The Corporate Behemoth and the Insatiable Consumer

Thomas Jones

It has been suggested that to make sense of the recent riots we should put down our commentpapers and turn to our bookshelves. At the Economist, 'Bagehot' has been reading Hooligans: A History of Respectable Fears by Geoffrey Pearson (D.G. Wright reviewed it in the LRB in 1983). Slavoj Žižek looks to Hegel. But the book I've been brought back to most often over the last couple of weeks (at the urging of someone too young to know about the riots) is The Elephant and the Bad Baby by Elfrida Vipont, illustrated by Raymond Briggs.

Published in 1969, it tells the story of an Elephant who offers a ride to a Bad Baby. The Bad Baby – talk about giving a dog a bad name – says 'yes' and off they go, 'rumpeta, rumpeta, rumpeta, all down the road', helping themselves to whatever they fancy and being pursued by a growing number of shopkeepers. David Cameron would call it a case of criminality pure and simple. Easy to blame the parents, too: what's the Bad Baby doing out by himself? For that matter, what's the Elephant doing out by himself? Breaking the terms of their Asbos, no doubt.

But the book – on the nth rereading, anyway – seems to demand a denser allegorical interpretation. And the more I look at it, the harder it is to ignore the idea of the Elephant as symbolising the Corporate Behemoth and the Bad Baby the Insatiable Consumer, carelessly destroying together the livelihoods of small, old-fashioned high-street retailers, while the shopkeepers abandon their plundered premises and run off after them in a hopeless attempt to keep up.

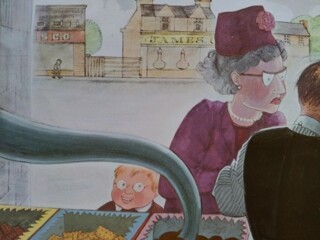

Eventually the Elephant sits down suddenly in the middle of the road and the shopkeepers go 'bump into a heap' – or, if you will, into recession. The Elephant has the audacity to blame the Bad Baby, and the shopkeepers join in pointing the finger. Then off they all go to the Bad Baby's house, where his mother – laissez-faire beyond the point of negligence during the good times – bails them out with 'pancakes for everyone'. Or that's what the text says: the picture tells a slightly different story, as we see the Elephant, whose fault it all really is, guzzling a large bucket of milk while everyone else at the kitchen table waits expectantly for the single pancake the Bad Baby's mother is tossing in the pan.

If this reading seems absurdly far-fetched, consider for a moment the authors' politics: Vipont was a Quaker; Briggs's other work includes When the Wind Blows, in which Jim and Hilda Bloggs fail to survive a nuclear holocaust, and The Tin-Pot Foreign General and the Old Iron Woman, a satire on the Falklands/Malvinas conflict.

Or, to get back to the book in question, there's the snack bar from which the Elephant pilfers a couple of bags of crisps. A man on a ladder is painting over the old shop sign, '...'s Fried Fish', and a poster in the window announces: 'As from Mon 1st Sept These Premises will open as "Sam's Super Snacks" – a comment perhaps on the decline of the British fishing industry as well as the Americanisation of British consumption habits. The notice also confirms that the story is set when it was written: in 1969, 1 September fell on a Monday.

Finally, take another look through the window of the grocer's shop. There, unobtrusively in the background, creeping in, like the elephant's trunk, from the left-hand edge of the page, is a branch of Tesco.

Comments

-

19 August 2011

at

4:36pm

SamC

says:

Yes. But how does the Elephant shift the blame on to the Bad Baby? By dodging the issue and saying that he "never once said please", which seems to shock the shopkeepers even more than the loss of their merchandise, strangely. I'm not sure that the even the corporate behemoths are that slippery.

-

19 August 2011

at

6:28pm

A.J.P. Crown

says:

'ESCO is from "BAD BABY, ALFRESCO", a scatological euphemism. Used as the name of the shop, the phrase implies that consumer goods are "total shit", and this is confirmed by the question posed at the bottom, "Would you like a chocolate biscuit?" (Do you want more of this shit?). "No, thank you!" the woman seems to say. Her head partly obscures the name Jamie Oliver on the adjoining shop, anticipating his call for locally-grown produce.

-

19 August 2011

at

6:56pm

Bob Beck

says:

@

A.J.P. Crown

Or, in the alternative, the biscuits stand in for persons of a darker skin tone, whom she's deliberately and perhaps angrily refusing to take notice of. An instance of xenophobia, or indeed racism?

-

19 August 2011

at

9:34pm

echothx

says:

This is my 2 year old son's favourite book. He wasn't impressed with my retelling this evening with this narrative. However he has noticed that the baby looks terrified when the elephant first picks him up. In the scene when the elephent dumps the baby on the floor the elephant and shopkeepers do not cry 'thief!'say "But you didn't once say please!" My son hasn't learned the complexities of social etiquette, yet already knows that if he wants to help himself to daddy's cake, saying 'please' isn't going to make the slightest bit of differnence, nor will Daddy (like the riot commentariat) complain about the loss of moral standards when he fails to do so.

-

19 August 2011

at

11:06pm

Bob Beck

says:

By the way, the book could as easily be prophetic as contemporary. After 1969, the next year in which Sept. 1 fell on a Monday was 1975. Margaret Thatcher -- friendly in principle to both the Elephant and the Bad Baby, surely? -- became leader of the Consevative Party in... 1975. (In fact she formally took over in September, if I understand right, though first elected to the position in February).

-

20 August 2011

at

12:38pm

Geoff Roberts

says:

Good article by Bagehot. I lend my copy of 'Hooligans' to anybody who starts moaning about the decline of morals, the failure of schools, the dangers of alcohol/cannabis, the threat of TV to our standards and so forth. The Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, once the hammer of the left and the upholder of all that is honourable in society is having DOUBTS about Capitalism this week - not surprising really. One of the Editors, a gentleman called Frank Schirrmacher, is beginning to wonder of the left actually got it right with their analysis of capitalism, and today, there is a study of the causes of the present impasse by two sociologists, who doubt if the politicians can find a way to regulate the financial markets to avoid any further catastrophes.

Read moreI'm just saying.