Out of the Dark

Jon Day · The Tour de France

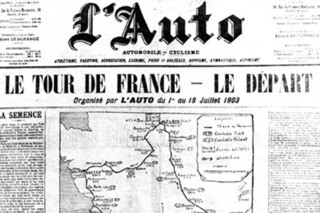

Bicycle road-racing has never been much of a spectator sport. Its origins lie in journalism, and the first great races, the Tour de France and the Giro d’Italia, were designed to be read about rather than watched. The yellow jersey worn by the leader of the Tour is the same colour as the pages of L’Auto, the newspaper that first organised the race. No one really knew what was going on out on the road during those early races. Cheating was rife and Géo Lefèvre, the only journalist to follow the first Tour from start to finish (the race was his idea), was described by his son standing at night ‘on the edge of the road, a storm lantern in his hand, searching in the shadows for riders who surged out of the dark from time to time, yelled their name and disappeared into the distance.’

Nowadays the peloton is followed by a vast caravan of vehicles. Support cars carry bidons of water and spare wheels, and wirelessly monitor riders’ vital statistics. TV vans and motorbikes zip around getting their shots, and the dreaded ‘broom wagon’ brings up the rear, sweeping up stragglers who won’t finish the course within the allotted time. Sometimes they get too close. On Sunday,during the ninth stage of the Tour, a car working for France TV collided with a group of breakaway riders, knocking Juan Antonio Flecha off his bike and sending Johnny Hoogerland into a barbed-wire fence. Both were back on their bikes in minutes, Hoogerland having his leg bandaged by a passing motorcyclist as he rode, but they are lucky to be alive.

It’s still difficult to know how best to watch the race. Fans who congregate along the route spend most of their time in dusty little bars, watching events unfold on television before rushing outside for a few minutes as the peloton whirrs by. More devoted disciples ride the route themselves during ‘l'étape duTour’. Still, a visit from the peloton can do wonders for a village’s tourist industry, and the waiting list to host a stage finish is years long.

It’s far easier (and perhaps more exciting) to follow the race online. As well as reading the live blogs and watching the video streams, you can traverse the terrain virtually, stage-by-stage, on Google maps. Another site lets you monitor a rider’s progress, speed, pedal cadence, heart rate and power output in real time – all a bit too intimate for my tastes.

This technologising of the body may help explain (along with the accidents) why so many riders die young. Professional cyclists, especially if they dope, sacrifice more than most athletes: their health, their ability to have children, sometimes even their lives.Fans want to know about training regimes and feeding schedules, VO2 max levels and blood profiles. It’s an extension of the geeky technology-fetish that prompts endless discussion about frame materials and gear ratios on cycling forums across the internet.

Comments

It's amazing that the riders take on so much pain, when you consider how little they earn in comparison to a footballer or a tennis player of modest achievements. It must be for the thrill of being there.