At the Estorick Collection

Alice Spawls · Morandi

Small pictures, especially works on paper, sit more comfortably in the intimate proportions of a house than in a lofty gallery hangar, and the exhibition of watercolours and etchings by Giorgio Morandi at the Estorick Collection (until 7 April) is a well-turned example of what can be done with such an arrangement: the pictures are allowed to speak for themselves.

There are more than 80 etchings, which span the artist’s lifetime (it seems wrong to say ‘career’: he lived and worked very quietly in Bologna, the city where he was born, and was known as 'the monk'). Together they form a surprising counterpart to his better-known paintings. Unlike those sombre still lifes, his etchings are lively and experimental, and include a number of landscapes of the countryside around Grizzana, where he went every summer, as well as the familiar compositions of bottles and jugs.

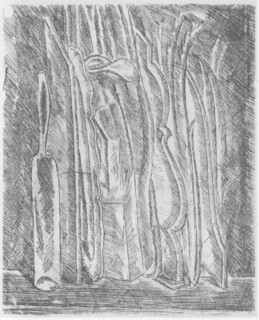

In the early works the dominant Cubist/Futurist influence can be seen: the elongated forms that fill the page in Still Life with Bottles and Pitcher (1915) jostle for space; the marks are noisy scratches on the smooth surface of the etching plate.

A more subtle relationship between objects quickly developed, however. In Still Life with Bread and Lemon (1921), a slightly fuzzy lemon points towards the open face of a sliced chunk of bread, their tentative conversation thrown into relief by the dark circles of shadow from which their forms emerge.

Peter Campbell said that Morandi 'swaps representational information for painterly texture’, and it is true of his prints too. He hatches and cross-hatches with hard clean lines to create areas of texture and tone that relate to each other spatially. Wet slicks of blank white paper drip down the sides of two large jugs in Still Life with Five Objects (1956, top). The dense V between them is a forest of knitted lines. They face away from the viewer towards the dark shape of a vase.

Unmarked paper is used to striking effect. In Savena Landscape (1930) a molten white river flows between banks of gradated lines. The foreground foliage is not outlined: its loosely woven mesh of hatched lines is frayed at the edges. The haze of marks allows the white of the paper to shine. Against a background of shadow Still Life of Vases on a Table (1931) has silhouettes of light: the unetched forms of slender-necked bottles blaze against the sturdy dark shapes behind.

Across the surface of his etchings Morandi traces the relationships between objects and the space around them. Unable to develop these nuances tonally as in his paintings, he experimented with shading and mark-making, replacing colour with texture. The empty space is not left blank but worked as a subject: sometimes with long, dark marks, sometimes with close cross-hatching or neat pale dashes. Setting up these tabletop appositions was almost as arduous as depicting them:

It takes me weeks to make up my mind which group of bottles will go well with a particular tablecloth. Then weeks thinking about the bottles themselves, and yet often, I still go wrong with the spaces. Perhaps I work too fast.

The bushes and trees of Grizzana Landscape (1932) appear in a camouflage-like pattern of lighter and darker patches. The brisk strokes have an energy we’re unaccustomed to encountering in Morandi’s work. He uses a similar technique in Le Lame (1931), where the nearest trees are etched in undulating rows of short, light marks which weave into each other. Held up by dark branches they seem almost to shimmer.

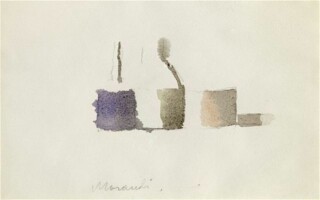

The watercolours, from the last years of his life, are a further revelation. Instead of sharp lines there are gentle diffusions of colour: the ghost of a pencil mark is the outline of a bottle, indigo bleeds faintly into black, peach into grey. They convey the merest touch of information: the spout of a jug, a bottleneck, a cylinder. The relationship between space and object is the guise in which a more intriguing drama emerges: that of paper and paint.