At the Wellcome Collection

Christopher Turner · Pickled Brains

I once met an aristocratic woman who had trepanned herself. In her moated Tudor manor outside Oxford, as an African Grey parrot nibbled her ear, she showed me the film she had made of the procedure. She shaved her hairline, bandaged her head, put on dark glasses and a floral shower cap, peeled back a patch of skin with a scalpel and applied the point of a dental drill to her frontal bone. A few minutes later its grinding teeth made it through the dura mater, releasing a geyser of blood. As it gurgled from the half-centimetre opening, she smiled, blood dribbling between her teeth.

Her DIY surgery, which created an opening similar to a baby’s fontanelle, was supposed to relieve the pressure on her brain, allowing the blood to pulse freely around her head to bring on a natural high. ‘It was rather like the tide coming in,’ she told me. ‘I felt a certain peace, it felt like a return, like I was rising in myself to a more natural level.’ She campaigned for parliament twice (in 1979 and 1983) on the sole platform that the operation should be free on the NHS. A decade ago, when the hole she’d drilled thirty years earlier had healed over, she had to go to Mexico to find a surgeon willing to create a new one, which he did with a hand drill.

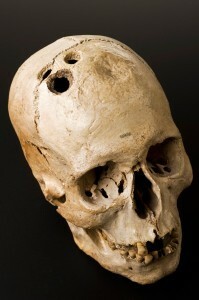

A brilliant and gory exhibition at the Wellcome Collection, Brains: The Mind as Matter, includes a section on trepanning (from the Greek trypanon, ‘borer’), the oldest known medical procedure. On display is a skull from Jericho dating from the Bronze Age, the cranium perforated three times like a bowling ball. The holes show signs of healing which indicate that the patient survived. In 1913, T. Wilson Parry experimented with oyster shells, shark’s teeth and obsidian knives to illustrate the ways our ancestors might have scraped away and prised out these coin-sized bits of bone. A cigar box of these primitive tools is on view, alongside later trephines, most of them variations on the corkscrew. These drills were used until the First World War to treat insanity, melancholia and migraines (to be replaced by the lobotomy, ECT and psychotropic drugs).

The curators, Marius Kwint and Lucy Shanahan, are interested in examining not ‘what the brain does to us’ but ‘what we do to brains’. They show how the brain – 1.4 kg of inscrutable tissue that Aristotle compared to a cold sponge (70 per cent is water) – has been measured and classified, mapped and modelled, cut and treated. ‘The perspective,’ Kwint writes in the catalogue, ‘stays for the most part firmly on the outside of [the brain’s] wrinkly surface.’

Philosophers looked to the brain as the seat of the soul, phrenologists divined character from bumps in the skull, and eugenicists used ‘headspanners’ to measure of intelligence. Anatomical museums and brain banks stored the craniums and grey matter of deviants and geniuses. A ‘skull of a prostitute who accompanied the army and was reputed to be cruel and violent’ is opposed to Raphael’s. The pickled brain of Edward Rulloff, ‘gentleman, scholar and murderer’, is on show next to that of an ‘educated, orderly person’, the suffragist Helen Garner. The members of the Cornell Brain Club, all ‘learned and eminent’, donated their brains to science, as did Charles Babbage. Einstein’s was stolen, and a small piece of it is exhibited here. There’d be no way to tell whose was whose if we didn’t already know.

The exhibition is not for the faint-hearted. But there are sublime moments too (a film by Daniel Margulies and Chris Sharp shows a fizzling MRI scan of someone reading Kant’s third Critique). There are brain slices stained vermilion to show the full glory of the tendrils of filigree; the ‘Brainbow’ mouse, its genetically coloured neurons a riot of fluorescent colour; and, perhaps most mesmerising, a ghostly, rotating 3D hologram of a bullet lodged in a brain (a synthesis of CT, MRI and ultrasound images).

Comments