Ersatz Asterix

Thomas Jones

The 24th and last canonical Asterix book – which is to say, the last one written by René Goscinny and drawn by Albert Uderzo – was Asterix in Belgium (1979). Goscinny died in 1977, soon after he'd finished writing it, and the publishers had to take Uderzo to court to get him to do the pictures. Belgium completed the list of France’s immediate neighbours visited by the indomitable Gauls: they went to Germany in 1963, Italy in 1964 (and several times since), Britain in 1966, Spain in 1969 and Switzerland in 1970. They also went to Egypt to help build a palace for Cleopatra in 1965, Tunisia with Caesar’s Foreign Legion in 1967, Greece for the Olympic Games in 1968, Corsica in 1973, and North America and Scandinavia in 1975, as well as having several adventures at home in between.

Uderzo carried on more or less reluctantly by himself for 25 years after Goscinny's death, producing eight more albums of steadily deteriorating quality. But he has now definitely retired (he’s 86) and the latest Asterix book, in which the Gauls go to Scotland, has been written by Jean-Yves Ferri and illustrated by Didier Conrad, with Uderzo looking over his shoulder.

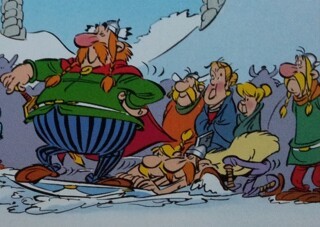

The best that can be said about Asterix and the Picts is that there's a nice visual joke towards the beginning, with Chief Vitalstatistix riding his shield like a sledge, and the book is better than half of Uderzo’s solo stuff, though that isn't saying much. Ferri and Conrad's work is by definition derivative, and the skeleton of the plot bears a more than passing resemblance to Asterix in Corsica – an inscrutable warrior from a distant land turns up in the Gauls’ village; Asterix and Obelix escort him home where he unites his countrymen and they throw out the Romans – but that just goes to show that plot isn't everything.

Ferri and Conrad have said that ‘the only place where Asterix can't mean anything is the US, which is the only great empire left today, because they can only relate to the Romans and not the small village.’ Overinsisting on the parallels between Rome and the US is unhappily reductive (though there’s quite a funny moment in Asterix and the Picts when one legionary says to another: ‘“Logistical support" my eye!’). Mary Beard, reviewing Asterix and the Actress in the LRB ten years ago, acknowledged the temptation to read ‘the cartoon conflicts between nice Gauls and nasty Romans as a thinly veiled attack on American imperialism and the dominance of the new superpower’, but suggested that the main reason ‘the United States is the only country in the West where Asterix has remained a minority taste’ is that ‘Asterix is indomitably European. The legacy of the Roman Empire provides a context within popular culture for the different countries of Europe to talk with, and about, each other, and about their shared history and myths.’

Some of that shared history was less than twenty years past when Asterix the Gaul came out in 1961. As Nicholas Lezard spelled out in a letter responding to Beard’s piece, ‘the Asterix series is as much about the German occupation of France (and other countries) during the Second World War as it is about the Roman occupation,’ though ‘the allegory isn’t rammed home’ – and in fact Beard had more than gestured towards it with her observation that the ancient Gaulish leader Vercingetorix ‘did double duty’ for the French ‘as “the first resistance fighter in our history” and as a symbol for Pétain and the Vichy Government’. It’s no coincidence that the shame of Caesar’s defeat of Vercingetorix at Alesia is felt most strongly by the Gauls that Asterix and Obelix meet in The Chieftain’s Shield, when they accompany chief Vitalstatistix to Aquae Calidae, i.e. Vichy, for a spa treatment.

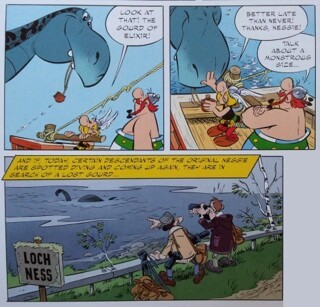

There's a running gag in The Chieftain’s Shield that ‘no one even knows where Alesia is.’ This is now true, though it wouldn’t have been in 50 BC. As in The Flintstones, a lot of the jokes in Asterix rely on anachronisms. In Asterix in Britain there are ox-drawn double-decker buses, pubs with dartboards, the Beatles (‘a very popular group, they're top of the bardic charts’) and a rugby game. In Asterix and the Picts there’s a goofy Loch Ness monster (which makes far too many appearances), whisky, ‘a Loch Androll tune played by our bards’ and caber-tossing.

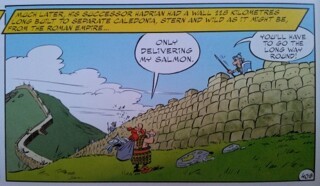

An Asterix adventure in Scotland wouldn't be complete without a reference to Hadrian’s Wall, but rather than working it into the story (in Asterix and Cleopatra, Obelix climbs on the Sphinx and knocks its nose off) or making it a throwaway joke (crossing the Thames in Asterix in Britain, Obelix says: ‘I think this bridge is falling down’), Ferri and Conrad just give the wall an extraneous panel to itself a few pages from the end, like a tired afterthought.