Mediterranean Oaks

Inigo Thomas

Fernand Braudel began work on The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II in 1923. He finished it in 1946. Three years later it was published in Paris, and a revised and expanded second edition appeared in 1966. In 1972, almost fifty years after he started it, an English translation was published.

Braudel’s opening sentence is a now famous declaration: 'I have loved the Mediterranean with passion, no doubt because I am a northerner like so many others in whose footsteps I have followed.' This was written a year after war was over, when the Mediterranean remained beyond the reach of most northerners. The Mediterranean is known for the novelty of its approach — ‘a history in which all change is slow,’ Braudel wrote, ‘a history of constant repetition, ever recurring cycles’. Yet some passages in the book must have produced more visceral reactions among its more northern readers in the aftermath of the Second World War:

The accelerated rhythm of summer life. With the coming of the luxuriant spring, often wet, with 'impetuous' winds... 'which bring the trees out in bud', the short-lived spring (almond and olive trees are in flower within a few days), life takes on a new rhythm. On the sea, in spite of the dangers, April is one of the most active months of the year. In the fields, the last ploughing is being done. Then follows the rapid succession of harvests, reaping in June, figs in August, grapes in September, and olives in autumn. Ploughing begins again with the first autumn rains. The peasants of Old Castile had to have their wheat sown towards mid-October, so that the young plants would have time to grow the three or four leaves that would help them withstand the winter frosts. In the space of a few months some of the busiest pages of the farmer's calendar are turned. Every year he has to make haste, take advantage of the last rains of spring or the first of the autumn, of the first fine days or the last. All agricultural life, the best part of Mediterranean life, is commanded by the need for haste. Over all looms fear of the winter.

Oliver Rackham was another northerner who loved the Mediterranean. The physicist turned botanist and woodland-enthusiast, who died last week, wrote admired books about landscape. Reviewing Rackham's History of the Countryside in the LRB in 1987, David Allen wrote about 'the remarkable figure of Oliver Rackham, a throwback to earlier centuries in his solitary, single-minded endeavours made at the expense of an orthodox – and secure – career'. Richard Mabey wrote about Rackham in the Guardian last weekend: ‘No one had a more crucial impact on a whole generation’s ideas about ecology and history. For Oliver, woods weren’t abstract entities; they were symbiotic networks of carpenters, beetles, deer, land-thieves, lichens, pollards, surveyors and toadstools.’

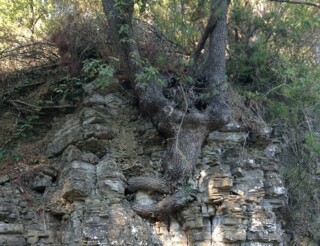

The Nature of Mediterranean Europe: An Ecological History, which Rackham co-wrote with A.T. Grove, aimed to correct an assertion made by Braudel and other historians: that the land was becoming inexorably unusable because of human activity: farming, foresting, deforesting etc. Rackham and Grove exposed this as a myth. 'Today,’ they wrote (in 2003), ‘writers on political ecology feel obliged to cite the “typical” Mediterranean landscape as an example of “massive degradation”. Scrub and scattered trees are interpreted, without evidence, as the “debased forms of the forest”.’ Rackham and Grove wrote about some of the more indestructible flora of the Mediterranean, such as the fire-resistant Quercus coccifera, which thrives on rock.

Yet Rackham recognised more permanent dimensions to human activity in the Mediterranean, that 'history of constant repetition, ever recurring cycles’. In The Nature of the Mediterranean Europe. Rackham and Grove wrote about the arrival of autumn:

Late September is a good time to be in the Mediterranean. The last charter flights take off; the beaches empty; departing tourists are sped northwards by the first storms. Parasols are stacked away, kiosks shuttered, boats pulled high up the shore... In plastic green houses, winter salad crops are watered and sprayed. The first heavy rain, always a joyous event, refreshes city and village. At last there is room to park a car. The local language reasserts itself. Sheep trot along the village street; in coffee houses wood stoves and spirit stills are reassembled from storage and fired up; young men load their shotguns and set out for the bush.

This May, there will be a daily train to Marseille from London, which doesn’t make London any closer to the Mediterranean: olives won’t flower a few days after the almonds blossom. But it is nice to know it will be there.

Comments