‘The Little Red Schoolbook’

Jenny Diski

In 1971 I had just finished a teacher training course and was teaching at a comprehensive school in Hackney, now a flourishing educational establishment, but then a place where the sixth form consisted of the highest achievers doing their CSEs in the near forlorn hope that they might get work in a bank. When I first started teaching there, none of the kids had ever taken A-levels or gone to university. It was a place where good teaching really meant doing social work and trying to pump up the kids’ ambition and interests (it was an all girls’ school) beyond getting free from school and family by getting pregnant. At the same time, I was involved in a freeschool I’d started with a friend, for seven siblings and a couple of others from the locality I’d got to know from their hanging about in the local playground, and whose real social worker had come to me and said that unless I invented a school for them over the weekend, they would be taken into care for non-attendance at school.

We got the thing up and running on paper over the weekend, and in reality over the next few weeks until, eventually, it was funded by Camden Council (thank you Frank Dobson), and inspected and found to be ‘efficient’ by Her Majesty’s Inspectors of Schools. It was not a freeschool that Gove or Toby Young would recognise. We ran it by committee, which included us, the kids and anyone local with any interest or expertise in education. We piled the kids into one of the teacher’s Morris Minor and took them off to galleries, films, on country holidays (art, English, geography). We gave them money to shop for and produce their daily lunches (home economics, maths). We talked about sex, politics, how systems worked and wrote letters with them to various MPs and local councillors for funds (biology, civics, history and English). It was chaotic, but a memorable time, which gave some of the kids their first taste of having something created especially for them, as well as a sense of obligation and isolation from the rest of their peers that they found quite difficult to deal with – one of them wanted to go back to regular school so that she could get ‘back to bunking off like everyone else’.

Some of the teachers were local people with particular skills – an architect, a mechanic, people who cooked with the kids, others who took them to their place of work to show them how a working day went. The four paid teachers were educated, middle class, young, mostly graduates who were engaged with the children’s rights movement, were well to the left of organised politics, who were at the right age in that brief time when you could believe that it was really possible to change people’s lives by thinking with them about what education was for.

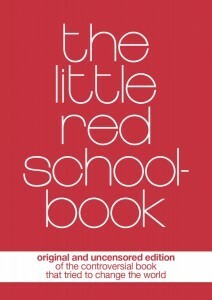

This week sees the publication of The Little Red Schoolbook for the first time in its uncensored form since it was first set to be published and banned in the UK in 1971. The Little Red Schoolbook, little and red in honour of Mao’s Little Red Book, was written by two Danes (obviously!). It offered an alternative world view to the young still at school. It discussed Homework (Make your homework useful), Teachers (Teachers are dogs on leads, too), How to have influence (It’s difficult to influence someone who’s afraid), Streaming (Can streaming be changed?), Sex (Masturbation, Wet Dreams, Child Molesters or ‘dirty old men’, Intercourse and petting, Addresses for help and advice on sexual matters), The system (Discrimination against girls, School councils, About solidarity). It frightened the life out of the establishment. Ross McWhirter claimed the book to be obscene and seditious. Elizabeth Manners, a headmistress who was a witness for the prosecution successfully demanded by Mary Whitehouse, claimed: ‘It is not true to say that masturbation for girls is harmless, since a girl who has become accustomed to the shallow satisfactions of masturbation may find it very difficult to adjust to complete intercourse. This should be checked, but I believe it to be a fact.’

It’s almost as much fun now as it was then to rediscover how scared such people were of releasing information to the young. They were running around squealing about no end of terrors from The Little Red Schoolbook, to the Schoolkids’ Oz edition, to those who were trying to alter teaching to take account of the pupils’ lives and needs, rather than the needs of capitalism for a workforce none too well educated. They succeeded in preventing an unexpurgated Little Red Schoolbook, were upheld in the European Court of Human Rights, and when the Oz editors were arrested, the worst thing they could imagine happened to them – the cutting of their long hair. It’s hard to credit the meanness and stupidity and the fear of social turmoil that wafted around then. They needn’t have worried. It turned out it was only their funk that gave us the idea that society might change if we gave it a push in the proper direction. Though we huffed and we puffed, as the surviving author of the Little Red Schoolbook says:

Fortunately today, the Victorian/authoritarian school is no more. More sophisticated methods to discipline and standardise children have been carefully put into place. Children have been placed into a competitive arena. Education is no longer a personal process of forming a child into an adult. Now it is examination, classification, a standardised curriculum, intellectualisation, league tables etc. Gone are the creative subjects. It is ‘Beat your buddy.’ The pupils are the losers. Unfortunately, I still believe the book is needed.

When he gave the new uncensored edition to his grandchildren aged between 18 and 23, they said: ‘Grandpa, you’re a bit way out!’ It makes me want to cry.

Give the new book to any child you know. The worst that can happen is that they will learn that ‘whatever the reasons may be, and however many people you may go to bed with, it will have consequences for each person … The only way to avoid unforseen consequences on sexual relationships is for both people to be honest with one another about what they are looking for … People who warn you against both strong feelings and sex are as a rule afraid of both. They haven’t dared to do very much themselves, so they don’t know enough about it. Or their own experiences of sex may have been bad. Judge for yourself, from your experiences.’

What dear, innocent, undangerous days they were.

Comments