Invisible Women

Lynne Segal

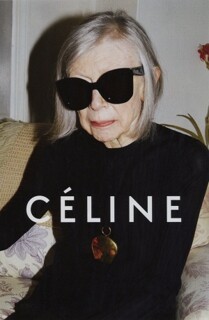

I heard that the octogenarian Joan Didion was to be the ‘new face’ of the Parisian luxury brand Céline when I was in the middle of commenting on a new monograph by Margaret Gullette called How Not to Shoot Old People. It documents countless grim instances of neglect and contempt for the elderly across a vast ageist spectrum. We oldies live in schizoid times.

Old fashionistas are suddenly all the rage (if hardly plentiful) at Vogue and Dolce & Gabbana. Living longer, old people can be encouraged to consume more, especially by cosmetic and fashion industries promising to keep us looking streamlined and elegant. We may, undesirably, be no longer young, but we can at least dutifully defer to the dictates of fashion. Didion even has the skinny look of a fashion model: hardly an inch of flesh, mere bones on which to hang clothes and accessories.

Meanwhile, social media trolls pour forth hate speech against the elderly. Only occasionally is it directed at those with the resources to resist, such as Mary Beard. Older women in need of care regularly report being treated with impatience or disdain, but only the most scandalous cases of neglect attract public notice. There were mild complaints five years ago when Martin Amis, in the Sunday Times, called for euthanasia booths to deal with the threatening ‘silver tsunami’ of old people who would soon be ‘stinking out’ the streets of London. He said he could ‘imagine a sort of civil war between the old and the young in 10 or 15 years’ time’. His words resonate with the constant hum of alarm – almost panic – about the increasing numbers of elderly people, with our distinctive needs.

The most terrifying images of old age – the witch, hag, harridan – have always had a female face, whether in myth, folktale or horror movie. This can have stark material consequences. Women are twice as likely as men to end up living alone in old age, with no companion to care for them. Their pensions are generally smaller, too, as they are confined to fewer areas of the labour market, paid less, and more likely to have taken time out from their jobs to look after other people. In September 2013, the Labour Party’s Commission on Older Women provided stark evidence of the continuing invisibility of older women in public life. Eighty-two per cent of BBC presenters over the age of 50 are men. More generally, unemployment among women aged between 50 and 64 had increased by 41 per cent cent in the previous two and a half years, compared with 1 per cent overall.

In this dismal landscape, it is pleasing that ‘Fabulous Fashionistas’, older women with a flair for bright, distinctive dressing, were sought out and celebrated on TV last year. They were presented as role models for invisible women everywhere. The programme’s producer, Sue Bourne, confessed it had taken her two years to find the half dozen confidently colourful and stylish older women in the UK, but she’s hoping they are setting a trend. Perhaps Didion will boost that trend: her chic self-presentation mirrors her precise, elegant prose. Didion will never frighten the children, unlike the ‘old woman of skin and bones’ in the playground song, who goes ‘to the closet to get her broom’, and may fatten them up for supper. Didion represents instead the cheery resilience that the government and media look for in those older women who are allowed a certain visibility to tell us all how to grow old gracefully. We must all keep looking healthy and feisty; making few demands on others, and least of all on the public purse.

Didion offers the ironic detachment of a woman able to see through the duplicities and deceptions that any celebration of ageing cloaks, knowing that our culture continues to worship youth, and youth alone. Let’s rejoice that she can ride these contradictions, at least for now. As one young fashion model said, ‘It’s so cool, it hurts.’ Quite.

Comments

-

14 January 2015

at

3:28pm

suekatz

says:

Lynne Segal is so right. This whole "elder chic" flurry is annoying on many levels. Not only is the idea of spending your final decades desperately seeking to be fashion-forward sexist, it could only be a goal of the very privileged. The rest of us are more interested in finding a way to stay warm, fed, loved, and respected, than in sucking up to the style machine. Besides, we still need our practical clothes for our continuing role on the barricades. Thanks for this terrific commentary and let's have more from Lynne Segal please.

-

15 January 2015

at

4:36pm

Mila Caley

says:

Lynne Segal encapsulates the contradictions well, as ever touching on a wide range of ideas and analyses in her lively commentary. On the one hand, as an an older woman who has always been impressed by Joan Didion, I felt good seeing this powerful image of her. Ditto Joni Mitchell's picture for YSL. On the other hand, unlike Lynne Segal who ends her discussion by rejoicing that Joan Didion is doing this in a knowing cool way, I feel some disappointment that Joan and Joni, who have contributed so much to women having an intellectual, critical and lyrical voice throughout my adult lifetime have chosen to sell luxury clothes now. Really? But then maybe they need the money.....

-

15 January 2015

at

9:27pm

Simon Wood

says:

An interesting choice of brand for Joan Didion. She could be advertising the lugubrious Louis-Ferdinand Celine, the dark, disgraced, disgraceful writer who is sometimes rated as second only to Proust. Only in France.

-

16 January 2015

at

12:31am

Meredith Watts

says:

It reminds me of Lillian Hellman modeling furs for magazine advertising a few decades ago. They certainly did not choose her for her face -- she had the wrinkles that most life-long smokers have.

-

17 January 2015

at

2:56pm

Margaret M. Gullette

says:

As the North American age critic whom Lynne Segal kindly mentions in her opening, I want to congratulate her on using the occasion of Joan Didion's crowning as a fashion icon to convey Segal's own view of the contradictions of British age culture. Being a good age critic, like climbing a tall pine to get a wide view of the muddled terrain below, is even harder than it looks.

-

17 January 2015

at

10:36pm

Timothy Rogers

says:

Coudln't agree more with Ms. Katz's remarks (and this from a man who just passed 70). Nothing seems more ridiculous than an old person chasing after youthful fashions, or anything "young", for that matter. As evidence in this dock of indictment, I merely point out the ludicrous behavior and appearance of aging rock-and-roll icons -- if anyone lacks self-awareness of how silly they seem, it's these guys and their age-mate fans. Youth is for the young, so let them have it and enjoy it for the moment, which will move on rapidly anyway. The situation is asymmetrical, young folks having no perspective on aging, while old folks have more than enough. Aging with dignity should be the goal -- not in any formal, conservative sense, merely in the sense of knowing what's appropriate and what's foolish.

-

25 March 2015

at

11:12am

Ros Jennings

says:

My response to Joan Didion and Joni Mitchell fronting campaigns for Celine and Saint-Laurent is the same as it is when considering many issues; conflicted. As the research conducted in the Research Centre for Women, Ageing and Media (WAM) where I work suggests, on the one hand the additional visibility of older women in the media is to be applauded but on the other hand the types of older women who are celebrated in the media (and in this case fashion media) mostly conform to an acceptable type (as Joan Didion and Joni Mitchell do). This type is the 'successful ager', the older woman who will not ultimately be a strain on the country's health and social care services (they are wealthy and relatively fit and well). Fashion is an industry that demands consumers and, in turn, neo-liberal economics demands that markets diversify, extend and lock in further consumption. Fashion now targets the 70 + older women who is a 'successful ager' and perpetrates the necessity to maintain what academic Beverley Skeggs discusses as the 'hard work of femininity' along the life course. As an industry, fashion has little reason to actually address all women in their diversity whilst sexism (the everyday kind and the entrenched ideological) perpetuates patriarchal ideals of heterosexual femininity that values what a woman looks like above who they are (and their talents and contributions). In the case of Didion and Mitchell, I will choose to think of them in relation to their prodigious talents (Mitchell in particular is perhaps the musician I admire above all others) rather than the way they look.

Read moreThomas Keneally, surely beyond reproach, regrets that he always liked older women but is now old himself. Joan was always a looker. Maybe she is preserved, like so many old women, by smoking.

No-one deserves to be nice-looking and the whole subject is wretched, in fact it is hardly a serious subject at all outside the wonderful cartoon world of “Vogue”.

Identity politics is creeping up on us like dry rot, but Joan Didion, Joni Mitchell and Vivienne Westwood can do no wrong, in my view, whatever they do.

My experience of feeling invisible began with menopause. We no longer draw the male gaze. I don't actually mind -- as Gloria Steinem said when she turned sixty, we can stop playing female impersonators. She is now 80 too. I wonder if she'll be asked to model for an upscale clothier.

I too grew up as a child reading my mother's Vogue, with the mink coat campaign whose signature question was, "What becomes a legend most?" Not only Lillian Hellman but many older women posed glamorously--and perhaps received that (then) prestigious garment for doing so? That peculiar campaign in fact convinced me --not that I would be a legend--but that you had to be old to get the bourgeois goodies, the jewels, the furs, the houses, the sporty cars.

That funny illusion was a tiny part of the progress narrative that I concocted for myself, with a lot of help from the matriarchs and patriarchs in my family. But the progress narrative strengthened me, indubitably, to begin the hard work of critiquing decline culture.

Lynne Segal is right to point out the nastiness of some parts of the youthful cybersphere, but I would point out that most of the tropes and practices of the social media world are already passe and undergoing a re-evaluation about just how useful or significant they are (not very, on either account). It's a case of much ado about nothing. I don't know if Martin Amis's remarks were meant in earnest or jest, but he's hardly the place to go for people seeking wisdom or even common sense. The lad's novels are OK (but not much more than that), but when he's written non-fiction, he's tended to go off the deep end. His book about Stalin was nothing more than a hysterical plea for serious consideration from his old pal, Hitchens, and, as such ridiculous and, as serious social and/or intellectual history, totally redundant. In contrast, his Pop's writing about the old and the aging, no matter how nasty, was both insightful and humorous, regardless of his many stupid (well, make that unfounded or reflexive) beliefs.