Incite!

Stephanie Burt

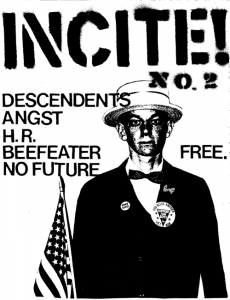

Timothy Alborn is the dean of arts and humanities and a professor of history at Lehman College of the City University of New York, and a scholar of Victorian business history. From 1989 to 1998 he ran Harriet Records, which released singles and CDs by never or not-yet famous pop groups such as the Scarlet Drops, Twig and Wimp Factor XIV. From 1985 to 1998 he also published Incite!, a fanzine with perhaps as many as several hundred readers, fans of obscure pop and rock bands from Boston to Dusseldorf to Melbourne. (During the 1990s Alborn taught at Harvard, where I met him and became a fan of his work.)

For more than a decade you could read Incite! only if you got it from Alborn, or if you got it from someone who got it from someone who got it from him. No more: all thirty issues are now online, thanks to Lehman College, and they confirm, or reveal, Alborn’s strengths as a whimsical, deliberately unambitious, yet serious writer. They also confirm the strengths and the contradictions in fanzine culture, in the unassuming network of writers and readers and listeners from the years before the internet, who had to share their tastes and obsessions through the mail.

Alborn’s writing at its finest is short-form, impressionistic, non-technical criticism at its finest, with jokes. Pittsburgh singer Karl Hendricks sounded better solo than with his first rock band because ‘Like some other people I know, he’s much easier to take when he’s in a room by himself than when he’s surrounded by friends.’ Incite! #3 (1987), written just after Alborn finished his first year of graduate school at Harvard, recommends

listening to ‘All Hung Up on What Used to Be’ by the Flies and pretending it doesn’t apply to you… hiding from your friends by working with your enemies, overworking until you’re not sure anymore which ones are which, and avoiding the stench of it all by putting the needle down.

As Incite! went on it became less slapdash and more intricate, closer in look and spirit (though not very close) to illustrated Victorian miscellanies. Most things that Alborn reviewed were related to music – singles, albums, live performances – but he also examined the Slinky toy, the semi-academic British magazine Anarchy, dugongs and United Airlines.

Fanzines were a kind of reviewing, but they were also letters to strangers, distinguished by informality and sincerity, by enthusiasm and relative brevity, and by the anti-elite attitude of punk rock, even when the individual zine writers favoured far softer sounds. Sometimes strangers wrote back, and sent their own zines, or became contributors to Alborn’s. Incite! #27 (1994) took as its theme ‘epistolarianism’, life led through the post:

One of the perks of my job is that I get money to travel to distant libraries and read other people’s mail from one or two centuries ago… People should read these and remember why letters are better than phone calls or fanzines or just about anything else.

You can put together a superb listening list from the music that Incite!recommends, though some records, or tape cassettes, will be hard to obtain. Dumb macho punk mattered to Alborn when he thought it sounded good enough, but so did the overtly feminist thinking, and the melismatic oddity, of the Vancouver duo Mecca Normal, whose music Harriet Records later released.

You can also put together a reading list: upbeat, kid-friendly and anglophile, in a way only possible for Americans. There’s Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy (where the record label got its name), Stevie Smith (‘her novels as well as her poetry’) and Kenneth Grahame. There are also other zines: Hip Clown Rag, Cubist Pop Manifesto.

As Harriet Records grew, the zine began to promote the bands on the label. Incite! #24 (1993) introduced Harriets throughout history, among them the once notorious Harriette Wilson. Incite! #20 described a new Harriet single:

Magnetic Fields is actually this guy from Boston named Stephin Merritt who writes songs, plays a number of instruments and manipulates computer things.

On 25 April 2012, the Magnetic Fields headlined the Royal Festival Hall.

But most of the bands on Harriet never got nearly that big: they weren’t expected to. Nor could Incite! try to speak to a crowd. There’s a great paradox in Alborn’s critical project, one not restricted to pop music, and one that Alborn faced with exceptional honesty. Some works of art affect you as much for who you are as for what they are, and shouldn’t you say so if you write about them? Alborn complained in Incite! #15 (1989) about treating any song you like as ‘destined to go down in history as MEANING SOMETHING… when I thought that it meant absolutely nothing and that’s why it was so great.’

Incite! insisted that some things are better when they stay amateur, clearly personal and – not coincidentally – free. The zine’s attitude towards music thus met up with Alborn’s left-wing politics, and with the scholarship he would pursue: the last Harriet release, Friendly Society, took its name from the Victorian mutual-aid groups that for-profit insurance wiped out. Incite!, and Harriet, were also overtly feminist, without imagining that the guy who ran them could speak for women and girls. Instead he spoke for himself, against the masculinist and nihilist rockers who ‘write me off for having something to believe in’.

Oscar Wilde said criticism was autobiography in disguise; he was wrong in general, but he was right about zines. The new introduction to Incite! #19 (1991) remembers:

In this issue I wrestled with the reasonableness of continuing to publish a fanzine and run a record label while embarking on a career as a history professor at Harvard.

Alborn was also newly married. He sometimes described his life directly – travel to and from Britain; moving house; his father’s death; falling in love, engagement and marriage.

Most often, though, the life gets refracted through Alborn’s interests, musical and otherwise: it’s there in the columns of singles reviews, and in the letters about live shows, and in the brief manifestos. There are more informative, more typical, more intentional, more narratively transparent autobiographies than the one that Alborn’s fanzines provide, and there are autobiographies by people who proved more significant to the history of rock and roll, but right now there are none I’d rather read.

Comments