Libya’s Ancient Borders

Josephine Quinn

The port of As Sidr is on the Gulf of Sidra, the enormous bay biting through at the junction of Libya’s three major geographical regions: to the east, the lush agricultural land of Cyrenaica; to the west, the drier urban coastal strip of Tripolitania; to the south, the Saharan Fezzan. This has always been frontier territory, and often in dispute.

As Sidr has been held since last summer by rebels demanding autonomy for Cyrenaica. Last Saturday, the North Korean-flagged tanker Morning Glory docked at the sport, loaded 234,000 barrels of oil and set sail, evading the Libyan navy. The prime minister resigned. Last night, US Navy Seals boarded and took control of the ship in international waters south-east of Cyprus.

The faction that controls As Sidr defines Cyrenaica as stretching beyond Surt, 200 kilometres to the west. Under Italian occupation, As Sidr itself fell just within the colonial province of Tripolitania: when the Italians built the Via Litoranea, the first tarmac road around the Gulf of Sidra, they put up a monumental arch to mark the border between Tripolitania and Cyrenaica 25 kilometres east of As Sidr, at Ras Lanuf.

‘Marble Arch’, as British soldiers later called it, was officially unveiled by Mussolini in 1937 and blown up by the Gaddafi government in 1970. It was decorated with bronze statues of two ancient Carthaginians who had died to establish a frontier there. After a series of territorial disputes, Sallust says, the Greek colony of Cyrene and the Phoenician colony of Carthage agreed to recognise a boundary. Runners would be sent out from each city at the same time. The border would be established at the place where they met. The Carthaginian Philaeni brothers ran faster than the Cyreneans, so they met much closer to Cyrene than Carthage. The Cyreneans accused the Carthaginians of cheating, and said they would only agree to fix the boundary at that point if the Carthaginians would agree to be buried alive there. The Philaeni accepted the deal, and Carthage built altars in their memory on the spot.

The 'altars’ have been identified with the two small heights of Jabal Ala, 25 kilometres east again of Ras Lanuf, the first change of relief visible to passing ships. The later story of the Philaeni brothers presents not only a Carthaginian version of events, but also of the frontier: Strabo put the border between Carthage and Cyrene considerably to the west, at ‘Euphrantas’ tower’ – modern Surt. When the Romans invaded they accepted the Carthaginian story, making the altars the boundary between their provinces of Africa and Cyrenaica.

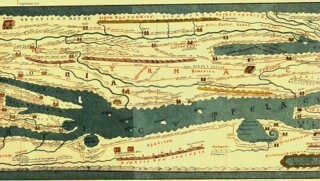

Perhaps the Carthaginians or the Romans put up real altars at Jabal Ala: this is certainly how the ‘Altars of the Philaeni’ (Ar(a)e Phil(a)enorum) are depicted in the schematic Roman map of the world known as the Peutinger Table. But this late antique document, preserved in one medieval copy, doesn't depict the reality of the ancient landscape in any period so much as a world of the collective Roman imagination. And in this section it illustrates above all the fear inspired by the Gulf of Sidra, famous for its sandstorms, serpents and shipwrecks. No towns are shown, or even buildings: the Altars are the only landmarks along the desolate coastal plain, and the gulf's curious curly tail vividly represents what Pomponius Mela called the ‘reversing movements’ of the tide there, which creates a strong clockwise current as it rises, and anticlockwise when it falls. These reversing movements may explain why the much smaller naval vessels blockading the Morning Glory failed to chase it down as it sailed into international waters last Monday.