At White Cube Mason’s Yard

Jonathan Romney · ‘The Clock’

When the Lumière brothers filmed workers leaving a factory in 1895, one assumes their subjects were clocking off at 5 p.m. – but it would be nice to know for sure. If the Lumières had thought to include a timepiece somewhere in the frame, Christian Marclay could have used it in his new video work The Clock(showing till 13 November at White Cube Mason’s Yard).

Marclay has taken thousands of fragments of footage containing images of clocks, watches and other timepieces, and edited them into a 24-hour collage (the gallery is normally open only in the daytime, but the installation can be seen at weekends in its round-the-clock entirety). The time references on screen are synchronised with the real time of projection, so that if you walk into the gallery at 5.47 p.m., say, the clock or watch on screen will read 5.47. That is, the film itself functions very accurately as a clock.

Quite apart from the residues of narrative that flash past, Marclay is specifically inviting viewers to watch the minutes and hours pass. I walked in at 2.40 p.m. and sat on a sofa. An hour and a half later, I was still watching. Once hooked, you watch mesmerised, unaware of time passing – and yet, at the same time, aware of little but the flow of minutes.

It’s frightening to imagine just how many films – famous, forgotten, good, bad and drearily indifferent – Marclay and his researchers must have watched to cull all these fragments. The only criterion for selection is that the clips should contain overt references to the time of day. So the images are drained of all meaning other than temporal – and yet, once Marclay splices his extracts together, new meanings emerge, some immediately comic. The key gag that runs throughout The Clock is that, while times of day are of primary importance, all other temporal considerations are cast aside: each image exists in the here and now. A duel starts in a James Bond film and ends in a Sergio Leone Western. Romola Garai, driving a car in Glorious 39 (set in the 1930s, made in 2009) is chased by Burt Reynolds in the 1970s. Edward G. Robinson and a young man in blue scrubs climb staircases simultaneously – at 3.40 p.m., but in different decades.

Marclay and the sound designer Quentin Chiappetta play sonic tricks too. A train chugging past a window in Stockholm is heard speeding past Dirk Bogarde and Julie Christie in 1960s London. Theclanking sound summoning Ed Asner in an American clip is made by a young man banging a watch on the rails of a Taipei walkway (the Taiwanese film is What Time Is It There?, Tsai Ming-liang’s contemplation of the existential problems caused by time zones).

Overall, we seem to be watching a huge, madly diffuse multi-stranded narrative with a cast of thousands – an epic drama about simultaneity, in which no narrative can ever reach completion.Micro-narratives emerge, not always linear. One is the story of a man bound and gagged, forever sweating nervously as he contemplates a time bomb. Another follows Jack Nicholson’s ageing process,from young rake (whose singing in Ken Russell’s Tommy apparently adds to the torment of the time bomb victim) to the haggard doyen watching the clock in About Schmidt (2002).

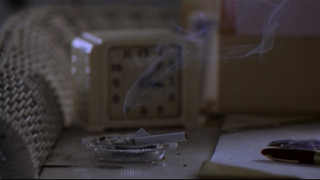

Marclay’s collage teaches us things we might have overlooked about times of the day. Between three and four in the afternoon is a period for slumber: alcoholic screenwriters and maverick cops wake around now, while others start dozing at their desks. Some screen characters live to their own clock anyway: Jack and Meg White, in Jim Jarmusch’s Coffee and Cigarettes, lounge in a café at 3.30 p.m. and make it look like the small hours. Identifying the time in certain scenes gives them a whole new slant: what I had always assumed was a breakfast scene in Raging Bull turns out to be set at 2.50 p.m.

Timepieces can date a film as precisely, or as damagingly, as clothes: little now looks as passé as a once-snazzy chunk of digital hardware on the wrist of an 1980s action hero. All sorts of watches are on show here: half-hunters for Western gamblers, a fuck-off flashy number with three dials for Jason Statham, and for John Lithgow in Brian De Palma’s Blow Out, a fake wristwatch that’s handy for garroting. Watching The Clock, you also come to realise that wristwatches measure personal time, linked to the secret hopes and plans of individuals, while clocks embody merciless, impersonal, official time. Big Ben appears often, a guarantor of accurate time in the real world. (When do city clocks go wrong? When Harold Lloyd is dangling from their hands.)

Marclay’s piece has parallels with the collage films of Gustav Deutsch, and as an exercise in temporal monumentalism, The Clock inevitably makes you think of Douglas Gordon’s 24-Hour Psycho (although Marclay’s piece is far more entertaining). You are reminded too of Jean-Luc Godard’s similarly voracious sampling project, Histoire(s) du cinéma. But where Godard looks to clips for their specific cultural, historical or even emotional resonance, Marclay chooses his extracts simply because that they mark the time of day. Godard is always thinking of history; Marclay thinks of 12.46 or 5.53. Film-making may be an inexact science, but here Marclay has turned cinema into a precision timepiece. His extraordinary achievement is philosophical, elegant, hypnotic, frequently hilarious. And you can set your watch by it.

Comments

Perhaps this is not so surprising...recall that, when describing how cinema is the art of sculpting in time, Tarkovsky points to the pressure of time in the shot - it is within the shot that we experience time in cinema, rather than in the montage of an Eisenstein or, evidently, a Marclay.

Similarly, if the experience of time's passing is what Bergson called durée, in contrast with that spatialised phenomenon which lends itself so admirably to the counting of clocks, of physicists, and of all those who urge us to become more time-efficient, then it is no surprise that the experience of time's passing slips away as time is counted on screen.

An enjoyably contrary endeavour for a film-maker...