The Freedom Principle

Adam Shatz on the New York Art Quartet

Nearly a half century ago, the New York Art Quartet had its debut at the Cellar Café on the Upper West Side. The occasion was the October Revolution, a four-day music festival curated by Bill Dixon, the visionary trumpeter, founder of the Jazz Composers Guild, and director of jazz programmes at the United Nations. The New York Art Quartet – the subject of Alan Roth’s absorbing new documentary, The Breath Courses through Us – represented the next wave in avant-garde jazz after Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor. One of the first leaderless, simultaneously improvising ensembles, it embodied what John Litweiler has called the ‘freedom principle’. Yet it showed that freedom did not have to mean the propulsive ‘fire music’ that Coltrane’s followers were playing, or the screaming, protopunk cacophony for which the label ESP became legendary. The New York Art Quartet’s music was lyrical and somewhat elusive, open-ended in an orderly way, full of subtle effects that people didn’t tend to associate with free jazz.

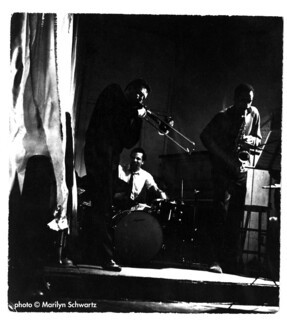

The New York Art Quartet featured John Tchicai, an Afro-Danish alto saxophonist; Roswell Rudd, a Yale-educated Jewish trombonist who’d started out in Dixieland revival bands; Milford Graves, a drummer from Queens with a background as a Latin American percussionist; and several rotating bassists, including Lewis Worrell and Reggie Workman. It came together at the downtown loft of Michael Snow, an artist from Toronto who was also an accomplished jazz pianist. Snow had just made a short experimental film, New York Eye and Ear Control, with a soundtrack improvised by Tchicai and Rudd, as well as Albert Ayler, Don Cherry and others. Tchicai and Rudd were performing at Snow’s place one evening when they were introduced to Graves, who combined staggering technical prowess with an extraordinarily fluid sense of time. Graves sat in with the band, filling in for J.C. Moses, a more traditional timekeeper who’d been promised the drummer’s chair. Unfortunately for Moses, the chemistry was perfect. On their self-titled first album, the quartet was joined by LeRoi Jones, soon to reinvent himself as Amiri Baraka. He read his incendiary poem ‘Black Dada Nihilismus’, and became the quartet’s honorary fifth member and intellectual mentor.

The band wasn’t around for long – hardly a year. But it was the year in which the Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts were passed, Malcolm X was assassinated and the call of Black Power raised; John Coltrane recorded A Love Supreme, and Baraka’s Dutchman, about a fatal encounter between a middle-class black man and a white temptress on the subway, was performed at the Cherry Lane Theatre. Greil Marcus once observed that a band is an image of community, and so it was with the New York Art Quartet: a multiracial, international ensemble whose members were on an equal footing.

The Breath Courses through Us, which was recently shown at the Anthology Film Archives, is largely based on interviews Roth conducted with Tchicai, Rudd, Graves, Workman and Baraka in 2000 (when the band briefly reunited to open for Sonic Youth). The film is dedicated to Tchicai, who died in 2012. Born in 1936 in Copenhagen, he was the son of a Congolese father and a Danish mother. His sound was light and airy and owed much to Lee Konitz. He thought of the New York Art Quartet’s contrapuntal dialogues as a jazz version of Beethoven’s string quartets. Tchicai met Bill Dixon and the tenor player Archie Shepp at a Communist youth festival in Helsinki in 1962. ‘Shepp was wearing some kind of black fez and Dixon had his black beard and big hair… Normally you didn’t see black people wearing Afros in those days.’ They urged him to come to New York as soon as they heard him play. When he arrived a year later, he was shocked to find that the musicians he admired weren’t living in ‘big houses’.

Things weren’t much better when Tchicai returned to Copenhagen in 1965. (He tried to persuade his bandmates to join him, but Graves had a wife and four children.) Unable to find work, he turned up at the state radio station, walked into the cafeteria, grabbed a tray of glasses, and shattered them on the floor. The incident set off a scandal in the Danish press. He landed a recording contract and a radio gig. But he missed New York and the vibe he’d had with Graves and Rudd. After a spell teaching in California he moved to Perpignan, where we see him in Roth’s film practising standards, a reminder that Tchicai was steeped in traditional song forms.

The band’s other members also went their own ways. After Macolm X’s assassination, Baraka left Hettie Jones, his Jewish wife, and their two daughters, and moved to Harlem. He ran the revolutionary nationalist Black Arts Repertory Theater, where the New York Art Quartet, an interracial ensemble, was not welcome. He then moved to Newark and rejected nationalism in favour of Marxism-Leninism. But for all his ideological zigs and zags, until his death in January this year he remained faithful to the music, and to his belief that it expressed better than any artistic form the creativity, history and philosophical outlook of Black America. Graves, out of his Queens apartment, became a kind of shaman with drumsticks, using percussion and herbs to heal people. Rudd settled in the Catskills, worked as an assistant to Alan Lomax, and developed an interest in the music of Mali. Reggie Workman, who played with almost everyone on the jazz scene, made a living as a professor at the New School. When they sit around the table before their 2000 reunion concert in Roth’s documentary, they have a lot of catching up to do: they’d had virtually no contact since Tchicai returned to Copenhagen.

The New York Art Quartet only made a few records, but a rich trove of unreleased material remained in the vaults. Ben Young recently released this work in a boxed set, Call It Art, on his label Triple Point Records. It includes five vinyl records, featuring historic performances by Baraka (reading a poem about Allen Ginsberg). Some of the music is glorious, particularly Tchicai’s rubato ‘Ballad Theta’, a cousin of Ornette Coleman’s ‘Antiques’; some of it is scrappy, as you’d expect from out-takes. The accompanying book, though, is an often revelatory work based on extensive archival research, illustrated with reproductions of concert announcements, newspaper clippings and evocative photographs by Larry Fink and others. Young believes that the band heralded a radical new development in free music, not least for having decided to ‘call it art’, not jazz. Graves, he argues, was the pivotal member, creating a style of free-time drumming that provided a ‘bed’ for improvisation – more like a water bed, moving to accommodate whoever lay on it. Call It Art is priced like an objet d’art ($340 for the signed copies; $192 unsigned), but it’s one of the most important jazz releases in recent years. It’s also a major contribution to American cultural history.

The Breath Courses through Us and Call It Art might be seen as companion pieces to Witness, a show about American art and the Civil Rights movement at the Brooklyn Museum, curated by Teresa Carbone and Kellie Jones, the eldest daughter of Baraka and Hettie Jones (until 6 July). The selection of artists is strikingly inclusive, aesthetically and racially: Rauschenberg and Bearden, David Hammons and Norman Rockwell, Betye Saar and Andy Warhol, Bob Thompson and Philip Guston, Jim Dine and Barkley Hendricks, Jack Whitten and Ben Shahn. But what the show underlines with particular force is the emergence of a vernacular modernism among African-American artists of the Civil Rights generation. This was a visual analogue of the New York Art Quartet’s music, and of the writing of Baraka and other members of the Black Arts movement. These artists embraced and indeed helped pioneer the innovations of postwar art, but they also wanted to use these innovations as a way to express themselves politically. Many combined abstraction and figuration, refusing to see them as a forked road in the history of Western art. At the centre of Jack Whitten’s stark painting Birmingham, a torn-up piece of aluminum foil reveals a hidden photograph of the church bombing: a sliver of documentary horror embedded in a sombre black monochrome canvas. Like much of the best work in Witness, like the New York Art Quartet’s first record, Birmingham was made in 1964, the year that avant-garde black American modernism announced its birth, in a cry that was equal parts hope and rage.