Ellen Gallagher: AxME

Nick Richardson

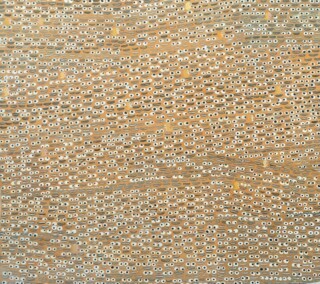

How we look, and transform how we look, has been Ellen Gallagher’s preoccupation for the last twenty years. Throughout AxME, Tate Modern’s stunning retrospective, images of our mutable features – lips and eyes especially – recur with a frequency that suggests fevered obsession. A large, early painting, Oh! Susanna (1993), looks from a distance like an Agnes Martin abstract weave of dots and lines on a smudgy orange background, but is actually composed of tiny lips and eyeballs and the odd, disembodied Barbie’s head. Portraits are closer to abstract works than we imagine, Gallagher seems to be saying: eyes give faces character, but abstracted from context they are blobs of colour, windows onto a soul that refuses to materialise.

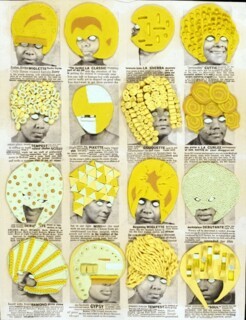

The painting takes its title from one of the best-known minstrel songs of the 19th century, and the lips and eyes that constitute it represent, in Gallagher’s words, ‘the ephemera of minstrelsy’. As the daughter of a black father of Cape Verdean extraction and a white Irish Catholic mother, Gallagher is particularly interested in the variations of lips, eyes and skin colour that transform a black face into a white face and white into black. Room 2 at Tate Modern’s show is dominated by Pomp-Bang (2003) and Double Natural (2002), two massive canvases, 2.5 by 5 metres, covered with adverts cut out of newspapers for face-transforming products including Kongolene, a pomade for smoothing afros, and various skin-lightening creams. Stuck to the faces of the ads’ models are exotic wigs moulded in yellow (half brown, half white) plasticine.

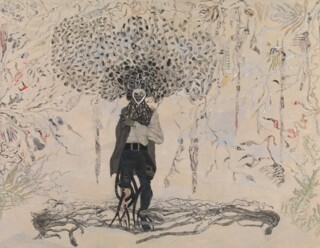

Some of the hairpieces are intricately pock-marked to look like coral, others resemble beehives, or bunches of bananas. Black faces are transformed into exotic alien lifeforms. Gallagher seems to be lampooning one kind of facial transformation while making another attractive: why go from black to white, when you could go from black to gloriously coiffed cyborg? Faces are artworks: express yourself! It’s not surprising to find that Gallagher has titled a work Drexciya (1997), after the afrofuturist Detroit techno duo (recently celebrated by the Otolith Group) who reimagined Atlantis as a community of amphibious black warriors born from pregnant women who had been thrown off slave ships. In her take on the myth, Gallagher has laid out a grid of women’s heads, and given them ice cream-white afros and eyes that ooze pink goop. The pirate portrayed in Bird in Hand (2006), in oil, pen and cut-out pieces of paper, is a better icon of transhumanism. His peg leg has sprouted black tendrils, and jellyfish swarm round his hair; the lace of his cuff is as intricately patterned as the coral that surrounds him. For Gallagher’s Drexciyans, marine lifeforms are style advisers.

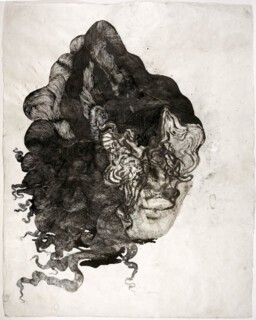

For the ‘Black Paintings’ of the late 1990s, Gallagher made whole canvases wear blackface. Complex collages of faces, weaves and geometrical shapes were painted over in black paint, then scrawled on in spidery white. They offer, perhaps, a metaphor for the way that the reductions of racial thinking have buried black art. But they are also effective abstract works in their own right: post-Rauschenbergian reflections on the play of light and texture on the canvas surface. They are, Gallagher has said, ‘a kind of refusal. If you stand in front of them they go blank and then if you stand at the side you see only a little.’ Her interest in the manipulation of light and surface is again on show in the Morphia (2008-12) series of double-sided drawings/collages on tracing paper, in which faces, or almost-faces, are haunted by the designs behind them. A black bolus of matted hair is given aqueous fluidity by the blue watercolour and (lip-like) glue swirls behind it. In another, hair, and an eye cut out of a magazine, are completed by the red-pink patch on the verso that suggests a pair of lips. One identity half-conceals and is half-shaped by another, just as the face we’ve been given and the face we desire make a third face: our own.