About a Ball

David Runciman

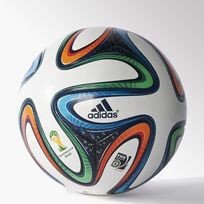

The star of this World Cup is called Brazuca. Who’s he? It’s the ball. It got its name in a poll of Brazilians in 2012: according to FIFA they chose it because the word ‘captures national pride in the Brazilian way of life’ (the second choice was the Bossa Nova, which would have been overegging it a little). The ball was designed by Adidas with the aim of avoiding the flaws of its predecessor, the Jabulani, whose erratic performance marred the 2010 World Cup in South Africa. Football designers often have a not-so-secret agenda to build something that will lead to more goals. The Jabulani was smooth and light, in the expectation that it would fly into the net. Unfortunately its aerodynamic features, combined with the high altitude at many South African grounds, meant it was more likely to fly away. The players didn’t trust their ability to control it over long distances, which contributed to the general ugliness of a tetchy, finickety tournament. Too many games ended up being played at close quarters.

This time round has been much better: more open games with more goals, more shots, more saves, and fewer yellow and red cards. It’s not all down to the ball, but a lot of it seems to be. The players trust this one. It moves in the air, but not wildly, more in little shifts and eddies within a predictable arc. The Jabulani behaved a bit like a boomerang. The Brazuca is more like a Frisbee. It has a rougher surface with deeper seams to give it greater consistency (the smoothness of the Jabulani made it more vulnerable to turbulence). Goalkeepers appear to trust it too. This tournament has been marked both by the number of long distance shots that have been on target and by the number of them that have been saved, which is what you want from a football match. The long passing has often been spectacular. The players look like they are enjoying themselves.

It also helps that the Brazuca is pretty. The fluid pattern of interlocking fingers looks lovely in slow motion, allowing the TV viewer to see the rotation on the ball and its path through the air. The ball is distinctive, but not so distinctive as to be distracting. Last season the FA, in a desperate effort to revive interest in their flagship tournament, introduced a pink ball for all FA Cup games. It certainly helped brand them: whenever I turned on the TV and saw the pink ball, my heart sank a little. You knew what you were watching: a Mickey Mouse tournament.

The Brazuca is already a badge of quality. Has there ever been a tournament, with so many moments that look lovely enough in slow motion to make you sigh? Take the loveliest moment of all, James Rodríguez’s sumptuous volley for Colombia against Uruguay in the recent round of matches. It had everything you could want from a goal. The quick glance goalwards that signalled intent. The first touch that brought the ball under close control. The perfect arc of the strike, until it crashed into the crossbar and then down and up into the net. A large part of the appeal of football, when it is at its most appealing, is aesthetic: the patterns that the players make with the ball against the static features of the pitch. With that goal Rodríguez signalled his arrival as a global fixture. But the ball was the star.

Comments