Promiscuity passim!

Dennis Duncan

As the Cambridge Edition of Virginia Woolf’s fiction slowly unfurls, this year will see the publication of Mrs Dalloway. It follows Anna Snaith’s edition of The Years (2012), which nestles Woolf’s 393-page novel in 600 pages of scholarly material: explanatory notes (144 pages), textual apparatus (220 pages), textual notes (50 pages), maps, chronologies, lists of illustrations, abbreviations, archival sources and editorial symbols, a bibliography and an (excellent) introduction.

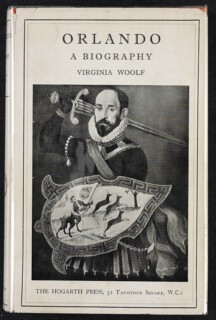

One paratext the Cambridge series doesn’t have, however, is an index. Novels as a rule don’t, of course, and although the scholarship heavily outweighs the fiction, Snaith’s edition of The Years is still at root a novel. The few novels that do have indexes tend to include them as part of a pretence that they’re something else: Pale Fire, for example, or Woolf's Orlando: A Biography (there's a nice comment, usually attributed to John Updike, that ‘most biographies are just novels with indexes’). Recasting her lover Vita Sackville-West as an ageless, gender-switching aristocrat, Woolf set out to blend the ‘granite-like solidity’ of fact with the ‘rainbow-like intangibility’ of personality. Orlando occasionally affects the dry tone of a scholarly biographer to tell the story of her life from Tudor times to the present; the novel’s index is part of this deliberate mixing of styles. Woolf is aware of the creative control that an indexer exercises in reframing a text. When she’d nearly finished the novel, she wrote to Sackville-West in a jealous temper, threatening to attack her in the index: ‘Promiscuous you are, and that’s all there is to be said of you. Look in the Index to Orlando – after Pippin and see what comes next – Promiscuity passim!’

Had Cambridge added indexes to their Woolf series, it wouldn’t have been without precedent. Walter Scott’s Waverley series had its principal incidents indexed by the 1860s; R.W. Chapman, supplied an index of characters and locations for his 1923 edition of Jane Austen’s novels; and Proust gets one in Gallimard’s 1954 Pléiade edition. Like the concordances to Shakespeare and the Bible, this type of indexing confers a kind of supreme canonicity. It implies that the incidents in these novels have acquired a value within the wider culture that exceeds mere fictionality; that we are likely to bring a different type of reading practice – non-novelistic – to these books, looking things up for reference, disregarding the context of the narrative in which they were originally set. Thus scenes are filleted and details tabulated for our convenience. What did Emma do at Box Hill? What does Proust say about Aldous Huxley? The index here is not the marker of a fact/fiction divide, but the sign of an uberclassic.

Digitisation has meant that the power of the concordance – the ability to search for any word or phrase – has been extended, no longer tied into individual works but part of the software platform, and as a consequence the index may no longer be the status symbol it once was. Still, there are other reasons to keep them, and the opportunity that a scholarly edition of Orlando represents – the possibility of a meta-index to the novel’s index – seems too good to pass up.

Comments

Hilary Mantel's tables of dramatis personae are de rigueur for the representative reader in danger of losing the plot.

Then there's the admirable practice of the editors at Le Livre de Poche for the Classics, providing the reader not only with scholarly Prefaces and illuminating Appendices, but with copious footnotes, which one can use or ignore at one's leisure. All this for a few euros.