In Toulouse

Jeremy Harding

I don’t know when ‘banlieue’ became a word in English, but it’s in a 1990 edition of Chambers as ‘precinct, extra-mural area, suburb’. Many people living in the rougher outskirts of France’s citiesprefer the expression ‘quartiers populaires’; others use the word ‘cités’: working-class neighbourhoods where architects, planners and commissioning bodies created huge, affordable housing projectshalf a century ago (long horizontal ‘barres’ and grandiose high rise set the tone). The rundown cités atthe margins of Paris, Marseille, Lyon and other major cities are once again under inspection after the 7-9 January killings: Amady Coulibaly, who murdered the policewoman in Montrouge and the fourJews in Paris, grew up in a dismal estate south of the capital. ‘Ghetto’ and ‘apartheid’, words already murmured whenever France talks to itself about these places, are now spoken openly. The primeminister, Manuel Valls, used ‘apartheid’ in a recent speech about urban segregation.

Mohamed Mechmache, an advocate for the banlieues, prefers to talk about zones of ‘discrimination’. That catches the feel of these places as you venture across the boundary (usually a ring road)into a discrete area of wilderness, set apart from the rest of France, where social injustice can thrive without major disruptions to the habitat. About one million people live in the worstmarginal neighbourhoods. Mechmache, fortysomething, the son of Algerian parents, grew up in a project on the eastern edge ofParis. I came across him a while back, between the 2005 riots in the banlieues and the 2007 presidential election: he was running a campaign for voter-registration.

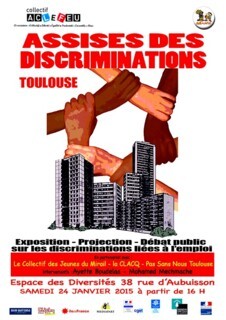

A few days ago he was in Toulouse, as part of a ‘discrimination assizes’ in the rougher parts of France. He repeated what he’d said just after the killings: the banlieues shouldn’t be turned intoreservoirs of blame. In 2005, he recalled, absentee parents and ‘polygamy’ were said to be the causes of the riots (rap was another); no point reminding his audience – many from the strickenprojects of Le Mirail, on the edge of Toulouse – that this was racialised blaming.

The assizes focus on prejudice and segregation in schooling, housing, jobs, health, and the lives of women and unemployed youth: all the key areas. Toulouse was billed as a session about work, butonce the audience pitched in, the meeting became a litany of injustices in the projects. There was also a hovering fear about the onset of draconian policing (people are ready for anything). NickyTremblay, the local activist who hosted the event, had warned a week or so earlier that asecurity blitz on the downtrodden cités was not the answer to jihadist violence. Hollande and Valls appear to agree with her: there’s no plan to re-enact the Battle of Algiers in the banlieues.

Mechmache and Tremblay would be relieved if they thought the new round of hand-wringing would lead anywhere. They doubt it. For years now, successive crises in the banlieues have made them thetarget of high-profile policy initiatives, generous central and devolved funding, and a string of zoning denominations, flagging up the need for better schools, decent living space and more jobs.In many places, including Le Mirail, outcrops of costly, civilised housing renewal are a credit to these interventions, yet even the best have left a light footprint.

The statistics are complicated. We know that 4.4 million people live in 751‘sensitive urban zones’ , and perhaps half of them survive on €651 a month or less. Beyond that, it gets difficult to say just how abject the worst places are. Last Sunday, on the back of aninterview with Manuel Valls, Le Journal du Dimanche – a paper of the right – had a stab at the number of destitute ‘quartiers populaires’. It cross-referenced three sources: priority areasin the nationwide urban renewal programme (200); ‘priority security zones’ with high delinquency rates and widespread safety fears (80); ‘priority education networks’ where Republican values arefoundering (around 1000). JDD concluded that there were 64 ‘ghettos’ in France. In any of them you’ll find it hard to earn a living (unemployment is around 25 per cent); as a qualifiedperson you’re half as likely as your counterpart in a better neighbourhood to find a job; one in three of you is an immigrant or descended from an immigrant; you have a fifty-fifty chance ofgetting your hands on more than €11,000 a year.

Demolition, renovation, dispersal and social engineering, even profiling for would-be tenants: all have been tried. So has trickle-down, with the introduction of tax-beneficial free trade zones(ZFUs) in bad neighbourhoods in the 1990s. Several speakers at the discrimination assizes in Toulouse denounced the ZFUs – which Hollande said he’d abolish – as a scam that brought businesses tothe banlieues for the fiscal exemptions; no one felt they’d honoured their side of the bargain by hiring local labour. ZFUs are now set to lose their status in 2020, but the old stand-bys for urbanregeneration are sure to remain.

The insoluble question is how to keep a mixed population in a difficult area under renovation. Jobs and incomes lead people away from the cités. Fresh arrivals are almost invariably poor. Theirpresence ensures that a neighbourhood where millions of euros may already have been spent remains a priority zone on several counts, and eligible for further funding. In essence it’s a process ofcontinuous wealth-transfer. For every person lifted out of difficulty, another moves into position and the funds keep flowing.

For revamped, muscular initiatives to stand a chance, they need to be drawn up in consultation with residents. In a recent mind-numbing survey it turns out (pp.168-169) that people asked about urban renovation in their areas like it well enough but don’t believe it makes much difference to their prospects. And 85 per centof respondents were never consulted before a scheme got off the ground, which riles half of them and leaves the other half shrugging their shoulders. Lack of consultation was the main theme in aninfluential report on urban policy co-written by Mechmache for the minister of housing in2013. It’s still a source of frustration in Toulouse: has anyone approached us for our opinion? Do they know we exist? Parts of Le Mirail have such a bad name that informed local opinion is discreditedby association or drowned in the babble of a high-level conversation going on elsewhere.

Last year the university in Le Mirail couldn’t bear the embarrassment any longer and changed its name from ‘Toulouse II-Le Mirail’ to ‘Toulouse-Jean Jaurès’. It’s a grandiose modernist campus builtin the 1960s by a partnership that included Georges Candilis,a protégé of Le Corbusier. Candilis had pushed for a university to top off the vast commission he’d been given for Toulouse’s cités of the future. Ten minutes on foot from the main entrance and youend up staring at a burger trailer with flat tyres on a godforsaken roundabout. Five minutes by car, through a world of grey-clad high rise and caged sports terrains, and you arrive at the site ofa prefab mosque – now just a hole in the ground in a perimeter of corrugated iron – where the 2012 scooter-killer MohamedMerah used to hang out. Merah was a low-level criminal raised in another part of Toulouse before he became a well-travelled disciple of jihad.

On my way out of Le Mirail I passed a pair of large, hyper-attentive young men in hoodies outside a shuttered Nan Kebab. It was just gone nine on a Sunday morning. I didn’t have the courage to askhow their day had been so far, or whether they’d ever prayed in the mosque before it was dismantled. I couldn’t imagine people further from God than those two edgy residents scanning the block foranything that moved. Yet the more I think about it, the less certain I get.

Comments