‘L’Arabe du futur’

Ursula Lindsey

Riad Sattouf’s father travelled from a small Syrian village to Paris in the 1970s. He met Sattouf’s French mother at university there. After they graduated and their son was born, the family wentfirst to Libya under Gaddafi and then to Syria under Assad. L’Arabe du futur, Sattouf’sautobiographical graphic novel, tells of his strange childhood spent in the shadow of Arab dictators and his father’s delusions. Two more volumes are forthcoming, and an English translation isunder way.

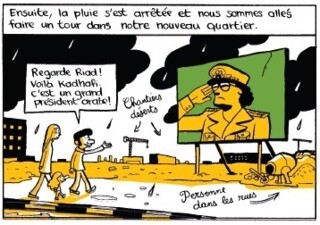

In Libya, where his father accepts a teaching post, the family lose their university housing immediately to squatters who invoke Gaddafi's ban on private property. Sattouf’s mother, Clementine,nearly gets into trouble after she breaks into hysterical laughter reading out propaganda on the radio. Sattouf remembers the crowds jostling to buy unripe bananas and Tang, the afternoons spentplaying unsupervised with the children of other foreign professors. In a child’s worldview, the strictures of a dictatorial regime are no more bizarre than most other rules.

When Sattouf’s father decides to take his family back to Syria, things turn almost farcically awful. He didn’t do his military service, so has to bribe his way past army officers at the airport.The family waits as a group of cab drivers has a brawl over who will take them. Back in the village, at the family home, the women sit in a separate room and eat the men’s leftovers. Sattouf’sfather discovers that his brother has sold his land. The village is full of rubbish and feral little boys who wave sticks and threaten Riad.

Most of the small boys in the book play violently; they fight each other, imitate the dictators they see on TV, and threaten their mothers with weapons they find in the house. When their fathers –who beat them – come home, they sit in silence against the wall. The book indicts the brutality of an education that recognises no other source of authority than the monopoly on violence. Itsuggests that a cult of strength flows from a shameful sense of weakness, whether that of a terrified child or a colonised and defeated nation.

When Sattouf went to live in rural Syria, the country had recently fought two wars with Israel. His father’s village was 40 kilometres from Hama, which in 1982 was the site of an uprising againstAssad, and a subsequent massacre by government forces.

But the cartoonist’s focus is on his dysfunctional, not to say menacing family. His cousins are little creeps who insist he’s a Jew – an enemy – because he's blonde. The boys’ free-floatingaggression and mob mentality culminates in the lynching of a puppy.

Sattouf seems to have been a precocious child, with an eye for the foul and the grotesque: we get rubbish-strewn streets, public defecation, his baby brother eating a cockroach, a farting passengeron an aeroplane. Of course little boys are fascinated by this sort of stuff, but the parade of nastiness soon gets tiring and you start to wonder if these are Sattouf’s only childhood memories, orif he is selecting them to undermine his father’s youthful and grandiose aspirations (his belief in the ‘Arab of the future’ of the ironic title). With his relentless attention to bestialbehaviour, Sattouf comes uncomfortably close to implying that Arabs are animals. He seems to have become alienated from one side of his family very early: he compares his father to a monkey andspeaking Arabic to retching.

There is a mystery at the heart of the story that I hope future volumes will tackle: the parents’ marriage. Sattouf portrays his father as a loser – sweet but feckless, ignorant, an overgrownchild. His mother on the other hand is shown as uniformly kind and reasonable. Yet all she ever does is gently disapprove and remonstrate. She irons her husband’s clothes while he lounges aroundreading the Green Book. After the puppy lynching, she decides Riad isn’t ready for the local school, and they travel back to France. But the book ends with the whole family headed back to Syria.Readers have caught glimpses of the brutal school he’ll be going to and can expect the worst for him there. But we also know he will survive, become a successful Paris-based cartoonist, and producethis memorable règlement de comptes.

He’s had a strip in Charlie Hebdo since 2004 but wasn't in the office on 7 January. His contribution to the next issue was drawn from life, a young man of Arab origin on the phone in thestreet on the day after the massacre, overheard arguing with someone: 'Listen bro, they're some guys, they drew stuff, that's it. You don't kill them for that, that's it.'