In Thessaloniki

Yasmine Seale

‘Collectors,’ the collector George Costakis observed, ‘are like madmen.’ Costakis was the son of Greek emigrants who settled in Moscow at the turn of the 20th century and grew wealthy on tobacco. He made himself indispensable — as chauffeur and general factotum — to various embassies, who paid their staff in hard currency rather than worthless roubles. At first his madness took familiar forms: opulent carpets, Russian silver, Old Masters by the dozen. But the outbreak of war disrupted his livelihood, and the bibelots were sold off. It was just as well: tired of still lifes (which, he found, all ‘faded to a grey-brown blur’) and piqued by a chance encounter with a different sort of painting, a carcass of riotous colour and disjointed form, Costakis changed tack. He devoted the rest of his life to unearthing masterworks of the Russian avant-garde.

Within ten years he had amassed the greatest collection of their work in existence. Figures are hard to come by — he kept no catalogue, no record of transactions — but there are inklings of its scope: when 1500 works on paper were stolen from his apartment, the loss was not significant. In size, his collection far outstripped Peggy Guggenheim's, or Gertrude and Leo Stein's, or the entire Armory Show of 1913.

Abstract painting, verboten under Stalin, was virtually absent from the market, and most of the works were bought directly from the artists or, more frequently, their heirs. (Bruce Chatwin, who visited in the 1970s, called it ‘his private archaeological excavation’.) Costakis later wrote that the collection was ‘built with love’, but his enthusiasm met with obstacles: the difficulty of tracking down the works, the neglect they had suffered, the disbelief of widows (‘What do you see in them?’). In a dacha outside Moscow he found a Constructivist masterpiece being used to close up a window; the owner wouldn’t part with it. He dashed to the city to fetch a piece of plywood the same size, ferried it back to the dacha, and swapped it for the painting.

After a series of misfortunes Costakis decided to emigrate to Greece. Before he went, in 1977, he donated to the Tretyakov Gallery one of the largest and most important gifts of art that any museum has received in the 20th century — only part of his collection. He was allowed to leave with the other part, which was bought by the Greek state after his death. Today it is housed in Thessaloniki, in a former monastery on a hill above the sea. The mass of the collection is hidden from the public, but periodic exhibitions along loose themes — light, black, seasons, space — allow glimpses of its riches. Last month, when I visited, the theme was women. The triumph of the avant-garde is unthinkable without them — a Futurist poet described them as ‘real Amazons, Scythian riders’ — and they were instrumental in the movement’s expansion into utilitarian production and industrial design. Some of the boldest applications of abstract art to practical life were the work of Lyubov Popova. The respect she commanded among her peers and her prominence in the avant-garde make her one of the exceptional success stories in the history of women artists before the 1970s.

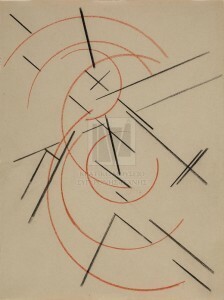

Popova’s short career (only a dozen years of mature work, 1912-24, of which the last four were the most productive) reads like a history of painting: as a very young woman she is in Italy, admiring Giottos. She paints traditional studies of trees and human figures. Soon she is working in the Moscow studio known as the Tower with Tatlin, and a season in Paris immersed in Cubism emboldens her to strike out into abstraction. She showed at the 'First Futurist Exhibition of Paintings' in Petrograd in 1915, and at the 'Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings' later that year, to which she contributed ‘sculpto-paintings’ that used found materials to create three-dimensional reliefs. Her interest in Russian icons embraced not just the holy image but the wood on which it was painted.

In 1921 she did away with the canvas, painting scaffolded structures and planes of high colour on an unprimed wooden board, leaving large areas bare. Her bold exposure of rough plywood finally abolished the long reign of the easel, and that year she joined Rodchenko in proclaiming the ‘end of painting’. Instead she turned her energy to what Alfred H. Barr, the first director of MoMA, called ‘an appalling variety of things’: she drew abstract patterns for embroidery, and models for proletarian furniture. She designed silk scarves and odd, unstructured dresses; murals for co-operatives and unions, and banners for poets’ clubs; posters against prostitution and illiteracy; stage sets and musical scores; covers for Questions of Stenography, film journals, and a book of odes to the Eiffel Tower. She decorated the Moscow City Council building. She drew maps and plans for ‘the city of the future’. Her contemporaries called her the ‘artist-constructor’.

The exhibition’s singling out of women artists for special treatment would have seemed odd to Popova and her peers; Constructivism’s emphasis on collective creativity, utilitarian art forms and the language of technical expertise aimed to make sexual difference irrelevant. Yet Costakis might have been pleased that ‘Lyubochka’, as he called her, was being brought to light once again. The painting he rescued from the dacha window was one of hers.