Bells after Fifteen Rounds

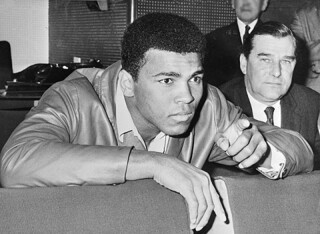

Michael Carlson · Muhammad Ali

1. When We Were Kings is the fitting title of Leon Gast’s superb documentary about the Rumble in the Jungle, Muhammad Ali's battle with George Foreman in Zaire, where he regained the heavyweight crown. It was a time of giants in boxing’s most glamorous division. Foreman said that he, Joe Frazier and Ali were like one person; they had been forged together in the public imagination, but there were also Sonny Liston, Floyd Patterson, Ken Norton, Henry Cooper, Ernie Terrell: men over whom Ali needed to triumph to establish himself, and who now shine in his reflection. Watch the moment Foreman falls in the film: at ringside George Plimpton is frozen in drop-jaw disbelief; Norman Mailer is already beginning to celebrate.

2. Muhammad Ali would have been the most important sportsman of the 20th century even had he not become a symbol for battles of conscience, for racial justice, for people far removed from power, for religious belief, for so much else. He was the most recognisable human being in the world; he could go nowhere without being mobbed. But it started on a smaller scale. When he burst on the scene after winning his Olympic light-heavyweight gold in Rome, he brought something new to sport: showmanship and self-promotion. He carried the trash-talk of the playground and the braggadocio of the wrestling ring into the arenas of 'legitimate' sport. TV was beginning to turn sportsmen into entertainers, like movie stars. This did not mean Ali was embraced immediately or automatically. To many 'traditional' sports fans, mainly whites, he was a loudmouth, he was uppity, he needed to be put in his place.

3. From 'I Am the Greatest', a poem by Cassius Clay: 'The fistic world was dull and weary/with a champ like Liston things had to be dreary.' I once wrote of Sonny Liston that ‘his only skill was hurting people.’ The white audience had a problem trying to decide if they should root for Liston, a thug who'd learned his boxing in prison, to shut 'the Louisville Lip' up. Not that they doubted he would; he was a 7-1 favourite. Clay spent the build-up to the fight in February 1964 entertaining celebrities like the Beatles (his win over Henry Cooper a few months earlier had made him a star in Britain) who flocked to Miami; he called Liston a 'big ugly bear' and seemed so hyper at the weigh-in that sportswriters claimed he was scared to death. Clay's victory shocked the world. Soon afterwards, he announced his conversion to Islam and changed his name to Muhammad Ali. A lot of people still believe Liston took a dive in the rematch in Lewiston, Maine, falling in the first round to Ali’s ‘phantom punch’, a blow thrown so fast that spectators missed it.

4. Floyd Patterson may have been the first black ‘white hope’, the ‘credit to his race’ the boxing establishment hoped would ‘win the title back for America’. He had been destroyed twice in short order by Liston. He insisted on calling Ali by his 'slave name', Cassius Clay; Ali responded by calling Patterson ‘the Rabbit’. The generation gap was already apparent in our house in late 1965: my father was supporting Patterson. Ali then beat four white fighters in a row in the space of six months. By the time he'd finished, my dad was an Ali fan.

5. Ernie Terrell, too, in the build-up to their match, insisted on calling Ali by his 'slave name'. Ali called Terrell 'an Uncle Tom nigger' and said 'I'll make him eat those words, letter by letter.' The fight was held in February 1967 in the Houston Astrodome, with 37,000 spectators, the biggest indoor boxing crowd ever. For 15 rounds Ali taunted Terrell – ‘What’s my name?’ – as he inflicted as much damage as he could. Terrell nearly lost the sight in his left eye. 'We were fighting,’ Terrell said in 2009. ‘I bore no animosity. What he say, all that, don't count. That was his way of promoting the fight.’

6. ‘I was the onliest boxer in history people asked questions like a senator.’ When Ali was called up for the draft in 1966, he had to be reclassified 1A, because he'd originally been judged 1Y, fit to be called up only in times of 'national emergency' because his IQ was measured at 78. 'I said I was the greatest, not the smartest,' he said at the time. He would belie that statement many times.

7. 'No Viet Cong ever called me nigger,’ Ali said. He refused induction in April 1967. His New York State boxing licence was withdrawn and he was stripped of his titles. In June, a jury took only 20 minutes to convict him, and the case went to appeal and eventually to the Supreme Court. ‘What should I shoot them for?’ he asked. ‘They never called me nigger. They never lynched me, they didn't put no dog on me. They didn't rob me of my nationality, rape and kill my mother and father … How can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail.’

8. The cover story of the April 1968 issue of Esquire was 'The Passion of Muhammad Ali'. The picture, created by George Lois and shot by Carl Fischer, is a homage to Mantegna's Martyrdom of St Sebastian, Ali in his white boxing trunks penetrated by arrows. The issue hit the stands as President Lyndon Johnson announced that he 'would not seek, nor shall I accept' the nomination of his party for president. It was easy to think that we had won. Easy, but delusional.

9. While banned from boxing, Ali toured college campuses giving lectures. Sometime – I think in the spring of 1970 – I was in a packed ice hockey rink at Wesleyan, listening to Ali, and hanging around afterwards to applaud as he left by car. There is a clip from around that time on YouTube of Ali facing down a young critic, telling him that white people are the enemy, not the Viet Cong. 'If I die, I'm gonna die right here fighting you,' he said. We believed him, and we somehow believed that 'white people' didn't include us. It made my own decision to pursue conscientious objector status, and face the consequences, somehow easier.

10. From 'I Am the Greatest' by Cassius Clay: 'This kid fights great, he's got speed and endurance/If you sign to fight him, increase your insurance.' Ali’s enforced absence from the ring cost him some of his speed: few opponents had been able to hurt him with solid punches before. I saw or listened to the three fights against Frazier, the Rumble in the Jungle against Foreman and the two split decisions against Ken Norton, and I've since watched them over and over again, Frazier ploughing forward, head down, left arm low and cocked to deliver the hook that caused so much damage. Watching the ‘rope a dope’ strategy against Foreman, I think about the courage, the intelligence, the risk Ali took. And mostly I think about the long-term damage those big fights inflicted on him.

11. In 1976 I was a press liaison at the Montreal Forum during the boxing finals. Leon Spinks's win over Sixto Soria was the greatest amateur bout I've ever seen. In 1978 I watched Ali retake his title from Spinks, on closed circuit at the Dominion in Tottenham Court Road. It was the result I wanted, but I took no joy from it. Ali was nearly 40 when the fifth and final loss of his career, a difficult-to-watch unanimous decision against Trevor Berbick, at last convinced him to retire.

12. From 'I Am The Greatest' by Cassius Clay: 'Then someone with colour, someone with dash/brought the fight fans running with cash.' Clay understood from the first what he was doing. In his poem he refers to himself as a new kind of fighter, to boxing's 'New Frontier'. He claimed to have based his style on the wrestling star Gorgeous George, but it's more likely he was copying 'Classy' Freddie Blassie, the self-proclaimed 'King of Men', who was big in Louisville when Clay was young. In 1976, Ali fought the Japanese wrestler Antonio Inoki, and brought Blassie in as his manager. Ali said it was going to be a real fight, but that was never Inoki's idea. Negotiations over how the fight should be scripted broke down; neither man would do a job for the other. So we saw Inoki lying on his back in the fight, using his feet to keep Ali away – easily the least edifying moment of Ali's career. He was born to be a boxer and a performer, not just a performer.

13. In 1988 I was in Pesaro, Italy, broadcasting a middleweight title fight between Sumbu Kalambay and Mike McCallum. The night before the fight I stayed up late with Angelo Dundee, Ali's trainer. I don't think I've ever heard anyone describe someone the way Angelo did, somewhere between respect and worship, and it was sincere. I learned a lot about boxing on that trip, but I never discovered whether Angelo actually sliced Clay's gloves to buy time in the first fight against Cooper.

14. At the Atlanta Olympics in 1996 I was in charge of host broadcast coverage of basketball at the Georgia Dome. The bane of my life was any game with the US Dream Team II, because of all the journalists desperate for press seats not so they could work, but just to see the superstars. But before the game with Angola, Ali, who had lit the Olympic torch to open the games, arrived courtside. The Angolans broke off their warm-ups to crowd around, followed by the Dream Teamers who rushed out of their locker room to join them. Here were the world's biggest superstars turned into fan boys just like the rest of us. I walked casually down to the court, fan boy myself, to admire the admiration.

15. On Saturday I woke to the news that Ali was gone. I rummaged through some boxes and found my copy of Cassius Clay's 45, 'I Am The Greatest', b/w 'Will The Real Sonny Liston Please Fall Down'. It's more than half a century since I first heard it. Mine’s a DJ copy I won in a college competition; on the record as released the flip side is Ali singing 'Stand By Me'. I don't have a record player any more, so I couldn't listen to it. I just looked at the pictures on the worn sleeve and heard the voice in my head, clear as when I was 12:

This is the legend of Cassius Clay, the most beautiful fighter in the world today … If Cassius says a mouse can beat a horse, don't ask how, put your money where your mouse is … if Cassius says a cow can lay an egg, don't ask how, grease that skillet.

The world that brought that character into the spotlight no longer exists, and a great part of the reason for that is Muhammad Ali.

Read more in the London Review of Books

John Upton: Ready to Rumble · 16 March 2000

Thomas Powers: Malcolm X · 25 August 2011

Jeremy Harding: Mike Tyson in Atlantic City · 31 August 1989

Comments

-

6 June 2016

at

11:15pm

Simon Wood

says:

We got a television set just in time for the 1960 Rome Olympics when I was 6 and my sister 3. We sat under it and watched everything that came on.

-

14 June 2016

at

5:39pm

gary morgan

says:

@

Simon Wood

I was lucky enough to be 11 hen Ali fought Frazier and had read with trepoidation about what this Frazier fellow had done to Ali's stablemate Jimmy Ellis. When Ali lost to Ali he had lost the speed of pre-ban days but the left hook he got up from in the 14th, steady legged, was amazing.]

-

14 June 2016

at

5:40pm

gary morgan

says:

@

gary morgan

Sorry, I meant to type "when Ali lost to Frazier." Doh!

-

14 June 2016

at

6:46pm

Blackorpheus7

says:

Sonny Liston was not a "thug"; he was caught up in circumstances which he could not control.

-

14 June 2016

at

8:59pm

gary morgan

says:

@

Blackorpheus7

A fair point made in Nick Tosches' tendentious if excellent biography of a sad life, 'Night Train.' Liston's Vegas tombstone tersely gives just his name and the simple words 'A Man.' Glad someone remembered him.

-

15 June 2016

at

3:09pm

Leon Ashford

says:

What a superb essay. Unique in structure, compelling in content. It is an immense credit to the LRB that it publishes work of this calibre.

Read moreWe then followed Ali's every move on "Grandstand". He's quite a character, said Harry Carpenter, always something to say, "They call him the Louisville Lip."

The whole world can claim Ali, but as far as I'm concerned, he belongs to me and my sister.

The there was Foreman, so scary in the early '70s that everyone avoided him and journalists' fear of his brooding, intimidating presence. I mean, rope-a-dope George!

Amazing man, wonderful mover and a boxer the like of which the Heavyweights hadn't seen nor will again. No saint, true; the Elijah Muhammad days were wretched but he came to regret the estrangement from Malcolm and to work to unite not divide.

To see Norton (Ali's true nemesis, he was robbed at least once), Frazier, Foreman.... well what an era.

Can you imagine, say Mayweathe, that desiccated calculating machine, doing anything for his principles? Nope. Ali did and was brave, funny - I mean really funny, "I'm a bad man" said on beating Liston was hilarious - and a one-off into the bargain. Lucky us to share an era with him.

R.I.P. Muhammad Ali.

Gary Morgan

The only blot on Ali's copybook, and it was a huge one, was his siding with Elijah Mohammed in the Nation of Islam's ostracism of Malcolm X. He should have stuck with his friend, for Malcolm was a man of unimpeachable character and decency.