In the Reading Room

Gillian Darley

In 1857 Prosper Mérimée went to London to see Anthony Panizzi’s new Reading Room at the British Museum. As the head of the commission charged with transforming the Parisian national library, Mérimée was hugely impressed by what he saw: the top lighting, the drum-form and the integrated, orderly systems, all designed for a general reading public, not just a few clerics, rulers and their acolytes, the previous users of the great libraries of Europe.

After reading Mérimée’s ecstatic review, Henri Labrouste hurried to London. A few years earlier, Labrouste had completed the soaring new reading room of the ancient Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève in Paris, a mesmerising space forested with iron columns and glowing by gaslight after dark: for the first time, reading hours extended into the evenings. Now he was commissioned to reconstruct the Bibliothèque impériale (soon to be nationale). It took him fifteen years.

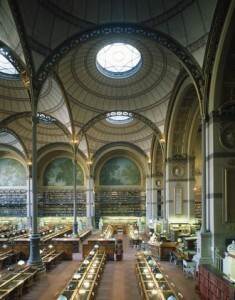

Readers enter Labrouste’s Bibliothèque nationale through a bosky vestibule, jostling with busts of great authors and frescoed with trees: he couldn’t persuade the authorities to plant a modest urban forest (as now stands at the core of Dominique Perrault’s national library on the Seine). The immense reading room has almost byzantine splendour, its nine domed spaces demarcated by spindly trunks of etiolated ironwork. (Labrouste’s inspiration for using so much exposed structural ironwork indoors came from early 19th-century Parisian market buildings and railway stations.) Beyond, behind a massive glass screen, the bookstacks stand on functionalist metal grilles, allowing natural light to percolate down through five floors. Nineteenth-century library users, their feet toasty from Labrouste’s novel heating arrangements, waited for their books to hurtle their way along pneumatic tubes. Labrouste was both a relentless innovator and a convinced romantic, a social visionary and an architectural magician.

Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light is at MoMA until 24 June. From Manhattan, the exhibition took me back to Panizzi’s public library in London. It’s currently used for temporary exhibitions, with mixed results; the Pompeian atrium inserted into the drum disrupts the geometry. But the British Museum’s new wing promises a dedicated exhibition gallery, and consultations are due over the future of the Reading Room. A great interior is sitting there, masked by blackout screens and false floors. It deserves a touch of magic again, beginning with books.

Comments

the overlapping domes of the BN are more about communication than contemplation.