Brodsky among Us

Anna Aslanyan

Joseph Brodsky would have turned 75 on Sunday. In March, the Moscow publisher Corpus released Бродский среди нас (‘Brodsky among Us’), a memoir by Ellendea Proffer Teasley, who met the poet in 1969 in Leningrad and remained friends with him until his death in 1996. She was a graduate student at Indiana University when she went to the Soviet Union with her husband, Carl Proffer, who taught Russian at Michigan. In 1971 they set up the Ardis press in Ann Arbor, to publish the work of writers banned in the USSR, including Mandelstam, Tsvetaeva, Bely, Nabokov, Sokolov and Aksenov.

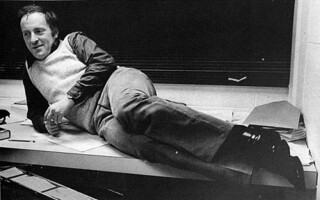

On first meeting him, Proffer Teasley thought Brodsky looked like an ‘American graduate’. In fact he had left school at 15 and worked in odd jobs. ‘A school is a factory is a poem is a prison is academia is boredom,’ he later wrote. In 1963 he was charged with social parasitism, imprisoned, and the following year sentenced to five years’ exile. He was released after 18 months of working as a farm hand in a northern village. The Proffers were struck by his ‘determination to live as if he were free’ in a totalitarian society. They soon became close, though there was plenty they disagreed about: Brodksy supported the Vietnam War, for instance, on the grounds that every means available should be used to stop the spread of Communism. For all his intelligence and charm, Proffer Teasley writes, Brodsky tried to ‘make the world fit his own idea of what it should be’ and ‘could only ever be consistent within a poem’.

In 1972 the Soviet authorities told Brodsky he had to leave the country. He agreed, knowing he’d never be able to come back; even after the collapse of the USSR he chose not to return. The deal offered by the KGB was to emigrate to Israel, but Brodsky's sights were set on the ‘anti-Soviet Union’. Proffer persuaded the University of Michigan to give Brodsky a job, and he came to Ann Arbor. It was there that he wrote ‘The Hawk's Autumn Cry’:

He senses a mixture of trepidation

and pride. Heeling over a tip

of wing, he plummets down. But the resilient air

bounces him back, winging up to glory,

to the colourless icy plane.

Brodsky's predecessors at his teaching post were Frost and Auden, two major influences on his poetry. His students liked him, though they complained about his accent: his English improved fast, but he never lost his Russian intonation. Ardis published Brodsky in both Russian and English, and there was constant fighting over translations: he wanted to keep the rhyme and metre at all costs. Later, when he started translating his own poetry as well as writing in English, Proffer Teasley often had to explain to people what a great poet Brodsky was in his own language.

In 1968, on finishing a Beckett-inspired poem based on his experience of punitive psychiatry, Brodsky told his friends that one day he'd be awarded the Nobel Prize. He won it in 1987. Proffer Teasley's memoir, translated by Viktor Golyshev, who also knew Brodsky, is already in its third impression; last month she gave several sell-out talks in Moscow and St Petersburg. Visiting Russia in 2003, Proffer Teasley was taken aback by a ‘new party line’ aimed at portraying Brodsky as a national hero and a martyr. The attempts to canonise him continue, sometimes taking grotesque turns: a few days ago the papers reported that ‘in the run-up to Brodsky's anniversary’ the staff of the St Petersburg prison where he spent over a year ‘discovered the cell in which he was kept’. I hope the story is read by anyone still wondering about Brodsky's decision never to return to Russia.