In Kirov Forest

Peter Pomerantsev

There was much talk of fairy tales in the court-room in Kirov where Alexei Navalny gave his closing statements on Friday. Since leading the failed revolt against Putin’s kingdom of corruption, Navalny has been charged with stealing 16 million rubles worth of Kirov Forest when he was assistant to the local governor in 2009. No evidence against Navalny was presented during the trial. No profit was made from the alleged illegal transaction. The case for the prosecution was based on allegations from a local magnate Navalny had attacked for insider dealing. The state prosecutor has recommended Navalny spend six years in jail (just enough to keep him locked up until after the next presidential election).

‘There must be some limits to this absurdity,’ Navalny said. One of his supporters read Kafka’s Trial. ‘This case is only happening so everyone in the country knows me as the guy who stole the forest,’ insisted Navalny. ‘Let us get out of the world of fantasy and fairy tales. I will not stop fighting the disgusting feudal system which sits like a spider in the Kremlin, the 100 families who are sucking the blood out of Russia.’

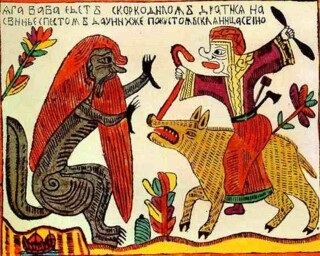

The heroes and heroines of Russian fairy tales often have to go into the ‘dense, dark’ forest, to steal a magic implement, or chop down trees, and find themselves sucked into a strange world where nothing is as it seems, at the mercy of shape-shifting wood-sprites, Baba Yaga with her house on chicken legs surrounded by glowing skulls, Koschei the Deathless who sucks the life out young women and can only be destroyed if you can find his soul, which is hidden in a needle, which is in an egg, which is in a duck, which is in a hare, which is in an iron chest buried under a green oak tree on the island of Buyan.

Phantasmagoria is the dominant mode of Putin’s latest presidency, as the screws are tightened and the purges begin. The Duma, for so long cultivated to give at least the impression of debate, has exploded in a shrill cabaret of obsequiousness. A stream of patriotic laws are being passed, forbidding, inter alia, English words, adoption by Americans, gay ‘propaganda’. Cossacks in full traditional garb patrol the streets of Moscow to check the papers of anyone who doesn’t look Russian; religious nationalist Hells Angels ride through cities waving flags of Christ, calling for the defence of Holy Rus from western infidels and blaring mystic heavy metal tunes called things like ‘Slavic Skies’. In Rostov, a member of the Eurasian Youth Union, Alexander Proselkov, dressed up as an NKVD officer from the 1930s, shot a toy pistol at balloons with liberals’ names on them (including Navalny and Gorbachev). ‘We’re too tolerant of the liberal opposition,’ Proselkov said. ‘We need to bring back the spirit of 1937.’ As Kremlin media turn up the rhetoric about homosexuals being a fifth column of western influence, patriotic teenagers have been arranging fake dates with gay teenagers online: when the victim turns up, he is met by a gang who taunt him, film it and put it on YouTube.

It’s difficult to tell how deep the new ideology goes: polls seem to show that most Russians are largely indifferent to religion, or Cossacks, or homosexuality. But the Kremlin has ways of dealing with polls that aren’t to its liking. After the Levada Center, Russia’s most respected polling institute, published polls that showed Putin’s popularity was waning, the Kremlin accused it of being a ‘foreign agent’. It may be closed down.

Meanwhile the Kremlin has been whispering disorienting rumours: the protest movement, the new story goes, was provoked by Kremlin hardliners to create an enemy they could then use as an excuse to start a new wave of repression. Who would try to fight with that thought planted in their heads? ‘I can’t tell what the genre is any more,’ Navalny said in his closing statements, ‘comedy or drama.’

At the end of a fairy tale the hero leaves the forest to return to reality. Arrest, exile, prison have taken on a ritual meaning in the new Russia. The ride in the police van after a protest is like the journey out of the matrix. I remember the first time I visited the offices of Novaya Gazeta in Moscow. The meeting room had the look of a shrine: there were photos of killed journalists with black ribbons on them. The reporters I met at the newspaper were literally prepared to sacrifice themselves for the truth. For someone raised in the tepid waters of Western Europe it all seemed somewhat intense. It took me several years living in Russia to realise that’s how hard you have to scream to wake yourself up.

Comments