Types of Ambiguity

Juliet Jacques

Alice Austen’s photograph of herself and two other women dressed as men was taken in New York in 1891, anticipating the female masculinity of Radclyffe Hall and others. It’s one of the more than 200 images in Phaidon’s Art and Queer Culture, edited by Catherine Lord and Richard Meyer, which charts the shift from the ‘homosexual’ identities formulated by 19th-century sexologists and lawmakers to the fluid conceptions of gender and sexuality that characterise contemporary queer culture.

The first section, covering the years from 1885, when the law against ‘gross indecency’ was passed in Britain, to 1909, when Magnus Hirschfeld distinguished between homosexuality and transvestism, is full of portraits, like Austen’s, that can be read as queer, but were ambiguous enough to make it past the censor. The ambiguity, and the censorship, haven’t gone away. The Alice Austen House, Meyer says, has made it clear that researchers linking Austen to lesbian history are not welcome.

The precariousness of queer archives and the defiance of queer people in the face of denial or violence is a recurring theme in Lord and Meyer’s book, from the Nazi sacking of Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science in 1933 to the vandalising of LGBT, Aids and women’s health books in the San Francisco Public Library in 2001. Amy Conger made Queer Reader Mandorla by dyeing the slashed pages of A Queer Reader in high-contrast shades and pasting them into a collage around the cover image of a sailor in lipstick.

In the earlier parts of Art and Queer Culture, queer people are often subjects for investigation by straight photographers and writers. Lord and Meyer include one of Brassaï’s famous shots of sexual dissidents at Le Monocle, and a conversation between André Breton, Benjamin Péret, Jacques Prévert, Raymond Queneau and others in January 1927, which reflects the Surrealists’ anthropological view of homosexuality. Queneau and Prévert expressed their disdain for the 'extraordinary prejudice against homosexuality' within the movement; Breton was vehemently homophobic but awkwardly tolerated Claude Cahun, one of whose Cancelled Confessions closes the second section, ‘Stepping Out 1910-29’.

In his introductory essay, ‘Inverted Histories: 1885-1979’, Meyer quotes Nayland Blake’s assertion that ‘the discourse of the postmodern is the queer experience rewritten to describe the experience of the whole world,’ as Susan Sontag’s Notes On Camp questioned the categories of ‘man’ and ‘woman’ and associated behaviours, as well as the boundaries between ‘high’ art and the ‘low’ culture in which queer people often had to express their desires.

In 1965, hand-drawn symbols started to appear beside the photographs in Physique Pictorial, published by the Athletic Model Guild. Subscribers who wanted to know what the symbols meant could send off for a copy of the so-called Subjective Character Analysis chart; experienced readers would know what ‘late riser’ and ‘very affable’ really meant.

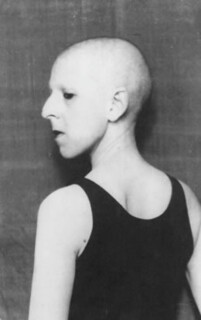

The increasing confidence after the Stonewall riots in 1969 created tension between gay, lesbian and bisexual activists, as gay power and the Gay Liberation Front led the fight for ‘homosexual rights’. (Their difficult relationships with gender-variant activists receive less attention in Art and Queer Culture, perhaps because they were played out in theoretical texts more than art.) But it also gave rise to a sense of a strong cultural heritage, and of the underlying queerness of modernism, evident in Ulrike Ottinger’s film Freak Orlando.

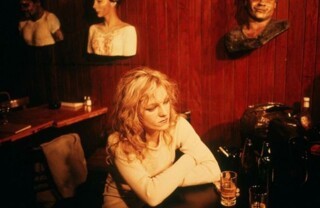

One of the last images in Art and Queer Culture is a portrait by Nan Goldin of the actress and writer Cookie Mueller. Taken in 1983, it was one of the 15 photographs that Goldin collected in The Cookie Portfolio 1976-89 after Mueller’s death from Aids six years later. Lord and Meyer’s caption describes Goldin’s regret that ‘photographing couldn’t keep people alive’. No image in the book captures the long, constantly shifting balance between defiance and sadness that characterises queer history quite as much as this one.