Post-Internet Art

Alice Spawls

The Zabludowicz Collection in Kentish Town is housed in a former Methodist chapel. The building became home to the London Drama School in 1963 – they were the first in Britain to use Stanislavsky’s system – and remained so until 2004. Ten years ago it opened as a gallery, showing works from the collection of the Finnish-British millionaire Poju Zabludowicz (his private investment company owns, among other things, half of downtown Las Vegas; he’s also a major Tory Party donor) and his wife, Anita. A former acting school seems like an appropriate venue for their current exhibition, One & Other, curated by a group of MA students, which is concerned with personas and performance (it closes on Sunday).

Much of the original chapel has been maintained, in a knockabout way, so there’s a stage and wings (side chapels) and a dress circle above with wooden benches (the back of the stalls is now the foyer). Gillian Wearing’s Sleeping Mask, a sort of living death-mask of her own face cast in resin, is illuminated in the centre of the stage, like a discarded prop. It’s a provocation: there’s a mask but where are the actors? There are lots of characters represented in the show – in photographs and videos and 3D animation – so perhaps we’re meant to think they’ve all slipped behind screens, but it makes you look at your fellow gallery goers too.

Wearing is best-known for her ironic self-portraits in which she dressed up as members of her family, as her younger self and as other people; often re-creating everyday snapshots with eerie fidelity. They’re not as staged, or grotesque, as Cindy Sherman’s ‘self-portraits’, though they’re often unsettling – maybe all isn’t as it seems. The Swiss artist Ugo Rondinone performs a similar trick in I don’t live here anymore, a series of prints which show his head pasted onto (female) fashion shoots. They’re a bit uncanny – he has a moustache – but almost seamless, and perhaps not as surprising as they were six years ago, given the rate at which fashion steals from its satirists. Isa Genzken’s mannequin (one from a group of forty) is much harder to read: dressed in a random assortment of clothes and props, like a charity shop bad dream, it rejects all sartorial logic. Strange gold headdress, white shirt, multicoloured cape, glitter trousers …

These works – exhibited on the upper gallery – try to say something about self-presentation more widely; most of the artists in the downstairs space draw our attention to the way we present ourselves (our multiple selves) on the internet. Amalia Ulman was called ‘the first artist of Instagram’ a few years ago, when she revealed the hoax behind her 18-month online project, Excellences and Perfections (again, everything is plural). The idea was to perform a series of Cindy Sherman-like transformations on the internet and see how far she could push her audience. She cast herself first as a wannabe It-girl in LA and posed, pouting and posturing in bathroom mirrors, for Instagram shots. She posted pictures of hotel rooms and breakfasts. She got more and more followers, and she began to involve them in the story – writing confessional messages and describing her decision to have breast surgery in detail, with graphic (fake) images. Her thousands of followers applauded. She performed the celebrity arc: a downward spiral into drugs and black hair dye, before a breakdown, disappearance and triumphal return as a ‘balanced’ new woman, posting generic pictures of yoga and green juices. Then she confessed that it had all been a trick.

If there’s an artwork as such in this, it must be her Instagram feed: in the exhibition you watch a short video describing the project. When the Tate included Ulman in Performing for the Camera last year, they claimed that the gallery was the natural – and intended – endpoint for the ‘work’. It’s not so easy to agree. But neither was Ulman’s performance – seen by people who didn’t get it, and then didn’t like it – a piece of art until the hoax was revealed. The work itself is as diffuse and unlocated as the medium. It would have been better had some of the images she created been printed and exhibited in their own right: looking at them online they seem all too fake – an artist’s version of this world which gives itself away – but maybe that’s because we now read them in retrospect.

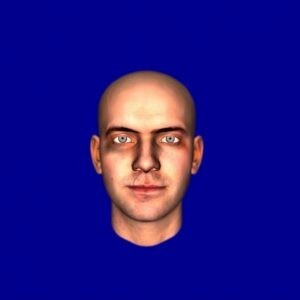

Many of the artists represented here are working with digital forms – what’s sometimes called New Media or Post-Internet Art (Internet Art proper is already shelved and classified: it refers to the first, comparatively naive artistic responses to the internet in the 1990s and early 2000s). Post-Internet artists are the first generation to have grown up with mass digital technology, and often with parallel selves on social media (they wouldn’t call it ‘virtual’). They don’t just respond to the internet but often try to use it as a medium. Ulman’s project is the most straightforward in this respect: it has a narrative, and it mimics forms we recognise. Others work in less conventional ways. Ed Atkins’s piece No one is more WORK than me features a CGI avatar called Dave: a pixelated head (mapped on his own) against a blue screen. All the other video pieces in the exhibition require headphones, so Dave gets to hold court on an eight-hour loop. It’s part aggressive monologue, part whimsy. Snatches echo round the nave: ‘I don’t wanna get it, This is what I am, It’s just a bit of blood, Do me a favour, can you do that, Read my lips, read my lips, read my lips’ (and we can just about read his lips). It’s not very nice listening to him: is he an internet troll given a face? Or just any old bully?

There’s something a little off though – every so often he breaks into song (Purcell?). And the video is a bit cranky: it jumps and crinkles. Although it’s a decent animation, it’s far from the quality of the movie studios, and looks old-fashioned, almost vintage. Technology itself is a character, or has characters, it seems. (Some Post-Internet artists seem nostalgic for the aesthetics of the early internet and primitive softwares.) Cécile Evans’s video The Brightness also has a strange texture. It shows two avatars – one is Evans playing herself, the other Evans as a nurse ‘specialising in phantom limbs’ – whose conversation is suddenly interrupted by an animation of little dancing teeth; they perform a routine in rows. It feels slightly absurd to be watching it in a gallery, with headphones and 3D glasses, but I suppose that’s the point: it brings to mind the weird-familiar feeling of airports and Premier Inns, foreign TV and mistranslated product packaging. Evans trained as an actress but has said she found it too limiting. (Are there limits on absurdity in digital art? Evans’s installation Sprung a Leak at Tate Liverpool features three robots, 27 video screens, digitised pole dancers and a fountain. She decided against giving the fountain a speaking part because it would be ‘too ridiculous’.)

One of the surprising things about these artists, which isn’t always apparent in the work, is how despondent, even dystopian, they are about the internet. They might fetishise PDFs and encourage open platforms and shared interfaces (Wikipedia as art), but when interviewed they describe the web as pernicious, and technology as the glossy face of human misery. It makes sense then that their work should try to defamiliarise its forms, like a digital Dada. There’s a divide, though, in their audience, between a younger generation, steeped in memes and chats and the valences of photo filters, and those who find the first premise alienating, let alone the subversion. It might be useful to see this show with a 16-year-old. Then again, a 16-year-old might not be very impressed: their use of Instagram is coded by much more sophisticated (if unexamined) social rules than Ulman, say, is interested in – and the irony of her posing for fashion photoshoots following her success won’t escape them either.

Two more optimistic works stand out in the general gloom. Jon Rafman’s New Age Demanded is a series of futuristic busts made on a 3D printer, and it’s hard to resist touching their strange plastic-looking surfaces. They are realisations of digital sculptures, though ‘realisation’ isn’t quite the right word (the ‘real’ thing is in the computer software), and they seem to translate the fluidity of their virtual medium into the physical world. Leo Gabin, in the opposite direction, points to the hidden beauty of the internet in his short video Stackin, which shows clips of amateur rappers performing finger-tutting (a sort of intricate hand dancing which can incorporate gang signs). The clips are laid over Bach’s Prelude to the First Cello Suite; they fit the music beautifully – an especially nice move is one where the folded hands open out and beat like a bird – and the articulation of their fingers is as hypnotic as any cellist’s digital kinetics.

Comments