ǝɔɐǝd ןɐnʇǝdɹǝd

Neve Gordon

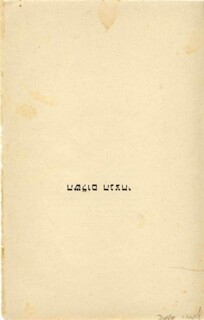

Last year I gave the Israeli artist Amir Nave an old Hebrew copy of Immanuel Kant’s Perpetual Peace, which I teach every so often in my Introduction to Political Theory class. He took the book, flipped through it, ripped out the title page, turned it upside down, signed it and returned it to me. Nave, an Arab Jew of Iraqi descent, didn’t say anything, but the gesture was eloquent enough: we are living in an era of perpetual war, and peace emerges, if at all, in the interregnum.

Nave’s children go to the same school as mine. It’s called Hagar, after the biblical figure who wandered between different peoples and cultures in the desert not far from where I live. Hagar was founded by a group of Jewish and Palestinian parents who wanted to create a shared space for their children. It’s the only non-segregated school in the Negev region, which is home to about 700,000 Israelis, more than a quarter of whom are Palestinian Bedouin.

A few years ago, after we had been running two Jewish-Palestinian nursery schools, the Beer-Sheva municipality allowed Hagar to make use of an old run-down school in a crumbling neighbourhood, one of the city’s poorest. The bathrooms stank: the decrepit pipes hadn’t been replaced for years. Outside, in the half hectare of yellow soil that the city bureaucrats called a playground, there was no water fountain for the children to drink from, not even any shade for them to play in. It was a site of callous neglect.

The library was in the bomb shelter. It had thick concrete walls, a low ceiling with long fluorescent lights, no windows and a heavy metal door. There were about two hundred books on old brown shelves along the walls. Nave, who was instrumental in transforming the school’s yard into a place of adventure and whose uncompromising vision has changed the way the school community relates to space, decided to convert the library into a pirate ship. He abandoned his Tel Aviv studio for a few weeks to build a deck, mast and wheel, turning the walls into the sea and the ceiling into a blue sky. He even imported a treasure chest and a statue of a pirate from England, who now sits gazing at the ocean. ‘Maybe the creation of a different space,’ he told me, ‘will be more inviting and allow the children to sail away.’

Boats appear in many of Nave’s paintings, and seem to symbolise for him the possibility of change. In My Ego and Me, the haunting but surprisingly un-despairing figures are foregrounded by an empty boat with four white oars. When I asked Nave about the recurring boat imagery in his work, he said: ‘It could be a flight fantasy, or the condition of possibility of creating something new, or maybe both.’

I am not sure if he has read Kant, or whether he is aware of the German philosopher’s search for the conditions that make knowledge, aesthetic judgment, moral behaviour or perpetual peace possible. But for me, Nave’s work evokes the possibility and the necessity of imagining differently in a war zone.