- but also unlike most others, jazz maybe excepted: you had to practice spontaneity, or as Lester Bangs said of Iggy Pop, "manage the apocalypse". Maybe the music bossed the culture for as long as it did, in large part, because of how gleefully it embraced -- or, alternatively, ran roughshod over -- so many kinds of contradictions. When it mostly lost that ability, it was time for something else to take its place.

And of course it's silly to personify a form of music like that -- except that Berry, giant though he was, evidently tapped into something bigger yet.

Fatback virtually invented disco from the scraps of music they found on the street in New York City. They are also credited with the first hip-hop record - but their main category would be funk, something I was never interested in because I thought it "loose, sloppy, undisciplined" and (probably) "black".

I listen to it now and admire its taut, sprung rhythms. It is intensely disciplined, minimal music that runs with the beat of the heart and feet and surfs the brainwaves.

Bill Curtis, the founder, is 85, talks of the origins of the music as "street funk". He was classically trained. The band were touring Britain and on their way to Gorleston (Great Yarmouth).

I am in awe.

This is not just nothing. It raises the whole question of the diaspora and the reimportation of its music and culture back into Africa - it ain't just fun.

Workin in the fillin station/Too many tasks/Check the tires/Check the oil/Check the fuel/Dollar gas, aah.

If you hadn't caught the drift by then, that aah made it very, very clear.