At the Grand Palais

Joanna Walsh

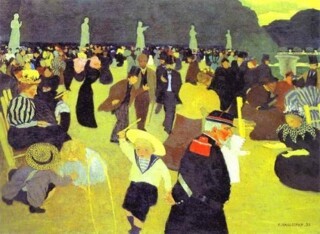

There are great tracts of space in Félix Vallotton’s paintings; they are not quite flat, but are built up from tiny feathered strokes in shades of the same colour: arsenic green walls and sofas like medicine phials in a chemist’s window. These strokes don’t add much contouring or depth; what concerns Vallotton is the space. He draws our eye to the floor, the walls. In his early paintings of the 1890s and his famous woodcuts for La Revue blanche, people form patterns or highlights. The choleric old soldier in Jardin du Luxembourg (1895) – a veteran of the Franco-Prussian campaign – is a hate-figure picked out again and again in Vallotton’s satirical woodcuts (in La Charge a platoon of elderly soldiers ‘disperse’ a civilian protest).

Around forty prints and sixty paintings at the Grand Palais form the first retrospective of Vallotton’s work in nearly fifty years. They are organised thematically rather than by period (‘Idealism and the Purity of Line’, ‘Icy Eroticism’, ‘Repression and Lies’) and you can see how the artist returned to subjects and techniques: sunsets, street life, nudes, classical allegories, war and, above all, interiors.

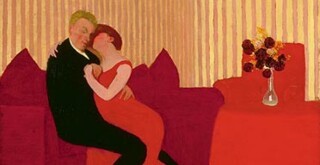

Vallotton’s interiors are uneasy: people are always leaving or arriving; interactions – part public, part private – take place in doorways. All kisses are illicit. People become objects: partly in shadow, the light flattens rather than moulds them. In The Lie (1898), a woman in scarlet is the ‘s’ of her dress, her head tipped back so that her features disappear entirely. The subject of La Chaste Suzanne (1922), as much as the disparity between the title and the picture’s heroine, is the light that bounces off her suitors’ bald heads and the sequins on her hat. La Loge de théâtre (1909) recalls Goya in its intense yellow and the (un)importance Vallotton accords the two minuscule smudgy faces in the centre.

If Vallotton is Goya’s grandson, he’s close to being Hopper’s uncle. Like Hopper, he’s a painter of, and by, artificial light. Vallotton’s gaslight comes from unseen windows and invisible lamps. Interactions are just as indirect. No one looks at each other: the man frowning into his absinthe looks away from his companion, whose face is shaded by a fashionable hat. Vallotton’s street scenes are strikingly cropped. A man’s legs disappear into the top corner; a woman’s hat bobs towards us but we see only its flowers and feathers: her face is cut off by the frame. Vallotton’s pictures suggest photographs, or movie stills.

Around the turn of the century Vallotton began drawing from photographs he took himself, some of which are shown alongside the paintings. These photographes ratées (‘spoiled’ but also ‘missed’) are the opposite of Cartier-Bresson’s ‘decisive moment’. Vallotton’s are more like holiday snaps in which a thumb blocks the top of the Eiffel Tower, or someone’s head is split in half by a low hanging branch – and he reproduced the effect in his paintings. Scenes don’t portray ‘events’ but a series of disconnected coincidences. In decorative interiors and lush landscapes, couples look to each other and find nothing.

Comments

Marvellous stuff.

A distinct contribution - the palette, the flatness, from extravagant colour (Evening on the Loire) to impressionistic 'tonalism' (Neva, light fog), and the implicit social commentary on those formal bourgeois interiors.

Why has this painter's light been under a bushel for so long?