Separation by Symmetry

Gillian Darley

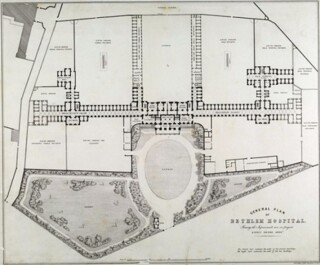

Plans of the 1815 New Bethlem Hospital in Southwark included in the Richard Dadd exhibition at the Watts Gallery, Compton, show complete segregation between male and female inmates. The ground plan consisted of two identical halves, except for the outlying women’s criminal building, which was considerably smaller than the men’s. There could be no chance meetings between men and women in a secure home for the ‘criminally insane’.

When segregation of the sexes is voluntary, the design has to be handled more deftly. The Shakers, Mother Ann Lee’s followers from north-west England, crossed the Atlantic in the late 18th century to establish celibate, self-supporting settlements. The result, as expressed in architectural form, is almost unsettling. The perfect symmetry of an interior, in which one side meticulously mirrors the other, door for door, stair for stair, each fitting answering another, is an absolutist aesthetic that came into its own with functional modernism.

The control implicit in the design goes further. Men and women worked in different trades, so rarely encountered one another in the workplace. But when it came to communal events and meetings, another set of rules, dealing with personal space and distance, were applied. Strict discipline applied even to their posture, whether they were awake or asleep.

The Shakers perfected what they called a ‘living building’: a settlement that served their purposes while also reinforcing their separation from non-believing outsiders. There is only one active Shaker community left, Sabbathday Lake in central Maine, with fewer than half a dozen members. It is the forms of the architecture, and the design of their artefacts, that have endured to tell the tale. The Shakers cared nothing for burial and did not mark their graves. The living building was their epitaph.

Comments