At Sea

Alice Spawls

At Southwold harbour the other weekend the fishermen were doing a busy trade, selling lobsters to visitors who had come for the sunshine and the sea, though the sea was still cold and grey, turning murky brown as the tide swelled with silt and pebbles. The crag that makes up much of the Suffolk coast is the softest and youngest rock in the UK, and especially vulnerable to erosion. Southwold is very nearly an island, cut off by the River Blyth to the south-west and Buss Creek to the north. Since the Environment Agency announced plans to stop maintaining the estuary in 2007, local groups have been repairing breaches, preserving the freshwater marshes and maintaining the 400-year-old clay walls along the Blyth (known as ‘slubbing the banks’).

Just down the coast is the village of Dunwich, one of England's busiest trading ports before it was swallowed by the sea. In truth the town was surrendered: three nights of storms in 1286 swept away its harbour. The river found a new route to the sea further north, at Walberswick, and the inhabitants gradually moved away, abandoning the sea defences their ancestors had maintained for centuries. Turner painted the ruins of All Saints’ Church in 1830 as a ghostly white transparency, foreshadowing its eventual crumbling descent, arch by arch, into the sea.

Simon Read, whose technical drawing of Fakenham salt marshes is included in The Power of the Sea (at the Royal West of England Academy until 6 July), has been studying the disappearing coastline of East Anglia since 1980, making an annual pilgrimage on Jacoba, his Dutch barge. His observations have fed back into coastal protection schemes not too dissimilar from the ones Dunwich villagers once used, such as the 90-metre barrier to counter the tidal erosion of Sutton salt marsh on the River Deben. The barrier is made of 62 screens of mesh and brushwood, absorbing tidal energy and controlling silt deposits. But other parts of the coast won’t, or can’t, be spared: the decommissioned lighthouse at Orford is expected to last perhaps seven more years before the sea claims it.

The sea has become an increasingly toxic and depleted resource. The opportunity to paint a vast amount of sky and interpret the effects of light on air and water made uncharacteristically daring colourists of the British: there’s a bright pink sky in John Brett's Dramatic Christmas Morning, 1866 and pale orange over a turquoise sea in John Miller Marshall's For Those in Peril on the Sea (c.1913), but contemporary marine art is more likely to mean photographs of washed-up gulls, their stomachs bursting with plastic.

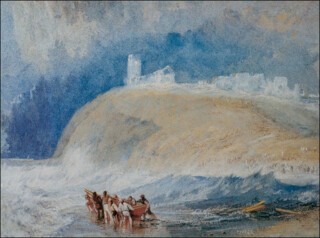

Turner and the Sea, a recent exhibition at the Greenwich Maritime Museum, included Claude Lorrain's rarely exhibited etchings Harbour Scene with a Lighthouse and Portico and The Shipwreck (on Wednesdays you can ask to see them at the British Museum). Turner, who greatly admired Claude, had the advantage when it came to printmaking: the development of mezzotint, the first tonal method, allowed him to replicate his atmospheric gradations in ink, while Claude had to rely on etched lines. But we profit from these limitations: the etchings reveal the draughtsman behind the colourist. The Shipwreck is a departure from Claude's usual marine scenes, the early morning idyll of The Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba and the luminous calm of Seaport at Sunset. A pyramidal tempest of wave and rock rises up to a ruined tower; a ship struggles against the surge; in the foreground, three perilously exposed figures strain on a rope. The hatched lines create a series of volatile diagonals: the masts of the ships, the sheet of rain and the crashing waves oppose the labouring figures and their taut rope, which echoes the angle of their dubious promontory. The delicately feathered peaks of the crashing waves are especially lovely.

Andrew Brink’s Ink and Light: The Influence of Claude Lorrain's Etchings on England shows how masterfully Claude could manipulate etching into a tonal medium. Le Soleil Levant (1634) seems to emit its own rays. Areas of unmarked white sunlight are set off by the lightly etched patches of grey cloud and the contrasting silhouettes of men and boats. The prints return to his favourite themes: travel and its perils, chaos and refuge, the return to safe harbour and pastoral idylls. The drama of The Shipwreck is rarely centre-stage in Claude; danger and uncertainty play out in small scenes, with the participants, like the viewer, distracted and dazzled by their awesome surroundings. It’s easy to see why Turner responded to him – the light, the expansiveness, the incidental relationship to narrative – though Turner’s sublime is less ambiguous about menace and confusion, incorporating them into the natural brilliance of a scene.