Episode Five: Flatliners

John Lanchester

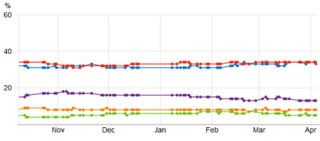

The BBC has a handy electoral poll tracker on its website. Here’s where we are:

I’ve never seen polls like that. The thing which really stands out is that nothing stands out. They are as flat as the flattest of flatnesses. Five months ago, on 7 October, Labour was on 34 per cent and the Tories on 32. In the latest polls, Labour are on 33 per cent and the Tories on 34. That small advantage is not stable, though. The parties are passing the tiny lead back and forth between them like dope-smokers conscientiously sharing a joint.

Most people don’t think much about party politics. To get their attention you need, in the language of the pros, to ‘cut through’. For all the noise and kerfuffle, this election hasn’t. It isn’t self-evident why, and no doubt this very fact will be the subject of study for some time to come, but there are a number of possible reasons. One of them might be that the parties and their leaders are so boring and so small, and arguing within such narrow margins of neoliberal consensus, that the electorate just can’t be bothered to think about them. The problem with that line of argument is that something very similar could have been said about many other elections, without there being this same picture of non-engagement and stasis.

The fixed-term parliament might be playing a role. When the government can choose the timing of an election, the electoral game turns on picking a moment of waxing popularity. If the right moment doesn’t come, the government hangs on as long as it can, in the hope of a convenient accident (small war, big scandal). When it clings on like that, recent history suggests, it tends to lose. Here are the last eight elections, arranged in order of how long the government waited before calling it:

| 1997 | 5 years 1 month | lost |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 5 years | lost |

| 1992 | 4 years 10 months | won |

| 1979 | 4 years 7 months | lost |

| 2001 | 4 years 1 month | won |

| 1983 | 4 years 1 month | won |

| 1987 | 4 years | won |

| 2005 | 3 years 11 months | won |

The general rule seems to be that the longer a government is in office, the more likely it is to lose. The exception is 1992, when everyone thought Labour would win, until the first exit polls came through. (I remember that vividly because my wife and I went over to a friend’s house to watch it. We set out at 9.50 expecting to arrive at a party, and walked through the door at 10.05 to an atmosphere of recent bereavement.)

The causation doesn’t run from longevity to unpopularity, but the other way round: governments which were worried about losing stayed in office as long as they could. The election always came as an event whose timing had been determined by a trajectory of popularity and public feeling. Not this time, though. The date has been set for five years, and the polls look set too: stuck down, glued in place. We’ve seen this one coming a long way off. The parties haven’t had to scramble and cobble together a pitch for our attention. Maybe that’s a problem: our opinion of the contestants is all too fixed and definite and well-known.

I wonder if another contributing factor is social media, especially Twitter. Twitter is the speediest and most powerful news source that there has ever been. But it’s very very easy – too easy – to arrange your supply news and information and opinion so that you only hear from people who already agree with you. You can’t be on Twitter without screening out trolls and morons, and it’s a simple matter to cross over from that to screening out all differing viewpoints. You can confirm a viewpoint or perform an allegiance in 140 characters, but you can’t change somebody’s mind. If we can read one thing from that poll tracker, it’s that people’s minds aren’t being changed. It’s almost as if, to adapt Jean Baudrillard, the general election is not taking place.

Comments

In fact I think these days I see more comment via Facebook and Twitter from news sources I wouldn't previously have looked at. Often they tend to be the more swivel-eyed rantings offered up by my network for ridicule and outrage, but not always. In any case, unless you are genuinely undecided in your voting intention, and interested enough to want guidance, then even 140 pages of comment won't change your mind, let alone 140 characters.

Personally I think the lack of 'cut through' and the narrowness of policy variation between the two main parties is more significant. Such cut through as has happened took place some time ago. UKIP snared the support of the 15% of the population who blame foreigners for everything. Even in Scotland the SNP's cut-through was achieved in the referendum and their domination over the collapsed Labour vote has also been a flat line on the graph since September.

The true picture of non-engagement will come from the turnout. Will more than two-thirds of the electorate actually give enough of a toss to cast a vote? In such a close run election if there is no significant increase over the 2010 turnout then there will be cause for concern.

I was expecting its support to drain away back to its traditional homes but I'm less confident of that now. It has held up much better in the opinion polls than I expected but, who knows, maybe the reversion will come in the voting booth.