On the Bus

Gillian Darley

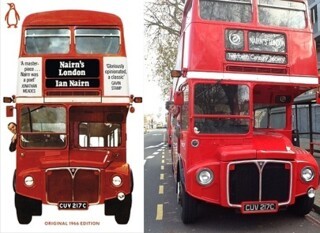

Nairn’s London has just been reissued by Penguin, with an afterword by Gavin Stamp. On Sunday, the Routemaster bus that appears on the cover of the 1966 edition (registration number CUV 217C; Ian Nairn leaning jauntily from the cab), took fifty of Nairn’s devotees on a tour of his London.

We met in the café next to Spiegelhalter's, a tiny, obstinate frontage to a former jeweller's shop on the Mile End Road. The proprietor had refused (c.1920) to give way to the mighty Wickhams (a department store with Selfridgian ambitions, at least in the architecture), ‘thereby putting their Baroque tower badly out of centre’, Nairn wrote, and offering a ‘perennial triumph for the little man’. Or not quite perennial. Now a shell, smothered in advertising material, Spiegelhalters is a token of the developmental wrestling matches taking place all over the East End – on the Bishopsgate Goods Yard, at Dalston, on the New Era estate in Hoxton.

Had the Wickhams spat been taking place in the 1960s, Nairn wrote, ‘smooth lawyers and architects could probably have presented a case for comprehensive redevelopment and persuaded the council to use their powers of compulsory purchase.’ Around Cable Street, the battle for Wellclose and Swedenborg Squares had been lost to well-meaning LCC ‘slum’ clearance.

In 1966, buildings nearer the City seemed threatened by commercial rather than social pressures. The 1868 Hill & Evans vinegar warehouse on Eastcheap was an example of polychromatic Gothic Revival architecture so wild it seemed to be ‘the scream that you wake on at the end of a nightmare’. The building is still there, loomed over by the monstrous ‘Walkie Talkie’ office block, a top heavy beast that impedes every view into the City (and in the summer of 2013 turned into a burning mirror).

Leadenhall Market in the 1960s was overwhelmed by the heft of the City and vulnerable to demolition; it’s now listed. The ‘Cheesegrater’ soars overhead, but at least it bows to perspective and narrows towards its apex.

Nairn found Christ Church Spitalfields ‘locked up whilst money is being raised for a restoration’; we found it open but full of cheap chairs and jangly music. Bevis Marks Synagogue (its furnishings intact) was the creation of a Quaker builder, following the lines of the immense Sephardic synagogue in Amsterdam, conveying the message, Nairn said, ‘that the real parts of all religions are identical’.

Reaching Somers Town by dusk, the Routemaster left us at the Cock Tavern, an unimproved, independent Irish pub. It, too, finds itself menaced by the march of gentrification, threatened by work at Euston and for HS2. Pubs were Nairn’s passion, and his undoing: he died, poisoned by alcohol and depression, in 1983, aged 52. Most passengers on the Routemaster were too young to remember Nairn’s journalism, books or TV films during his lifetime, but they are from a campaigning generation, and recognise him as both poet and prophet.

'Ian Nairn: Words in Place' by Gillian Darley and David McKie is published by Five Leaves Press.

Comments

When I first came to London in 1976 it was a dump, now it's becomng a bit dull. Even here in Camberwell the nooks and crannies, the crooks and grannies, are disappearing. However, I must remember I live in one of the little villas that progressed up the hill to the dismay of the people with taste on Georgian Camberwell Grove.

Nairn is right about character, modernisers are right about space. But today, the values of modernisers are - and my knib splits as I write it - shareholder value, which disperses worldwide, leaving a layer of idiotisation, like demolition dust, that just won't go away.