At Tate Britain

Alice Spawls

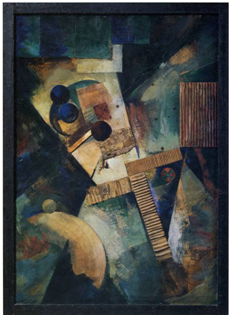

Kurt Schwitters was 53 when he arrived in Britain in 1940. The Nazis had labeled him an ‘Entarteter Künstler’ (degenerate artist); in Britain he was an enemy alien, locked up in Hutchinson Internment Camp on the Isle of Man: brown walls, grey tiles, grey Irish Sea. The first room of Schwitters in Britain (at Tate Britain until 12 May) gives a glimpse of his life before exile. Schwitters hovered butterfly-like on the fringes of the major European isms of the 1920s: a bit of Dada here, a bit of De Stijl there. The geometry of Ja-was? Bild, with its strips of corrugated cardboard like sign posts in a blast of blue-green abstraction, makes dramatic use of a Suprematist grammar.

Schwitters came up with the word 'Merz' to describe the style of his abstract collages: it 'originated from the Merzbild,' he said, 'a picture in which the word MERZ, cut out and glued on from an advertisement for the KOMMERZ-UND PRIVATBANK could be read between abstract forms,' and involved 'the combination of all conceivable materials for artistic purposes and technically the principle of equal evaluation of the individual materials... a perambulator wheel, wire-netting, string... having equal rights with paint.'

He was famous too for his sound poems: a recording of 'Ursonate' echoes through the gallery (the Daily Mail mocked it in 1936 and the BBC gave up trying to record it). 'An Anna Blume' ('To Eve Blossom') is often called a ‘Dada love poem’ although the Dadaists put out an official statement denying it. It begins, in Schwitters’s translation:

Oh thou, beloved of my twenty-seven senses, I love thine! Thou thee

thee thine, I thine,

thou mine, we?

And goes on:

Eve Blossom, red Eve Blossom what do people say?

PRIZE QUESTION: 1. Eve Blossom is red,

2. Eve Blossom has wheels

3. what colour are the wheels?

‘I prefer nonsense’ he wrote, ‘but that is a purely personal matter.’

In Britain, nonsense wasn't the order of the day and Merz became an artistic survival technique. At Hutchinson camp supplies were scarce, but art flourished: inmates mixed brick dust with sardine oil for paint, tore up the lino floors for print-making and engraved images on the blue-tinted windows. Schwitters made porridge sculptures, which developed a 'musty, sour, indescribable stink' and 'greenish hair'. Once released he moved to London, painting portraits for cash – the figures and landscapes are one of revelations of the show – and documenting war and exile in collage. Untitled (This is to certify that) includes a Royal Institute of Public Health seal, bus tickets and Liquorice Allsorts packets, but under these pieces of his British life (and upside down) are scraps of Dutch: the word BEWAREN stands out and large black shapes dominate the page.

After the war ended he moved to the Lake District and began to build the Merzbarn, a rural version of the angular architectural Merzbau that had taken over half of his family’s Hanoverian home. Leaving behind urban materials he impressed twigs and stones into the plaster wall. The one section that was complete when he died (and is now in Newcastle’s Hatton Gallery) shows the transformation of Merz from Bau to Barn: the austere, discordant forms were softened into a murky pastoral; more lyrical and less sure of itself.

The final rooms are taken up with the work of two young artists, Adam Chodzko and Laure Prouvost (shortlisted for this year's Turner Prize), whom the Tate commissioned to respond to Schwitters's work in Britain. Prouvost's short film is marvellous: she narrates the (fictional) story of her grandfather, imagined to be a friend of Schwitters, while walking around his house, which is like a fully realised but dilapidated Merzbarn. The interior of the house is covered in mud – her grandfather, she says, dug his way out and eventually disappeared – and the film slices continually with shots (and sounds) of tea being made and poured: Schwitters gave the nickname 'Wantee' to Edith Thomas, his companion in England, because she was always interrupting him with offers of tea. Throughout the house are artworks that Prouvost says her resourceful grandmother reclaimed for practical ends: sculptures made into doorstops, coat-hooks, shovels for the mud. With the story of her grandfather's gradual isolation from the art world and disappearance, Prouvost gently satirises the British critical bafflement at, and then exclusion of, Schwitters's late work: 'Useful as a tray, but as a painting... what do you do with it?'