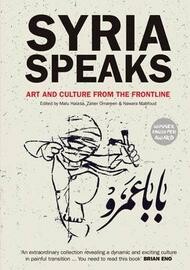

‘Syria Speaks’

Ursula Lindsey

A few days before Isis fighters captured the Iraqi city of Mosul, Saqi Books released an anthology called Syria Speaks: Art and Culture from the Frontline, a thoughtful collection of work by Syrian writers, activists, visual artists and anonymous collectives who were at the vanguard of the uprising against Bashar al-Assad in March 2011.

Much of the work in Syria Speaks seems to have been written a year or two ago, and what a difference that time makes. Most of the more than fifty contributors are outside Syria now; their hope and defiance seem out of date. Yet the book is a valuable reminder that the early protests against Assad were both peaceful and democratic. It also sheds light on the way the protesters’ aspirations were ground into irrelevance.

In the opening piece, the journalist Samar Yazbek travels though the countryside around Aleppo, Idlib and Hama:

The sun was blazing down, so intense that it was impossible to cry. Everyone spoke with granite-like solemnity; a brief sigh was enough to occupy the whole space… It was as though we had uncovered Syria’s true identity after all this time: a country made of earth, blood and fire, where explosions never ceased.

The Assad regime did its best to militarise the conflict as quickly as possible. According to several testimonies in Syria Speaks, soldiers used rape to punish dissident villages and provoke further violence; activists and protesters were arrested, tortured and disappeared.

The spectre of prison hangs over everything, as Zaher Omareen, one of the book’s editors, points out. He describes staying in a hotel owned by the military: ‘What is unbearable is the presence of a photograph of the Eternal Leader above the bed in all the rooms. It is not even possible to dream without the regime’s surveillance.’ But ‘there is no need for pictures in prison. Everything attests to the state’s absolute dominance… On the outside, the ubiquitous photograph of the Syrian leader has a purpose. It is there to make you think of one place, always: prison.’

Dara Abdullah writes of his own detention. A fighter from the Free Syrian Army was dumped in his cell to die slowly of septic shock. The smell of his wounded leg was so disgusting the other inmates eventually lost all sympathy for him. Fadia Lakzani describes her efforts to locate her brother, arrested in the 1980s; after many years she finally came to believe he had been killed. Even the sectarianism that has overtaken the conflict in Syrian is compared to a jail. ‘The religious collective then becomes a prison,’ Hassan Abbas writes, ‘the inmates of which can only see the world through a narrow window.’

The book includes work by visual artists such as Sulafa Hijazi and the cartoonist Ali Ferzat, and also covers photography, cell phone footage, posters calling people to protest, graffiti and finger puppets. The artists and writers interviewed are articulate about the way they have been sidelined. ‘People in the West are no longer listening to Syria,’ says Asaad al-Achi, a former member of the Syria National Council and an organiser of medical relief. ‘By the time the revolution had become fully militarised, decisions about its course were transferred to the world stage and became a power game between the camp supporting Assad and the camp supporting the revolution.’

But the voices in Syria Speaks cut through propaganda. The book provides a way of listening to and looking at the conflict when the horror of it makes many of us avert our gaze. ‘And what if you weep alone at the end of the night,’ the poet Ali Safar writes, ‘will the children find their way home in the morning, laughing, abundant as the rain?’