At the Movies

Christopher Tayler

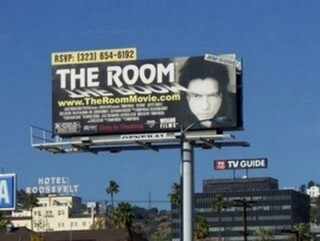

Publicity materials for The Room, an independently financed ‘emotional drama’, began to appear in Los Angeles in the spring of 2003. Postcards turned up in restaurant toilets, there were late-night TV ads, and on 1 April a poster featuring a giant mugshot of Tommy Wiseau – the film’s writer, director, producer and star – went up on a billboard on Highland Avenue in Hollywood, where it stayed for five years. Invitations to the premiere, held on 27 June, carried fabricated blurbs from trade publications. ‘Wiseau is multi-talented and mysterious,’ one read, ‘since he is a true Cajun from New Orleans.’ The Room played in a single LA theatre for two weeks, the minimum time required for eligibility for the Academy Awards. It took in $1800 against a reported outlay of $6 million and attracted such reviews as: ‘Watching this film is like getting stabbed in the head.’ This helped catch the eye of a couple of film students who worked hard to keep it alive as a local in-joke. Ten years later, thanks mostly to YouTube, there are regular late-night screenings in London and elsewhere.

The Room deals with a love triangle. Johnny, played by Wiseau, is a banker whom everyone agrees is a great guy. He lives in San Francisco with Lisa, his ‘future wife’ (never ‘fiancée’), whose beauty and sexiness are often remarked on by the other characters. Tiring of Johnny, she seduces his best friend, Mark, with tragic results for all of them. As far as the main plot goes that’s pretty much it, but there are many subplots, none of which leads anywhere or changes the course of the story in any obvious way. A teenaged boy called Denny, played by a 26-year-old, drifts in and out of Johnny and Lisa’s apartment. Early on, he tries to join them in bed, saying: ‘I just like to watch you guys.’ Later, Johnny saves him from an angry drug dealer called Chris-R. Lisa’s mother says: ‘I got the results of the test back! I definitely have breast cancer.’ (We hear no more of this.) And there are frequent bouts of male bonding in which Johnny and his pals toss an American football around at close quarters. Now and then the editing makes the ball seem to take a few seconds to travel six feet.

Unlike a lot of films touted by so-bad-it’s-good types, The Room really is consistently entertaining, mostly because of the scene construction and dialogue:

JOHNNY [entering with flowers]: Hi, babe. These are for you.

LISA: Thanks, honey. They’re beautiful. Did you get your promotion?

JOHNNY: Nah.

[Pause. A vase materialises in LISA’s hand as she crosses the room and sits down.]

LISA [coldly]: You didn’t get it, did you?

Every moment is like that, and the range of wrong notes is so extensive that the effect doesn’t quickly get stale. All the same, the film’s long-term reception trips a couple of alarm bells. Not surprisingly, the fan culture that’s grown up around The Room involves a lot of jeering at the cast’s inadequacies. Wiseau, the production’s all-controlling mastermind, is unquestionably fair game, but after a while it feels a bit mean-spirited to build a cult round his defects as an all-American leading man. (As well as a strong yet unplaceable accent – Czech with a heavy overlay of Alsatian French is the best-informed guess that’s been offered – he has haunted, suspicious eyes, a droopy eyelid, a pale, pitted face, a wild mane of dyed hair and disturbingly pumped-up middle-aged musculature.) A similar feeling applies in spades to Juliette Daniels, who squeezed herself into Lisa’s ill-chosen outfits before submitting to the artistry of Wiseau’s lighting department. The other alarm bell kicks in when you notice that, in addition to enacting a crazed dream of stardom, the film is essentially a self-pitying fantasy about friends and lovers and why one might not have them. It’s hard to imagine a directorial backstory that isn’t, at some level, desperately sad.

The Disaster Artist – a memoir by Greg Sestero, who played Mark, with upmarket writing assistance from Tom Bissell – makes it clear that such imaginings aren’t off target. Still, the book does an elegant job of having it both ways by projecting Wiseau as a divided soul, part loveable optimist, part manipulative creep. The second persona’s activities dispel any qualms we might have about laughing at the first’s, leaving just the right amount of poignancy for the writers’ occasional glimpses into an abyss of loneliness and need. Sestero knows both sides of Wiseau well because, before serving as a line producer and actor on The Room, he was his flatmate, having met him in an acting class in 1998. As the book skilfully tells it, Wiseau – who, then as now, was tight-lipped about his age, his place of birth and the sources of his apparent wealth – was alternately encouraging, controlling and emulative towards the young model-slash-actor. Sestero, in turn, drew strength from Wiseau’s delusional artistic self-confidence and didn’t mind being offered a room in LA on the cheap. Sestero’s triumphs, such as landing the lead role in a straight-to-video movie, provoked jealous outbursts. In the aftermath of one such episode, Wiseau started writing The Room.

Wiseau’s notion of what friends do was frozen forever, Sestero and Bissell suggest, when Sestero taught Wiseau how to throw an American football. One much-queried shot – a sudden zoom, accompanied by an eerie flourish on the soundtrack, revealing that Mark no longer has a beard – was, they believe, thrown in to licence Johnny’s use of Wiseau’s nickname for Sestero, ‘Babyface’. (Sestero, who’d grown a beard for the film in the hope of going unrecognised should it be released, was upset.) Wiseau’s habit of taping his personal calls was what made him think it a fine idea to have Johnny plug a cassette recorder into the landline after overhearing Lisa non-telephonically discussing her affair. When feeling blue, he’d bombard Sestero with answerphone messages: ‘I eat oranges in bed now. Feels so good. You should try it sometime with your French girl. Call me!’ His methods led to heavy turnover among the crew, who were perplexed by his inability to remember self-written lines – ‘It’s bullshit! I did not hit her! I did not! Oh, hi, Mark’ took 27 takes – and appalled by the pleasure he seemed to derive from performing in the finished cut’s 11 minutes’ worth of ‘love scenes’.

When The Room was eventually exhibited, Sestero’s mother remarked that 'to pay $6 million to make out with a girl was “pretty pathetic”.’ A rival actor turned to Sestero and said: ‘Oh, by the way – I checked online. This is going to be on your IMDb for the rest of your life.’ The writers don’t disclose the above-average sum that overcame Sestero’s reluctance to play Mark, but it can’t have been all that big, and his IMDb page hasn’t got notably lengthier. Still, he and Bissell have got a good book out of the experience (it's just been optioned by James Franco’s production company), and Sestero gamely shows up at selected screenings with Wiseau, who – so far as anyone can tell – quite enjoys his odd brand of fame. Fans, some of them sporting wigs or crudely-drawn droopy eyelids, get to throw a ball around with the film’s stars before trooping in to Rocky Horror-style festivals of audience participation. For $3.99, home viewers can buy an audio commentary from Rifftrax in which professional comedians aim zingers at the action onscreen. So if you’re not comfortable making your own jokes, or haven’t got anyone to share them with, you can download some voices to keep you company as you laugh at Wiseau and his imaginary friends.

Comments