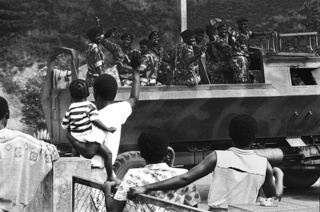

‘On the Frontline’

Simon Bright

For the last three months I’ve been in Johannesburg helping to curate an exhibition of photographs at the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory, part of the Mandela Foundation. On the Frontline looks back over the difficult years, from 1975 to the early 1990s, when South Africa’s neighbours gave their support to the liberation movements in South Africa – both the ANC and the Pan-Africanist Congress – and the South-West Africa People’s Organisation, in return for harsh treatment by the apartheid regime. Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia and other leaders acted on the conviction that their newly won freedom was illusory until apartheid was a thing of the past.

I knew the photographers whose work features in this show – a few are no longer alive – quite well: I’m Zimbabwean; I spent most of that period making films in the countries that were attacked or invaded by Pretoria. Seeing these pictures displayed and captioned in a formal exhibition space for the first time is a powerful reminder of the apartheid era: the raids on ANC houses in Lesotho; the full-scale disruption and violence in Mozambique by Renamo, South Africa’s compliant rebel movement; the invasion of Angola by the South African Defence Force and the support it provided to Jonas Savimbi; the severity of South African repression in occupied Namibia.

I’m impressed at the same time by the way the frontline states fought back. In Angola, tens of thousands died in battle and the civilian population was reduced to hunger and poverty, but the critical phase of the war ended in 1988 with three South African tanks captured or destroyed at the battle of Cuito Cuanavale. The South Africans retreated across the Namibian border to avoid being cut off in southern Angola by a determined Cuban force: the withdrawal began the countdown to Namibian independence and Mandela’s release.

When I got to South Africa earlier this year there was no sign of the violent anti-migrant feeling that was about to erupt. The news was all about the assault on symbols of white supremacy, including the desecration of a statue of Cecil Rhodes and the ‘necklacing’ of the Uitenhage memorial. Then in April there was a wave of attacks on migrants in Durban. The Zulu potentate Chief Goodwill Zwelithini had stirred things up with a speech in March describing black foreign migrants in South Africa as ticks that needed to be plucked off and left to wither in the sun. Zwelithini has backtracked since, but the violence spread to Johannesburg and before it calmed down at least 1800 migrants went back to Malawi and Zimbabwe while others pitched up in ‘safety camps’ in KwaZulu.

Some of the victims of xenophobia, Mozambicans especially, are from the countries that actively opposed apartheid, and though order has been restored, the Mandela Centre for Memory is anxious about more outbreaks. South African liberation was fought for and won at considerable cost to neighbouring countries and their people. At the opening of the exhibition, Graça Machel, the former first lady of Mozambique and widow of Nelson Mandela, spoke about the indifference of the leaders of Southern Africa both to the poor migrants entering South Africa and the poor South Africans who turned on them: ‘Our leadership has betrayed the dream. All of them. They don’t have the big dream to motivate all of us to look up to something bigger than anyone of us.’ Her view is in marked contrast to the assertions from President Zuma’s office that much of the violence against migrants was simply criminal in intent.

The word ‘memory’ in the Mandela Centre’s title isn’t a pious platitude: the idea is to invoke the past to shape attitudes in post-apartheid South Africa and, when necessary, take them on. Anti-immigrant sentiment is something the centre wants to confront, and this show – which runs until mid-July – is part of that.