Emanations of Albion

Rosemary Hill · The London Stone

It seems that the usually irresistible force of Foster + Partners, architects, may have hit an immovable object in the form of the London Stone. Minerva, the developers who commissioned the Walbrook Building from Foster’s firm, have applied for permission to move the stone from its present location in Cannon Street in the City of London to a ‘purpose built display’ in their new complex, thereby getting it out of the way of the 35,000 square feet of ‘retail and restaurant accommodation’ they have planned for the ground floor. The case remains undecided but there are a number of significant objectors, including English Heritage and the Victorian Society.

This is not the first time the stone has been in the way. It was moved in 1742 when it was deemed a traffic hazard, again in 1798, for unspecified reasons, and once more in 1828 when it was set into the wall of Wren’s St Swithin’s church, where it should have been safe. But the church was hit in the Blitz and later demolished. The stone has been in its present location only since 1961. All of which might suggest that another removal wouldn’t matter much. Like Stonehenge, however, whose present concrete setting dates largely from 1964, the London Stone has a mythic traction that overrides dates and historical facts.

Nobody knows exactly what it is, apart from a piece of oolitic limestone, which suggests that it was brought to London in the Roman period. First recorded in a document dating from between 1098 and 1108, it has been variously described as a milestone, a pedestal and a monument. It is now a Grade II* ‘designated heritage asset’. Its original purpose was probably long forgotten by the time Jack Cade came to London in 1450 at the head of the Kentish rebellion and struck the stone with his sword to mark his claim to be ‘lord of the city’, giving it a symbolic association with resistance to corrupt authority.

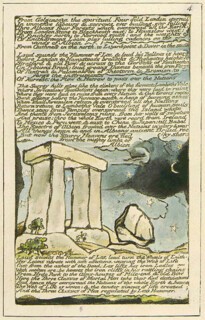

That myth was elaborated in 2 Henry VI. John Clark, writing about the stone legend, remarks that Shakespeare ‘has a lot to answer for’. William Blake probably has more. Blake, who saw history as ‘the field of recurrent attempts to wake up human conscience’, forged the connection between the London Stone and Stonehenge. In Jerusalem and Milton the two sites form corners of a triangle with Tyburn as places of ancient violence and imminent threat in the landscape of Albion.

Blake also introduced that bane of modern archaeology, the Druids, to the story. Half a century later, in 1862, a real druid, Morgan of Merioneth, published the hitherto unknown ‘ancient saying’ that if the stone were moved it would bring disaster on the City. The Victorian Society, which is involved because of the implications for the 19th-century ironwork round the stone, could just as well claim an interest on the basis that the legend itself is substantially Victorian. But that doesn’t mean it lacks power. Myths that are believed for long enough tend to break through into reality, as the Druids have, especially at moments when they strike a chord in popular feeling.

So the planning authorities are faced with a choice between historical fact and the power of association, commercial muscle and a long tradition of democratic protest. Maybe Blake’s emanations of Albion are manifesting in the Occupy protesters, waiting ‘upon the Thames and Medway... drawn through unbounded space’ to wreak vengeance on the City if the stone is moved. He would certainly have sympathised with them. In the present climate of opinion, and with the state of western capitalism in general, it might be wise to err on the side of caution and leave the stone alone.

Comments

The Conservatives would do well to consider all this as they sing "Jerusalem".

Transliterating the title, which was something like албион, it became "Albion".

Which is a pretty clever name for a newspaper about English Football.