At Victoria Miro

Alice Spawls

Francesca Woodman’s early death, at the age of 22, has cast a long shadow over her work. In the preceding years (her father gave her a camera when she was 13), especially those spent at Rhode Island School of Design and in New York, she produced a wealth of images: there are more than 10,000 negatives. This leaves a problem for her estate (her parents, George and Betty Woodman, are both artists) and her curators: it has been left to others to select, group and edit her archive. Eight hundred prints have been made, of which fewer than two hundred have been exhibited.

Woodman’s fame has grown enormously since the first, posthumous exhibition in 1986, but critics and fans have returned continually to the same tropes: her suicide, her interrogation of the male gaze, her surrealist imagery. The work lends itself to feminist critiques: she was often the subject of her photographs (‘because I’m always available’) and often nude, dissecting the body or manipulating flesh with tape and pegs. Zigzag, at the Victoria Miro gallery in Mayfair until 4 October, shifts the focus to the formal aspects of her work through a series of prints that use the zigzag as a compositional motif; ten have never been shown before.

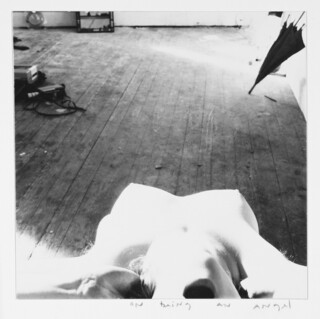

When you start looking for them, zigzags are everywhere: the bend in an arm or leg extending from the body, slanting light, angles between furniture, floor and wall. In one large diazotype print, the shape extends through a series of 13 images, from first-position feet to the V-neck of a dress, legs open in a midair jump, arms and backs, a pattern on the wall. Woodman’s use of light and props – not only the mirrors and dresses but the background detritus of petals, paper, rubble – is endlessly experimental. The foreground of On Being an Angel (1976) is dominated by a zigzag of exposed breasts, illuminated to blinding white, which becomes part of the play of light across the floor. The black umbrella propped against the wall behind looks like an arrow. Woodman’s debt to Man Ray is clear: the imagery, but also the sumptuous blacks, which seem to coat the white figures, and her restless gaze. The New York fashion world saw little in her work when she sent her portfolio around in 1979; it’s hard to imagine now.

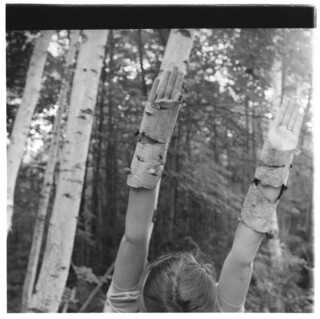

The exhibition emphasises Woodman’s playfulness. Two arms wrapped in silver birch bark mimic the trees of the forest behind; from a distance you can’t tell the arms for the trees. But more than anything else she explores the textural qualities of her medium. In one photo a girl in a 1950s dress lies supine on the floor, a black snake across her arm – but what strikes you is the heavy, shimmery brocade of her dress on the patterned carpet. In Untitled, New York (1979-80) a black fox fur, fuzzy around the edges, hangs on a white wall while a girl in a black dress mirrors its form – arms held overhead – but in a smooth, fitted black dress. In another the blurred bedspread in the foreground is portrayed with greater clarity in the mirror set on the floor behind it: the camera is not a true reflection, it seems to say. Woodman’s compositions, so carefully orchestrated and starkly lit, are unsettled by the ambiguity of materials: carpet looks like grass, fabric like paper, mud is shiny-hard. Blurred bodies in motion – soft greys of moving flesh – look strangely vulnerable in the uncertain world they occupy.

Among the most beautiful images are two in which Woodman’s classical sensibilities combine with her inventiveness. The first, an interior from a series of related photographs, centres on an unhinged door positioned at a seemingly unsustainable angle between wall and floor. The door, leaning against a white wall, descends to shadow and meets a curved arc of shadow on the floor, while its doorway stands empty and faintly illuminated, revealing two closed doors beyond. Unlike the other photos in the series it doesn’t contain a crouching figure; instead the door itself seems animated.

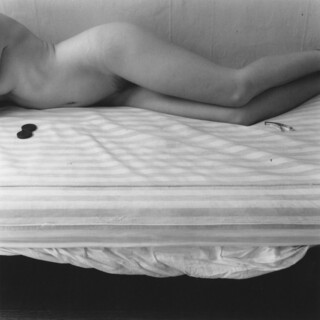

In the second a reclining nude, cut off at ankles and chest, occupies the top third of the picture. She is pushed back to the furthest reach of the image; an expanse of striped sheet takes up the centreground. The wrinkles of wallpaper, flesh and material correspond in a strangely tactile relationship: the thin paper, the solid flesh, the way the flesh over the ribs is echoed in the creases of sheet going against the stripe. But strangest of all is the way the undersheet in the foreground emerges from the taut topsheet and descends, a complex unfurling against a supreme blackness.