At the Freud Museum

Christopher Turner

In 1952, Louise Bourgeois began an analysis with Henry Lowenfeld, visiting him four times a week at his apartment on Central Park West. She stayed with it, on and off, until Lowenfeld’s death in 1985. Lowenfeld had been a member of the rebellious Children’s Seminar in Berlin, run by Wilhelm Reich and Otto Fenichel, both of whom Freud dismissed as troublesome Bolsheviks (Lowenfeld’s father wrote a biography of Trotsky). But, in America, where he emigrated in 1938 – the same year Bourgeois did – he joined the New York Psychoanalytic Institute, a centre of orthodox Freudianism, and rejected his radical past.

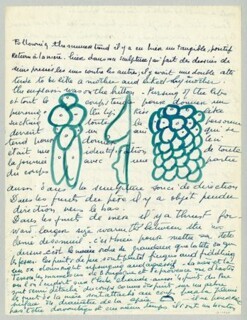

In 2007, before her retrospective at Tate Modern, Bourgeois’s assistant Jerry Gorovoy discovered two boxes of loose notes at her house in Chelsea; after she died in 2010 (aged 98), he discovered two more. These free associations or automatic writings are arranged in stacks and spirals like concrete poetry, and often relate to her analysis and the psychological conflicts that took her there. (The traumatic scene to which she returned over and over in her confessional work was the childhood discovery of her father’s affair with a much-admired English governess.) In an intriguing exhibition at the Freud Museum – the curator, Philip Larratt-Smith, compares the archive somewhat grandiosely to Van Gogh's letters – they are on show, in the inner sanctum of psychoanalysis, alongside a selection of her ragged, sexually charged sculptures and installations.

According to Bourgeois’s notes, Lowenfeld attributed the cause of her depression and agoraphobia to her disavowal of destructive impulses:

To Lowenfeld this

seems to be the

basic problem

it is my aggression

that I am afraid

of

Analysis freed her creative block and informed her art, but she often thought of breaking off her sessions. Her notes reveal her to have been an obsessive list maker – such as of ‘7 easy ways to end it all’ – and on one loose sheet (sold as a postcard in the Freud Museum shop for others battling with transference) she details her ambivalent relationship to analysis:

The analysis

is a job

is a trap

is a job

is a privilege

is a luxury

is a duty

is a duty towards myself

my parents

my husband

my children

is a shame

is a fare

is a love affair

is a rendez-vous

is a cat and mouse game

is an interment

is a joke

makes me powerless

makes me into a cop

is a bad dream

is my interest

is my field of study

is more than I can manage

makes me furious

is a bore

is a nuisance

is a pain in the neck

Her treatment failed to dissolve her Oedipal bind and fear of abandonment, but the trauma was the fuel that drove her work, which was an endless attempt to exorcise it. After Lowenfeld’s death, in a review of an exhibition of Freud’s antiquities for Artforum (she didn’t think much of ‘Freud’s toys’), Bourgeois wrote:

Freud did nothing for artists, or for the artist’s problem, the artist’s torment – to be an artist involves some suffering. That’s why artist’s repeat themselves – because they have no access to a cure. People sublimate and turn to art because, first of all, they would like to be sexual but they are afraid, and second, they feel guilty. In this day and age it is easy for people to be separated from sex. You certainly do not have to be religious to be afraid of sex. And the need of artists remains unsatisfied, as does their torment.

Comments

Only the deeply fucked up would seek such a deeply fucked up approach.

Crocodile Dundee got it right.

Didn't she have any mates?

"You can say that again," Dundee commented when shown some Jackson Pollocks in a Fosters advert.

Thus we think the thunk and when that fails get drunk.