Essex, 1951

Gillian Darley

The Festival of Britain showed postwar Britain what it might yet be. The crowds flocked to London to see the Skylon and visit the Dome of Discovery. Peter Laszlo Peri’s concrete Sunbathers writhed on a wall at Waterloo Station (recently found lying in a hotel garden in Blackheath, they are being restored after a crowdfunding campaign and will soon return to the South Bank) as the visitors came off the trains in their thousands. Rowland Emmett’s toy railway was the main attraction at Battersea Pleasure Gardens. More seriously, the Living Architecture exhibition in Poplar, the Lansbury, though still largely under construction, offered a prototype for modern New Town living. The estate caught the local imagination, showing how enlightened planning, social policy and architecture could be harnessed.

There were Festival sites outside London, too: Bristol’s rebuilt Colston Hall (now due for another refurbishment, and renaming); Liverpool’s restored Walker Art Gallery; the village of Farmington in the Cotswolds, with its prizewinning stone bus shelter (now listed); the village of Trowell in Nottinghamshire, which Herbert Morrison had said in Parliament was being included because it was ‘an example of modern social problems in a village’ whose residents were ready to ‘have a go at improving their amenities’. An unidentified MP shouted that Morrison’s scheme sounded more like a funeral than a festival.

‘The Festival Begins at Home,’ Picture Post declared on the cover of its first issue of 1951. Alongside photographs of thatchers, blacksmiths and weavers (some of them art school graduates), Fyfe Robertson enthused that ‘if the South Bank Exhibition is a great shop window, a corner of Essex will be a living stage, where the audience can walk among the players, and the players will be village people going about their daily work, or combining in their normal recreations.’ The three Festival villages in Essex had been chosen with care. Great Bardfield had been an artists’ colony since Eric Ravilious and Edward Bawden fell on it in the early 1930s; Finchingfield, with its archetypal village green, was full of ‘theatrical settlers’ such as Val Gielgud (and Dodie Smith); Thaxted prided itself on its musical life, since Gustav Holst had lived there and the ‘Red’ vicar, Conrad Noel, held concerts in his luminous, lofty medieval wool church.

The fortnight-long Three Villages Festival had been the idea of Essex Rural Community Council. Special permits came from the Food Office for catering, extra police and special constables were drafted in to regulate unprecedented numbers of cars and people. The villages’ Women’s Institutes had made sterling efforts in the organisation of events. The RCC reported on the plethora of activities and concluded it all a great success. But they also had a serious message to convey.

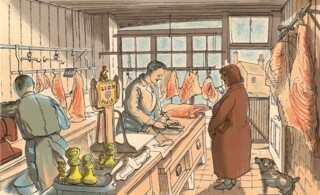

In many ways, Bawden’s Life in an English Village (1949), 16 lithographs of life in Great Bardfield, had already done the job. He showed the pub, the butcher and the baker, but also the ‘child welfare clinic’, the chapel as well as the church. Noel Carrington’s trenchant introduction argued that the village ‘cannot remain for the benefit of the tourist a shell of its vanished social life. The agricultural engineer cannot be housed in the village smithy.’ One of the strengths of village life was to show ‘public spirit in any common effort’, but the ‘touching of caps’ was over and so too was the boredom and the ‘rheumatism from damp floors’. Carrington, like the Festival organisers, was a progressive optimist.